Google dataset search - a reflection on the implications

It has been a very eventful couple of weeks in the academic, publisher and library related worlds with regards to the push towards open.

First my Twitter feeds was buzzing about Plan S. Described as "radical" by Nature, this brings together 11 research funders in Europe with a mandate to make all papers free to access immediately without embargo with a open license (preferably CC-BY). This according to this analysis would disqualify authors from publishing in 85% of journals!

I lack any special insight or expertise in this matter , though I recommend reading takes by respected voices like Peter Suber and Jon Tennant

Secondly the Workshop on Open Citations was held last week in Italy. It brough together a diverse group of people working on Open Citations. Representatives from OpenCitations , Wikicite, Crossref, datacite, EuropePMC, libraries (Linked Open Citation Database (LOC-DB) ) and more came together to talk about the progress and their work in both making citations open and using such citations. I haven't had the time to look through everything, but what I glimpsed on Twitter looks really exciting and I'm looking forward to going through the material.

Though I suspect awareness of the open citations movement is much less widespread than that for open access (articles) and open data , this is I believe a important area that libraries should be watching.

Totally agree with Anne Lauscher’s talk: libraries should be playing an a leading role in curating open citation data. But globally-speaking, are they? How can we get more librarians doing this? #wooc2018

— R⓪ss Mounce (@rmounce) September 3, 2018

This in my view can be considered a new and relatively lesser known part of Lorcan Dempsey's "inside-out" work that libraries should be doing.

As a sidenote : As I write this - Applications to attend WikiCite 2018 in Berkeley, California in November is still open. Applications close on Sept 17, 2018. Travel funding is available for selected applicants, so this might be a option to consider for those who have an interest and have something to contribute but lack funding.

Google Dataset search

Lastly, the piece of news that probably made the most splash on the radar of many was the news that Google launched a dataset search engine called Google Dataset Search.

How big was it? I was talking to a faculty the day it was launched and he heard of it!

Described by Google themselves as "Similar to how Google Scholar works, Dataset Search lets you find datasets wherever they’re hosted, whether it’s a publisher's site, a digital library, or an author's personal web page. "

Most articles on the Google Dataset search follow this lead and describe it has "like Google Scholar but for datasets" and indeed in most ways this is apt. This search like Google Scholar will act as an aggregator but will not store the dataset itself unlike say models by ResearchGate and Academic.edu (though they collect and store papers and not datasets as of yet).

How Unique is Google dataset search?

In a sense this move by Google isn't surprising. As I noted just last month, general dataset discovery is a "new" library challenge. As I noted then aggregation and discovery of datasets is in it's infancy. Still it's surprising that until now there was no major attempt to do a "Google Scholar but for datasets" from anyone.

Here's my list of closest alternatives.

While global Aggregators like BASE and CORE do aggregate repositories and do crawl/harvest and index subject and institutional repositories which includes some datasets, their primary focus is not on datasets but on articles. Their general targets for crawling also means they will miss out datasets not solved on traditional repositories like those from data.gov.uk.

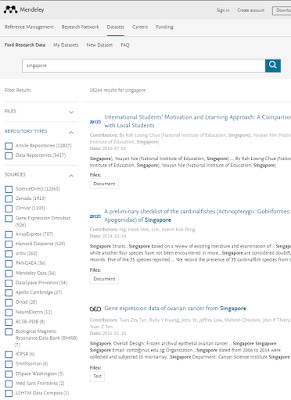

As noted in the Aug blog post, Mendeley Data can be seen to be a early innovator here, not only does it aggregate different repositories (both article and data) like Zenodo, Dryad, Dataverse, certain Dspace installs and more, it also includes whatever data such as tables or figures it can from Sciencedirect articles.

However as note worthy this aggregation is, a glaring omission is it's main competitor Figshare. Even if Mendeley data was to add competitors, the fact that Elsevier which owns Mendeley is not a neutral party, makes it a non-starter really.

Clarivate (formerly Thompsons reuters), markets themselves as Publisher neutural (a shot at Elsevier perhaps) and they have had a Data Citation Index for years. I'm unsure of the take-up subscription rate, but my understanding is they only index selected data repositories that meet certain criteria.

I wonder if the idea is to replicate the idea of Web of Science, just as Web of Science only includes prestigious journals, this Data Citation index aims to only include "prestigious repositories" whatever that means.

Leaving aside the fact I'm not sure if the model for journal papers, work well when transfered over to Datasets (beyond certain STEM repositories, I don't think there is as strong branding and control for data repositories as for journals), clearly Clarivate's Data Citation index isn't going to be the answer. We need a broader more expansive and hopefully free or low cost data search engine.

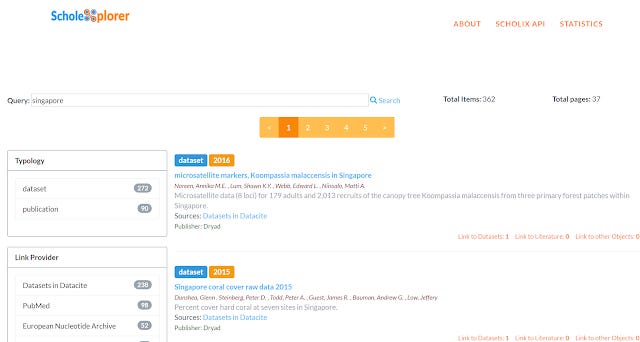

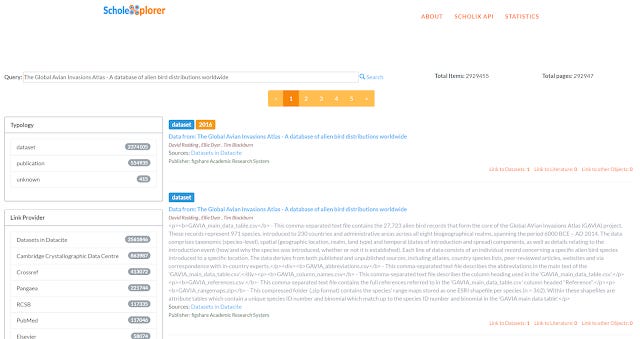

Scholexplorer - OpenAire's Scholix hub is also another interesting data search, though as I understand it the main focus of this is linking article literature or dataset to dataset.

In other words, this cannot find datasets that have not being linked/cited from other articles or datasets.

Lastly there is the re3data.org (Registry of Research Data repositories) which is the data repository version of OpenDOAR (Directory of Open Access Repositories) and ROAR (Registry of Open Access Repositories)

The main problem is these tools are designed to search for suitable data repositories not for the contents themselves.

So as we can see Google Dataset search is a unique offering so far that promises to allow you to search across all datasets regardless of which repository or subject it is in. But as you will see later, this is a very ambitious undertaking (far more than just aggregating papers) and there are doubters who feel Google is unlikely to succeed.

Google datasearch feels raw even for a "beta" product

It is very very early to really judge Google Dataset search now as it is labelled as beta. But let me give some first impressions while kicking the tyres.

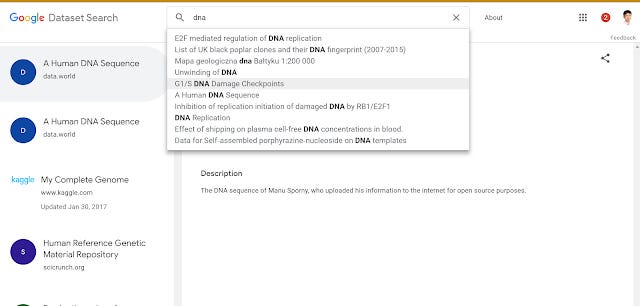

Google's UI style is well known (limited filters and facets, less focus on advanced search) but current the dataset search is barebones even by their standards.

You get a nice auto-complete but as it stands a very basic function is missing.

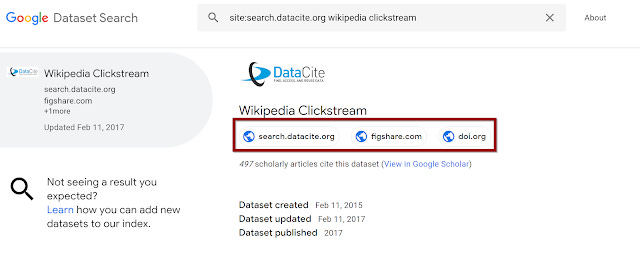

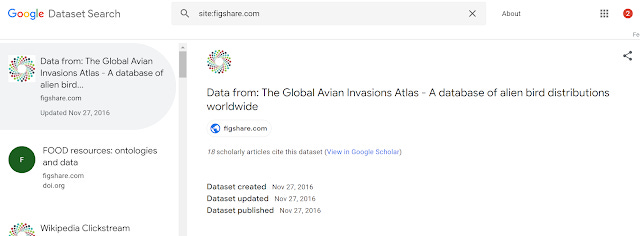

I was trying to check if every dataset on a data repository was included in the search by doing a site:Domainname search but the number of results for each search is missing! Not sure why this was left out as it makes trying to determine if all records are included much harder. (Or perhaps that is the point, you are not supposed to do that until the total number of results feature is added).

For searching syntax wise, the obvious assumption is what works for Google or perhaps Google Scholar would work but that would not be a safe assumption though the site command seemingly works.

But then again it doesn't quite work for Google Scholar or not the way you expect because Scholar only shows a record using the site command if it's is the primary record. Which also makes me wonder how will it handle identicial or similar datasets from different sites?

In the example above, we see that this dataset exists in 3 locations. Doing a site:search of all 3 domains bring up the dataset, so at least from this example, it seems safe to use site command to count datasets included per domain....

Technical note, There are "SameAs" properties for source and provenance that can be set using Schema.org (see later), I'm unsure if this is what is happening here.

It would be nice to have the search syntax to search by date, or by filetype (e.g. csv, sas etc). At the very least the Google equalvant for the later doesn't seem to work.

In any case, it's probably pointless to try to figure out what works for searching when everything is so raw.'

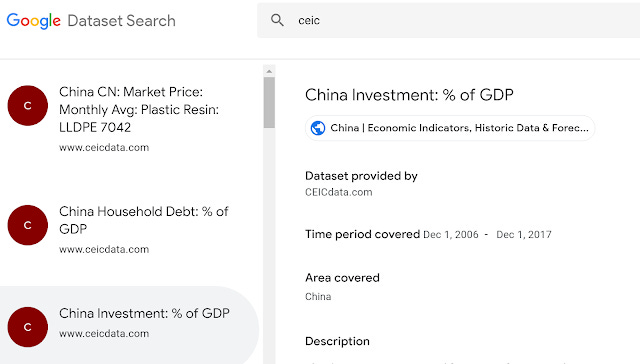

In terms of coverage, it's hard to do a comprehensive comparison, but I do notice that not just open data can appear. For example closed/properitary data from CEIC is findable too! There is no link though. This makes me wonder will it also surface closed datasets that have metadata in Schema.org? I would guess yes?

You also can find datasets from data.gov.uk, Kaggle, besides the usual Figshare, Zenodo etc.

Citation counts in Google dataset search

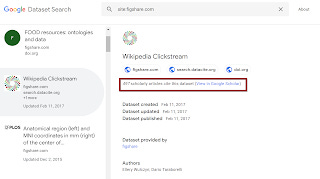

The main thing that caught my eye was that Google Dataset search lists cites per dataset! Obviously if data sharing is only to take off, being able to show a reliable data citation count is paramount.

The main problem is it's unclear to me how Google is doing the data citation counts.

Take this dataset on Figshare, Google shows 18 articles citing it.

Clicking on the link though just brings you to a simple string search where you get 2 articles.

Looking at the altmetrics on the Figshare dataset page itself you see 3 citations which is close to what the string search shows.

Lastly looking at Scholexplorer, I see this very dataset has 2 citations but from datasets not articles.

Either way , Google data search is showing a massive difference, an increase from a couple of cites to 18! The temptation for many is to shrug and say, this is expected. After all Google Scholar shows more cites than most citation databases because it has the broadest universe of items, so it's no wonder datasets have the same behavior. But is that really so?

How does Google Dataset search actually work?

By now, we have a general if not exact idea of how Google Scholar works. Does Google Dataset seach work the same way?

Yes and No.

Like Google Scholar, the dataset searcher crawls the web for content to index. But unlike Google Scholar, metadata is critical for the dataset content to appear!

Datacite who seems to be a major partner of this initative states on their blog two main requirements for datasets to appear in the search.

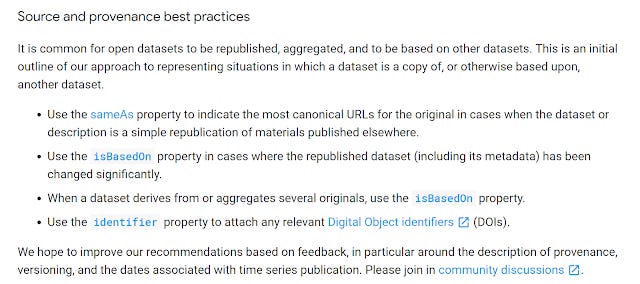

Firstly, you need schema.org metadata to be embedded into the dataset landing page so that the Google indexer can find them, and secondly the data repository needs to provide a sitemaps file with the URLs of all dataset landing pages.

As the Google blog post states, "A search tool like this one is only as good as the metadata that data publishers are willing to provide".

I personally find this somewhat "ungoogle" like, Don't get me wrong Google and Google Scholar cares about metadata but they are also most famed for their ability to auto extract and recognise content from pdfs and webpages with varying degree of success. In the early days of Google books and Google Scholar, it was easy game for researchers to write papers exposing how much junk metadata was in these products due to such auto-extraction methods and even today a rallying cry against Google Scholar for many librarians is "We don't know what is in there and everything is automatically extracted and or there is a lot of rubbish metadata in there"

So yes I find it somewhat ironic and as you see later I'm not the only one to think so. Then again this is datasets we are talking about and not text. Journal articles generally have the same structure particularly in PDF and can be easily recognised and metadata extracted . not so with datasets as noted in the nature article "Although the system might become more sophisticated in the future, Google currently has no plans to actually read the data or analyse them, as it does with web pages or images. " . That said this Googler claims that "we are already getting inside datasets via (rather tentative/exploratory) csvw-based markup" though it would still be embeded metadata only this time in the dataset itself.

Given this understanding that Google is relying on schema.org metadata , I confess I still don't understand how it detects cites to datasets. Surely there aren't that many articles or datasets flowing around with schema.org using the citation property?

Implications for libraries for data repositories

The first obvious implication for libraries is to ensure the datasets they host in their repositories are visible in Google dataset search. Given the name recognition Google and Scholar have with faculty, I predict a very common strategy would be for librarians to show faculty that their datasets deposited appear in the Google Data-set search.

As noted above the main requirement is that Schema.org metadata is embeded into your data repository pages. Incidentally I was asking about requirements for data repositories a few weeks ago.

A Data Citation Roadmap for Scholarly Data Repositories https://t.co/o2lQkoNclB . Curious how well do data repositories like @figshare @dataverseorg @tind_io @Mendeley_Data, @datadryad, @ZENODO_ORG, Dspace etc match up to these requirements? Anyone done an analysis? pic.twitter.com/CTzwbHUvz8

— Aaron Tay (@aarontay) August 10, 2018

You can read the tweet to see replies form the various data repository providers but it sure looks to me "recommended" Guideline #7 - "The machine readable metadata should use schema.org markup in JSON-LD" is becoming very important.

Unfortunately while many data repositories like Figshare, Dyrad. Dataverse, MendeleyData have support of Schema.org (see list here) , many more do not.

In particular, I suspect many institutions using open source data repositories like Dspace, eprints will need to do some extra work to add in this feature with a plugin (if it exists) , or code up something to handle this.

Native support = No. But if they are using Datacite (as most are) then indirectly they are!

— George Macgregor (@g3om4c) September 6, 2018

But I have no doubt with this move by Google, a lot more repositories will start prioritizing this.

Unfortunately, Google's new dataset search doesn't index @OSFramework yet – they'll have to supply JSON-LD metadata or allow users to do so. @figshare

and co show up. https://t.co/ScombCZVzm— Ruben C. Arslan (@rubenarslan) September 6, 2018

Particularly since evidence is starting to appear this might increase discoverability

Google Dataset Search having an immediate impact on the discoverability of data supporting published academic articles - Here's the first few days for @PLOS pic.twitter.com/bWLCQG0Jyk

— figshare (@figshare) September 10, 2018

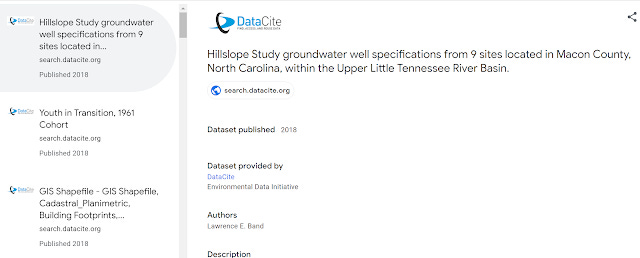

What if you have a data repository but do not have the capable to add Schema.org to the landing pages? Are you totally invisible? Not quite. Chances are you registered your dataset with a Datacite doi and Datacite has done some work to ensure their datacite entry is indexed in Google.

As datacite.org states " If a data repository doesn’t provide schema.org metadata via the dataset landing page, the next best option is indexers that store metadata about the dataset. DataCite Search is such a place, and in early 2017 we started to embed schema.org metadata in DataCite Search pages for individual DOIs, and we generated a sitemaps file (or rather files) for the over 10 million DOIs we have."

Here's an example of what this means.

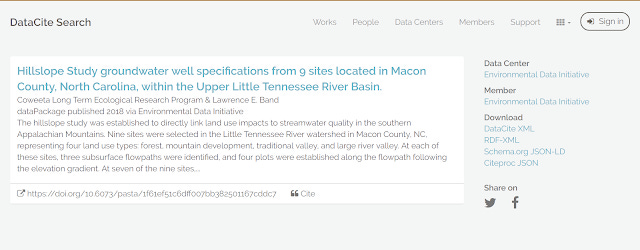

Take this dataset "Hillslope Study groundwater well specifications from 9 sites located in Macon County, North Carolina, within the Upper Little Tennessee River Basin.". It does not have Schema.org embeddded on the landing page.

All is not lost though. It is registered with a datacite.org and you can find a datacite record at search.datacite.org.

Looking at the page source, you can see this record page has Schema.org tags and is hence visible and eligible to be indexed by Google dataset search and as such it appears in the search.

In effect, even if your data repository is invisible to the search, datacite will ensure their record is indexable and hence a searcher can find their way to your repository via that record at the cost of an additional click.

The technical details can be very complicated (see for example this case) but this gives you a taste of how it works.

Citations in Google dataset search revisited

My original idea was that while being indexed in the search relied on crawling of Schema.org metadata , citations from journal articles were based on some smart parsing of citations in text articles (which they have tons of) to detect cites to datasets.

But given Google's focus on schema.org metadata for this product could this "X scholarly articles cite this dataset" be also from Schema.org metadata? It could be possible given that there is a citation property for articles and datasets. I highly doubt it, since the amount of citations in articles or datasets marked with schema.org should be close to nothing.

All in all I have no clue how citations are obtained in Google dataset search,

Will Google succeed?

I'm not the only one who notes the irony of Google calling for good metadata and going further into saying it is almost impossible to get researchers to do structured metadata.

I’m gonna enjoy watching Google try to get scientists to use structured metadata.

Reeeeeeeeally gonna enjoy this. Kicking back with some popcorn, you betcha.

(I give the data search five years to live, give or take one. That’s about how long it takes Google to get bored.)— Ondatra iSchoolicus; @libskrat@mastodon.social (@LibSkrat) September 6, 2018

The above person goes on to say that s/he is willing to bet that Google will give up this dataset search in 5 years.

On one hand, I suspect the person underestimates the influence of Google. Every new faculty I've met in the last 3 years have setup and maintain their own Profile in Google Scholar without prompting from librarian.

Not to mention the good brand name built-up thanks to Google Scholar will automatically confer some credibility to the dataset search which will logically mean researchers want their datasets to show up there.

I can see researchers persuaded to do this, particularly if libraries make it easier to enter very simple metadata (UX!) that is converted to Schema.org. After all look at Researchgate, plenty of faculty deposited their own articles with very little incentive and pretty much no brand name at the time.

Google may or may not get bored and give up, but I do expect that even if it becomes a standard to provide metadata va schema.org, the quality will be minimal. You would get title, author, license maybe funder but nothing much else.

That said, in a world where datasets have minimal metadata and with everything indexed in one search, one wonders the effectiveness of a one data search to rule them all approach. Unlike articles where poor metadata can be made up somewhat with indexing of full-text with datasets Google any sort of magic sans metadata is likely to be limited and Google must rely almost wholly on metadata and poor limited metadata is likely what they are going to get.

This leads to a situation where you search a large pool of items, with poor limited metadata. If so relevancy is going to struggle , so I wonder if a subject specific data search is going to predominant. This echos the web scale discovery vs subject databases fight.

To be fair, Google themselves are aware of the difficulties

Should we hope for Google dataset to succeed? Worries about open infrastructure

Google Scholar is beloved by many , including me. It is a free yet excellent tool. Assuming Google dataset search grow to the same level and should we cheer it on to succeed?

There are many who don't think so. Take this tweet

So, @Google is building a search engine for research data.

Yet another proprietary index on top of our data that nobody can reuse & another inferior list-based interface pushed onto scientists by Google's market dominance.

This is detrimental to science! #DontLeaveItToGoogle pic.twitter.com/EG2b9dHnlU— Peter Kraker (@PeterKraker) September 10, 2018

Using the #DontLeaveItToGoogle hash tag , Peter talks about the importance of not letting Google a commerical company dominate and to push for Open source infrastructure.

In particular, the fear is that this tool will be similar to Google Scholar which lacks a API, which leads to data being stuck in a silo.

For those who don't know -- Google provides open APIs for some of its products, but not for Google Scholar and not for Google Dataset Search. Furthermore, at least for Google Scholar, they've said they never will. #DontLeaveItToGoogle

— Heather Piwowar (@researchremix) September 10, 2018

That said, one suspicion fort the lack of APIs in Google Scholar is beause of a conditon set by journal publishers in return for allowing the Google crawler to crawl their full text. But with datasets this might not be a barrier, as the Nature article notes APIs might be added in the future, but you never know.

Still even with an API, I don't think it goes all the way as compared to having truly open infrastructure. For example even with a API , Google could still shutter the service.

That said, I personally think Google is playing as fair as it could under the circumstances. They are using schema.org, a open standard and nothing prevents others from crawling the web and using the standard to index datasets.

Realistically speaking of course Google has more experience in crawling and indexing the web, and their clout means what they "recommend" will be taken seriously and this move has clearly given legitimacy to the push towards data discovery.

Still leaving Google dataset search as the one and only comprehensive dataset search is dangerous, Google is a commerical company and could at any time shutter the service. There has been recent talk about the need for open infrastructure on top of open data and open access and clearly the same holds for dataset search tools.

Conclusion

All in all , I believe this move by Google will be a big step in making the importance of data discovery front and centre in the eyes of many. In many ways, this new discovery challenge might mirror developments for article discovery unless we are careful. Will we be wise enough to learn from history?