Some more reflections for OA week 2021 - Open Knowledge = Open metadata and Open full-text

It seems like OA week first started as "OA day" in 2007, the year I became a academic librarian. Since then for the next 14 years, I would mark OA week, with an invited talk or two, a blog post or more commonly nothing at all.

However my understanding of Open Access, Open Data expands every year and so it seems does the scope of OA week, with this year's theme being “It Matters How We Open Knowledge: Building Structural Equity” which aligns with the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science.

This year I gave a talk at COAR Asia OA meeting on the somewhat grand title of "Cashing the Cheque of OpenAccess Movement: Emerging Tools Built on Open Access Data " (with thanks to this blog post). I won't link to the talk, as it's pretty run of the mill about how coming of open full-text might change everything, but as always while preparing for the talk, it helped sharpened my thinking on these issues..

Here are some "insights", or thoughts I had while preparing for the talk

1. Open Knowledge = Open metadata and Open full-text

One of the things that surprised me joining The Initiative for Open Abstracts (I4OA) was the realization that there were some Open Access Advocates who while not outright hostile to the camp pushing for Open Scholarly Metadata, still felt that such initatives was a distraction at best. After all I think the reasoning went let's just push for open full-text and once we have that, we can extract the metadata?

I personally also wasn't sure that my proposed talk this year at the COAR Asia OA meeting would be welcomed because while it was supposedly about the possibility of text mining of full text, I realized a lot of the example of new emerging tools I was thinking of actually only came about because of the availability of open scholarly metadata rather than open full text!

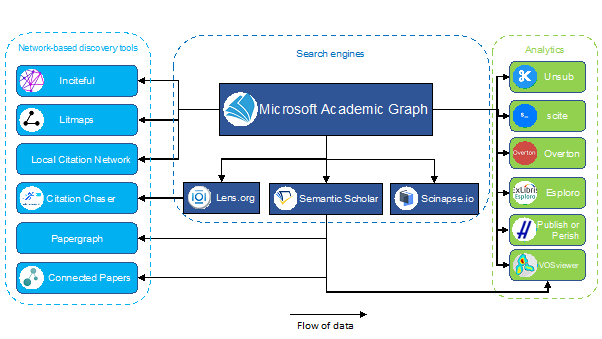

Take my favourite class of tools that I like to call citation-based literature mapping services like ResearchRabbit, ConnectedPapers etc. These sets of tools only started appearing very recently because they could draw on the availability of fairly comprehensive scholarly metadata (e.g Microsoft Academic Graph, Crossref, Semantic Scholar etc).

Citation-based literature mapping services based on open metadata

Same goes for the sudden emergence of many cross disciplinary discovery citation indexes (e.g. Lens.org, Scilit, Scinapse and even Dimensions is built on top of Crossref open data), Science mapping tools like VOSviewer, Citespace can now provide more inclusive analysis by using more diverse citation data (via MAG, Crossref, Lens.org) than what is in traditional indexes like Web of Science.

See coverage of new citation indexes

Sure I could think of examples that draw on full-text to do their work , particularly the rise of citation sentiment/contexts classifications seen in scite, Semantic Scholar and apparently even Clarivate's Web of Science has a limited beta on "Enhanced Cited Reference classifed by use" . I also suppose the work of startups like Scholarcy and UNSILO with expertise in doing NLP of academic text would benefit from the rise of open full text, but it seemed to me a lot more examples currently draw from either open Scholarly metadata, or both, then just on open full text.

Then two things struck me.

Firstly, Open Knowledge should be both open scholarly metadata and open full text.

Sure, you could in theory extract much scholarly metadata like title, abstract, author from full text but do you really want to do it if you can avoid it? Clearly, if you could get access to nicely human curated metadata that is open for reuse, that would be far easier than dealing with messy unstructured text.

There is technically different types of metadata, while some metadata types like descriptive metadata can probably be extracted using text mining, other types of metadata like administrative metadata and external structural metadata may not be 'derivable' via text mining of the item.

Of course sometimes, you have no choice but to text mine. For example I was recently reading OpenCitations' David Shotton's piece entitled "Academia’s missing references" which talked about where we could go from here given that the Initative for Open Citations (I4OC) had been amazingly successful in opening up the vast majority of records with references deposited in Crossref (almost 90%, a major hold out is IEEE).

For one thing the fact almost all records in Crossref with references are open, doesn't prelude the possibility that many records in Crossref are missing references (>50% records do not have any references deposited) where publishers (particularly smaller ones) simply choose not or are not capable to submit references to Crossref.

... as (per June 2021) 53% of DOIs did not have references in Crossref at all - either because these were not deposited, or because they don't have references at all (this is a challenge to separate out)... 2/n pic.twitter.com/ga82eBOCCB

— Bianca Kramer (@MsPhelps) September 10, 2021

And even if this was not an issue (it's unclear how many of the Crossref records with no references really have any references e.g. front material), there is also a need to handle non-crossref sources and targets. For example this would mean extracting reference lists from journal pages that did not contribute to Crossref or from pdfs of books with references (with no Crossref dois) and including non-crossref sources.

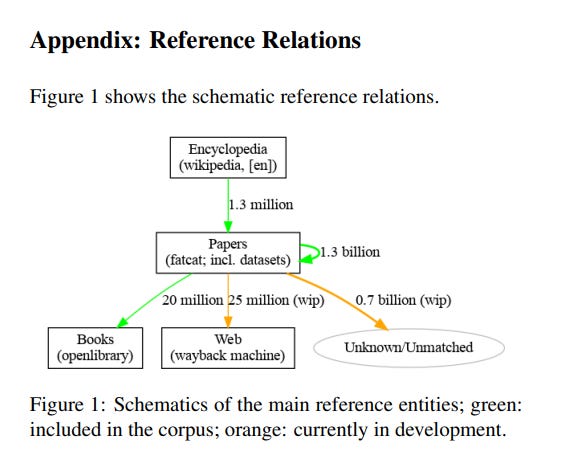

And indeed as luck would have it, the next piece I read days later was Refcat: The Internet Archive Scholar Citation Graph which described the latest open citation graph from the Internet Archive.

Their analysis suggests that out of 1.3 billion citations in Refcat, over 1 billion are in COCI, the OpenCitations Index of Crossref open DOI-to-DOI citations, suggesting that the bulk of references are in the traditional Crossref Doi to Doi set. Still why is there an additional 0.3 billion citations in Refcat?

Part of it I think is while COCI only handles Crossef doi to dois, Refcat will include other PIDs (Datacite DOIs or PMIDs). Also more interestingly it also handles citations to books (via Open Library ) and to webpages (via wayback machine). Lastly they include cites from Wikipedia English.

Refcat: The Internet Archive Scholar Citation Graph

Secondly what stuck me was this. I had this conception that Scholarly metadata had to be human curated and would forever be independent and seperate from open full text.

This was silly if you realize a lot of the publicly available Scholarly metadata? They are fruits of text mining of full-text.

From BMJ publisher hiring Scholarcy to use text mining to extract references from their back files PDF to deposit references into Crossref to support I4OC , to services and tools using meta-data from Microsoft Academic Graph, these are all fruits of text mining from full-text. These are just some of many examples, where we use and consume open Scholarly metadata where part or whole of it comes from text mining.

It seems to me that even if we lived in a 100% OA world, there would still be demand and a need for organizations to either release good open metadata to free up the need to do unnecessary text mining and failing that for organizations to extract such metadata using text mining and making it freely available with an open license to speed up innovation.

I suspect in such a world, there would be as many if not more tools and services relying on secondary metadata extracted and other structured data extracted and derived from open full-text then those that mined data directly as that would be a huge undertaking that fewer organizations could do.

2. Microsoft Academic , CORD-19 provide a glimpse into the future of what might be

Once I came around to this thinking, I realized all the new emerging tools I was seeing? They are all fruits of mining of full text and for example Microsoft Academic Graph was showing us a limited glimpse of the future where open access full-text was mostly fully available.

After all what is Microsoft Academic but an example of what you could achieve with full access behind paywalls to all papers and a lot of processing power applied to Text mining, NLP and deep learning?

Microsoft Academic Graph - Glimpse of the future?

Microsoft Academic Graph isn't quite as good as a 100% OA world, because we still have to rely on them to extract things , but things are worse than that. As you probably know, they will be discontinued at year end 2021.

Goodbye, Microsoft Academic – Hello, open research infrastructure?

Currently, there are many discussions around the coming loss of Microsoft Academic Graph. Work has focused on analyzing what is currently in Microsoft Academic Graph that is unique and none-overlapping from other open sources like Crossref.

See for example Bianca Kramer & Cameron Neylon's amazing overlap analysis behind MAG and Crossref. [Recording]

While we are not too bad off in terms of certain metadata fields as there is substantial overlap (e.g. references) and there are some metadata fields we will be in trouble (e.g. Abstracts & Affliations), the main thing that struck me is that no matter what happens we will definitely not be able to duplicate Microsoft Academic's unique "Field of Study".

Note : Even with Microsoft Academic "going away" at the end of 2020, the data is all licensed under a open license, so presumably you can still use the past data. This analysis is just a estimation of what will happen going forward I think.

I think of Field of Study has Microsoft's attempt to create the first ever cross disciplinary controlled vocabulary. Think MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) but automatically generated and for all disciplines.

This is a wonderful complex and dynamic system of over 700k concepts extracted and arranged into a six-level concept hierarchy. (See Technical Paper) and in a sense this is a large part of what makes Microsoft Academic - Semantic.

While we could with some effort, get publishers to deposit abstracts into Crossref and make them open (Hello I4OA!) and with some help of ROR.org get affiliations in shape but there would be no way to duplicate Field of Study.

After all which other organization has the clout to gain access to all the full-text in the world?

CORD-19 - another glimpse into the future

Another example of a glimpse in the future would be the CORD-19 (COVID Open Research Dataset).

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy(OSTP) charged the Allen Institute for AI to collect, assemble and make open a corpus of research text useful for research into COVID-19.

Assisted by powerful organizations like the National Library of Medicine (NLM),the Chan Zuckerburg Initiative (CZI - behind the soon to be discontinued Meta), Microsoft Research (behind soon to be discontinued Microsoft academic), Kaggle etc, this group went to the publishers and preprint servers to obtain full-text for use during the pandemic.

As I covered in my blog post last year, the group didn't simply go collected everything and released it. They had to do a lot of work to ensure the corpus could be fruitfully used. Some tasks included

Deduplication

Harmonization of existing provided metadata from various sources (also choosing a canonical/main version) and

Processing the full-text to parse the files to produce more structured data and formats (PDF to Json) more suitable for use

Microsoft Research did mapping of MAGIds to the CORD-19 dataset, others did other mapping e.g to CAS Registry of chemical substances and produced embeddings.

Again all this shows that for a Corpus to be readily used, you don't just get the full-text and release it willy nilly, you need to do a lot of prework.

I won't go into the various uses of CORD-19 dataset done by the community , e.g. Discovery tools, semiautomation of living systematic analyse etc as they are all covered in this post from last year.

CORD-19 is even closer to the future of a OA world than Microsoft Academic, because while researchers could rely on the metadata and parsed data done by the Allen Institute for AI, they also had access to the full-text and could do whatever text mining they wanted.

The catch is this is reliant on the generosity of the publishers who contributed non-OA full text to CORD-19. As it is, at time of writing some publishers may already be withdrawing permission to use the full-text.

A new development - Carl Malamud's "General index".

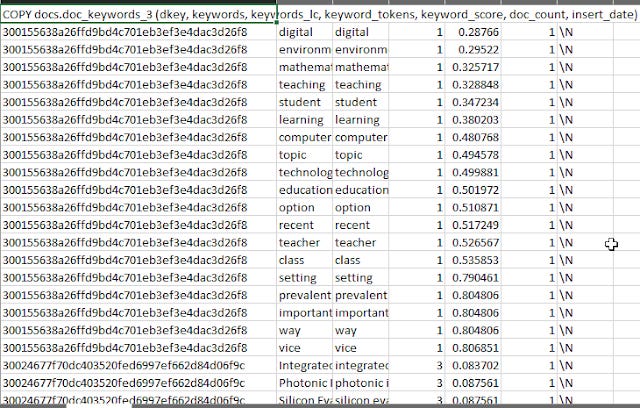

As I write this, I have just learnt of the release of Carl Malamud's "general index". which has data extracted from 107 million journal articles. This includes

a table of unigrams to 5-grams extracted from using SpaCy. This works out to 355 billion rows of a ngram with journal article ID (md5 hash)

a table of keywords generated using Yet Another Keyword Extractor (Yake). This works out to 19.7 billion rows, each with a keywords and an article id.

and of course a table that associates the article ID with the usual article metadata e.g. doi, title, pubdate etc.

ngram sample table

Keyword (extracted with Yake) sample file

What are some possible uses of this "general index"? Can it be used to supplement upcoming replacements of Microsoft Academic such as OpenAlex?

There is already an example of how the General Index was used and I personally found the series of short videos on the project here helpful.

The main thing, I picked up from the video is that General Index is still evolving and other extracted features might still be added. In particular, it was mentioned IDF - inverse document frequency for the ngrams might be added.

Another issue as discussed in the Nature article covering this is the legality of doing this and making it open. While it is true that text mining extracts can be considered facts and facts cannot be copyrighted, there is a question on whether

Malamud’s obtaining and copying of the underlying papers was done without breaching publishers’ terms.

Interesting enough Singapore recently amended it's copyright laws to have a Text mining exemption, that I think allows text mining ("computational analysis") for commercial and non-commerical uses as long as the user has "lawful access" to the content. This is I think somewhat similar to what is in the UK (except for non-commerical only) and other countries.

3. Open infrastructure is important.

I have said it before, the announcement that Microsoft Academic was closing shocked me into realizing open data isn't enough and that we need to pay attention to create sustainable open infrastructure.

Also consider that while the easy availability of open metadata and full text has encouraged an explosion of ideas and innovation in certain areas (see citation tools above), because even small startups or individual researchers can now try out ideas to create open indexes or literature mapping tools, it is almost certain that many of them if they get successful will be acquired by commerical interests.....

It just so happens this week, there was a release of the following post on LSE Impact blog - Now is the time to work together toward open infrastructures for scholarly metadata that explains the issues far more eloquently than I can (though my name is attached).

What I can add to this blog post is since this post was launched, Facebook accounced their corporate rebranding to Meta.

However at the same time there was this other small piece of news that was probably ignored by the world at large (except for Scholarly Communication geeks)...

https://t.co/7ONppnr043 will shut down in March. Post doesn't mention the Facebook➞Meta rebrand, but surely related. https://t.co/fogjqAnrR9

Another great example of why we need POSI for open infrastructure. https://t.co/ILNcILrmQc— Jason Priem (@jasonpriem) October 28, 2021

Now imagine if it was Google Scholar, which is pretty much a very important part of the research infrastructure used by thousands if not millions.....

Conclusion

One trend I have noticed about Open Access week is we seem to be moving to broader and more abstract goals. It used to be most of our energies were spent on a fairly concrete goal, making papers open, but now perhaps there is growing recognition by some that we should also consider the conditions (Open Science, Open Infrastructure) needed for which Open Access can truly flourish to benefit society.