Some readings I read in 2021 that made me feel like I levelled up

As a generalist and dilettante in the field of academic librarianship, I highly appreciate works that

a) Provide a concise summary of the key ideas and insights of the field and/or

b) Update or clarify a point of contention that was confusing (to me) before

Such works are rare but reading them usually makes me feel smarter for reading them and at times I could almost feel the mental fog in my brain on a certain concept or idea receding a little bit.

It occurs to me that my blog posts are often an attempt to produce similar works by synthesizing what I read to produce a coherent narrative or explainer of a concept or area, but I don't often succeed.

Looking back in 2021, which were some of these readings for me?

Exploiting the fact that such readings tended to make me want to tweet my new understanding, I looked through a year's worth of such tweets tagged with [Read] or [Watched] and I selected some of my favourite readings I discovered and read from 2021 below.

For those who want to go direct to the readings, this is the list.

1. Learning more about Causal Inference - Youtube playlist by Economist Nick Huntington-Klein on Causality

2. Clarifying CRIS/RIM/RIS concepts - OCLC report - Research Information Management in the United States (parts 1 &2)

3. Electronic resource management in an Open Access World - TERMS 2.0 and article - Electronic resource management in a post-Plan S world

4. Research Data metrics , standards and frameworks - Open Data Metrics: Lighting the Fire

5. A review of open citations and where to go from here? - Academia’s missing references & FORCE11 Community Discussion on Open Metadata

6. Misc - everything from readings on citaton techniques for recommendations of literature to text mining uses for systematic reviews.

1. Learning more about Causal Inference

When you are in academic librarianship, you run into a lot of situations where you want to show causality. Did a certain change you did e.g. change in IL technique, change in website or policy, really cause an increase in usage or improvement in student performance? (See also the Academic Library Value Research Agenda in the 2010s)

I have never been satisifed with doing a correlation and then saying "correlation is not always causation" while acting like it is and over the years have been trying to understand this thing called "Causal inference" and looking into techniques like Randomised Control Trials, Propensity score matching, Difference in Difference, Instrumental variables, Regression discontinuity and more.

I even wrote a blog post in Jan 2020 trying to explain the concepts to myself using library examples, though in my hearts of hearts, I still felt I didn't fully get it.

More recently, I stumbled upon some recent work by a researcher in my institution. I was looking at the interesting, How and Why Do Judges Cite Academics? Evidence from the Singapore High Court and then came across Causal Inference with Legal Texts

The later was fascinating as it was basically an attempt to teach legal reseachers causal inference! Leaving aside my brain was blown by the discussion of legal " text-as-outcome, treatment, and de-confounding methods", it was an amazing primer on introducing the basics of causal inference. I don't pretend I could follow all the footnotes but as a general overview to get a sense of the concepts? Wow.

This inspired me to look around again and I stumbled upon a Youtube playlist by Nick Huntington-Klein an Economist from Seattle University that explained the concepts of casual inference.

To some extent, the series of Youtube videos went through techniques I had seen or read about before from Randomised Control Trials, Propensity score matching, Difference in Difference, Instrumental variables, Regression discontinuity and more.

But what it did was to wrap them all togetther in a coherent manner and one particular concept "closing the back door" was new to me as very helpful that made it all "click" (Also Collider Variables was mind bending) .

Perhaps it helped that at the time I was just finishing up a simple research paper which employed RCTs and while discussing the results with my collegue, I could finally see why RCTs was so powerful and what we could say for sure about the results and more importantly what we couldn't.

In the youtube videos, the focus was more on understanding then actual technique, with liberal use of examples using R to make things more concrete. At certain points, like during the video on Regression discontinuity, the professor suggested that students not in his class to "look away" because the technique he used wasn't quite standard I believe.

But for my purposes this doesn't matter that much, since what I was after was the intitutive understanding not the specific details of each statistical techniques (I believe there might be mutiple ways for some of them).

2. Clarifying CRIS/RIM/RIS concepts

There was an explosion of institutional repositories in the 2010s, after which discussion moved to this new class of systems sometimes called CRIS (Current Research Information Systems) / RIM (Research Information Management) and RIS (Research Information Systems).

I never had a clear understanding of this area as this class of software because unlike say Central index Discovery systems, they seem to be very broadly defined in functionality and the scope and responsibilty for them spanned the whole institution - covering not just the library but also the research office and more leading to great complexity.

Like many academic librarians, my understanding of what is going on in other parts of the institution can be limited....

Comparing across institutions seemed to be tricky, while there were software names people threw around like Elsever's Pure, Exlibris's Esploro, Digital Science's Symplectic Elements , Vivo and the now seldom mentioned Converis by Clarivate I found it really hard to grasp what was going on.

This is where the OCLC report - Research Information Management in the United States published in Nov 2021 comes in handy.

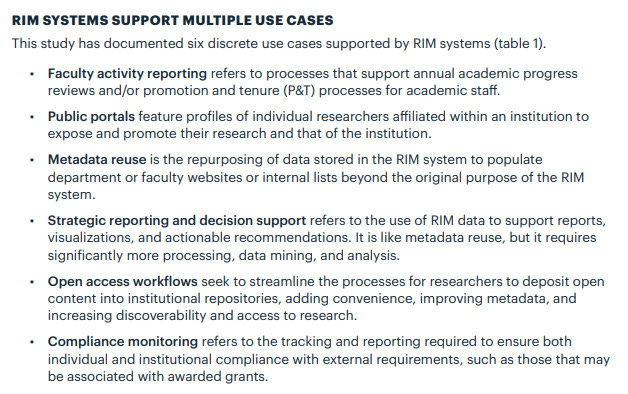

In particular, there is in my view an exceptionally clear delineation of the 6 possible use cases this class of software supports.

Not all institutions have software that handle these 6 cases, and from the more narrow point of view the academic librarian might be involved only in some of these areas that the institution might be working on (e.g. Some libraries are not involved at all in Faculty Activity Reporting).

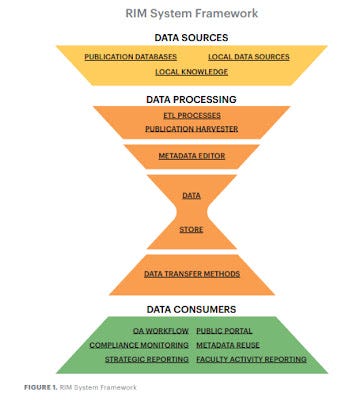

Another useful contribution is the "RIM System Framework" that helps visualize the system components by breaking them up into

Data Sources

Data processing (including storage)

Data Consumer

This RIM System Framework together with the table on stakeholders analysis is then used in part two of the report that provides case studies on the following institutions

Penn State University

Texas A&M University

Virginia Tech

UCLA (including the University of California system-wide practices)

University of Miami

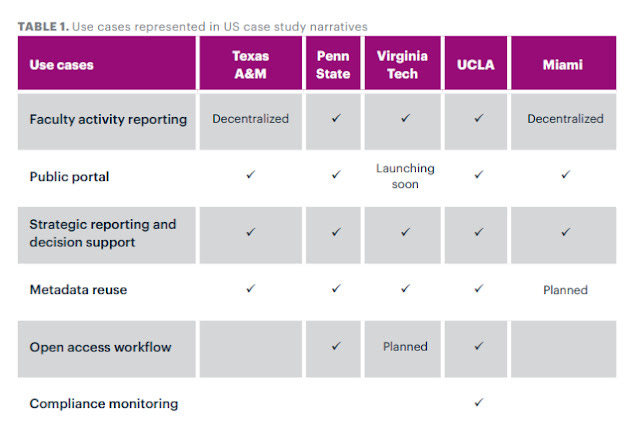

Part two of the report was more difficult reading for me as you started to see how different each institution was. In particular, no two institutions covered the same 6 use cases and for historical reasons many of them had multiple systems covering the broad functionalities of RIMS.

This is where the earlier frameworks paid off, since you now have a structure to compare against.

All in all I highly recommend this OCLC report, if you are like me and want to get a better sense of this class of products.

3. Electronic resource management in an Open Access World

I have been musing about how academic libraries would change when Open Access become the norm for many years now and even back then I could clearly see electronic resource management would change a lot particularly when Open Access levels started to reach a level where they might impact subscription decisions.

Of course, a lot of this was written prior to talk about Big deals in Open Access, Read and publish or Publish and read deals and things have moved quickly in the last few years.

This is where the article Electronic resource management in a post-Plan S world comes in. This itself is a supplement to TERMS (Techniques in E-Resource Management) which

"aims to set out the e-resource life cycle and to define a set of best practice using real world examples gathered from libraries in the UK and US. "

While not an electronic resource librarian, I suspect TERMS would not be a bad place to start learning about electronic resource management and it was updated to TERMS 2.0 in 2019 to take into account the rise of open access. Still time marches on, and the section on Open Access in TERMS 2.0 is pretty brief.

As someone who is now increasingly asked to consider big deals involving APC bundles, these resources are definitely useful as the world changes....

4. Research Data metrics , standards and frameworks

In recent years, I have been slowly thinking about the issues around research data discovery.

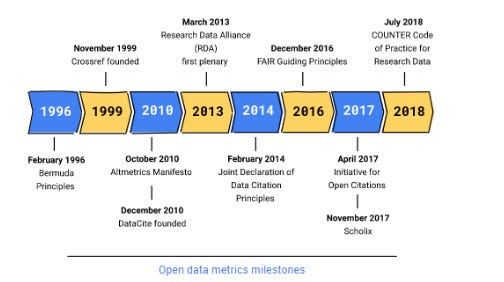

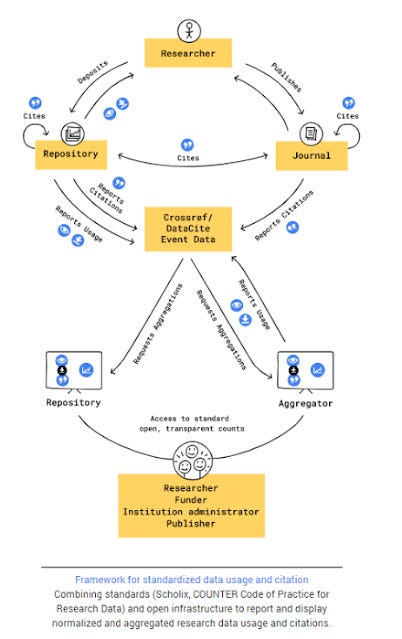

I've blogged about and wrestled with understanding Scholix , (Crossref and Datacite citation links), Google Dataset search (importance of schema.org), Data Citation Roadmap for Scholarly Data Repositories (and publishers) , Make Data Count and The COUNTER Code of Practice for Research Data, FAIR principles , Datacite commons, concept of PIDs and more.

Throw in people mentioning organizations like FORCE11, Research Data Alliance (RDA), Initative for Open Citations (I4OC) and Initiative for Open Abstracts (I4OA) and it can be hard to see how they all fit together.

It would really be nice for something to read that tried to explain all these different concepts, frameworks/standards and organizations in one coherent narrative.

The closest I have come across is Open Data Metrics: Lighting the Fire which was written in a five-day Book Sprint and coauthored by big names from DataCite, CDL, Crossref etc.

Even though it was written at the end of 2019, I only discovered it recently, but I think it still covers most of the developments you need to know, barring a bit of an update for Datacite commons/PID graphs & maybe the Meaningful Data Counts research project as well as launch of Google Dataset Search.

At 96 pages, it doesn't go deeply into the technical details (not needed for most librarians including me), but gives you a good basic understanding of the issues around managing datasets, a discussion of data citation and usage metrics and a overview of important emerging manifestos, principles, standards and organizations around research data.

I particularly like the discussion and figure titled "bringing it all together" on page 56 and 57, that shows how combining standards (Scholix, COUNTER Code of Practice for Research Data) and open infrastructure can report and display normalized and aggregated research data usage and citation!

As I have already done quite a bit of piece-meal reading of these topics for the last 3 years at least, so most of the concepts mentioned were not new to me but I appreciated being able to see how they worked together.

Someone new who had never encountered Scholix or COUNTER Code of practice for Research Data, or had limited understanding of Crossref/Datacite would probably find it a bit less clear, but I guess if you are a academic librarian who has no background but wants to get a fair shot of understanding the big issues around research data on a high level, starting here shouldn't hurt.

5. A review of open citations and where to go from here?

Somewhat easier than data citations to grasp I think for most academic librarians is the issues around open citations and over the years I began to read more and more deeply into these issues. I even enjoy going into the details sometimes.

As a sidenote, I started to realize a lot of articles I enjoyed reading in bibliometrics etc were most often published from one journal - Quantitative Science Studies. This journal was formed after the editorial board revolt from Elsevier's Journal of Informetrics in 2019. Ironically one of the three demands which to make all article reference lists of the journal articles freely available (as per I4OC) is no longer a sticking point as Elsevier has agreed to do this after signing the DORA statement. In any case, QSS seems to be doing very well.

This year for example, I enjoyed reading to some depth a discussion on Internet Archive's new open citation graph - Fatcat

If you having been paying attention, the Initiative for Open Citations (I4OC) has succeeded beyond most people's wildest dreams and pretty much the vast majority of records with references in Crossref are now made open.

Yes this includes record from major publishers like Elsevier and ACS and as a result - Coverage of open citation data approaches parity with Web of Science and Scopus

Where do we go from here? I found OpenCitation's David Shotton piece - Academia’s missing references a amazing summary of what else we might still do to expand the open citation graph.

Some suggestions include

Getting the last remaining publishers who continue to keep their references in Crossref closed to flip to open (e.g. IEEE)

Encouraging more publishers to deposit references into Crossref

Scraping references on publisher webpages for publishers that do not deposit references into Crossref

Connecting citations between Crossref DOIs to other DOIs (e.g. Datacite) and even other PIDs

Mining references within PDFs of scholarly works lacking DOIs

It's kind of crazy to think we are at the point where the first point is mostly done, and new projects like Fatcat, OpenAlex are trying to hit the other points.

Of course, given that open citations can be seen by some to be in a fairly decent state, attention is now shifting to other scholarly metadata and a recent FORCE11 Community Discussion on Open Metadata is definitely worth looking at.

In particular, I like how they conceptualize the road to open metadata as a blend of three approaches

Advocacy / persuasian (to publishers to make such metadata freely open)

Harvesting (e.g. Google Scholar/Microsoft Academic approach)

Community curation (basically crowd sourcing)

The last point I think is an approach that is less commonly done currently but I think might become a more prominent route in the future with organizations like Crossref experimenting. Still such approaches require that tracking provenance becomes a important issue.

This is also the year where developments like the closure of Microsoft Academic Graph, Meta has opened my eyes to the importance of going beyond open data and to pay attention to open infrastructure.

Here I will be bold and recommend two pieces I coauthored with others that were published on the LSE Blog if you want to be caught up

Goodbye, Microsoft Academic – Hello, open research infrastructure?

Now is the time to work together toward open infrastructures for scholarly metadata

6. Misc

In 2021, I also did a lot of reading around the effectiveness on the use of citation tracing and pearl growing techniques for exploring literature review, given my continued interest in tools like Connected Papers, ResearchRabbit, Litmap, Inciteful and more.

Some twitter threads that resulted can be found here and here. I also enjoyed this paper entitled Using Citation Bias to Guide Better Sampling of Scientific Literature

Another paper that caught my attention was - Creative Destruction: The Structural Consequences of Scientific Curation which tried to answer the question are you better off if you are cited by a review paper or not? On one hand, being cited by a review paper, could make your paper more noticable, but on the other hand, people may decide to cite the review paper instead of your paper...

This year I also looked more into learning about systematic reviews and ran into review papers on the uses of text mining for systematic reviews which taught me a lot.

I also continued my interest in Deep learning and language models since the rise of GPT-3, and found this new piece that tries to explain from scratch how transformers which are key to deep learning work. Requires zero background (it explains matrix multiplication etc). Another amazing site explaining all these concepts is https://jalammar.github.io/ .

e.g. How GPT3 works https://jalammar.github.io/how-gpt3-works-visualizations-animations/ . I confess I understand usually only 50%-70% of this but it is still interesting.

Also CSET Truth, Lies, and Automation: How Language Models Could Change Disinformation report was a meaty mind blowing report on how easy it was to try to use GPT-3 to generate disinformation. Highly recommended! (See tweet highlights).

I also read the somewhat older but still very enlightening - An Exhaustive Guide to Detecting and Fighting Neural Fake News using NLP which looks at it from the other direction to see how effective techniques are to detect "Neural Fake news" ie, fake news generated from neutral networks including language models.

Conclusion

All in all 2021 was a fairly fruitful year in terms of learning and expanding my knowledge base. Something that is critical for academic librarians who want to remain relevant.