Thinking of the future - a summary of my thoughts as of 2018

I was recently invited to the OCLC Asia Pacific Regional Conference Meeting 2018 in Bangkok to speak. The conference had the theme "Game Changer" and I gave my thoughts on how I see the game changing for libraries in the years to come.

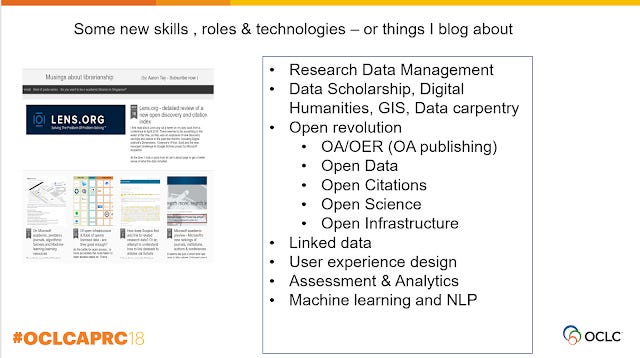

For the past 2-3 years, I have been blogging on various trends and technologies like analytics, open citations, open data, linked data, data carpentry, PIDs and even Machine learning, as such I took the opportunity to zoom out a bit and try to organize my thoughts on what exactly I was studying and why they were important.

What follows is not exactly my talk, but something based on it.

Trends affecting academic libraries

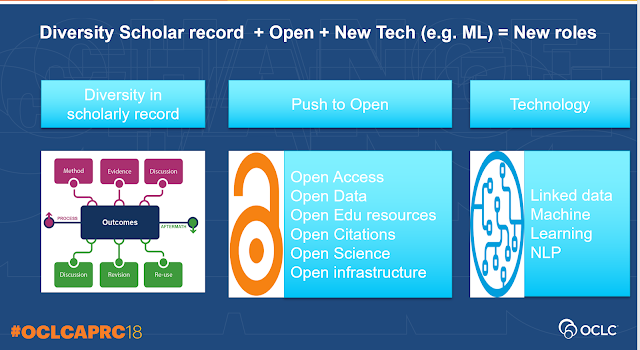

This slide above is in the nutshell is the way I think about the biggest drivers of change in academic libraries for the next decade or so.

Firstly, the primary duty of academic libraries - the collection of final published material and outputs for their community to use is diminishing in importance and focus has moved toward collecting artifacts across the whole workflow including collecting inputs, processes and outputs. OCLC calls this the evolving Scholarly Record.

Secondly, not only has the scholarly record become more diverse, but there is now an almost default presumption or at least an expection that these records be made open in some way. We are no longer talking about just making published papers open (open access), but also open data (raw files, code, protocols, peer review and more), open education resources, open citations and now even open infrastructure.

Lastly, it's perhaps a cliche to say we live in a time where AI in particularly machine learning , deep learning, are changing jobs. But given the first two trends where more and more about the scholarly communication system is collected and made open it is no surprise I'm seeing more and more new applications emerge based on blending these technologies with the data collected from the Scholarly Communication system.

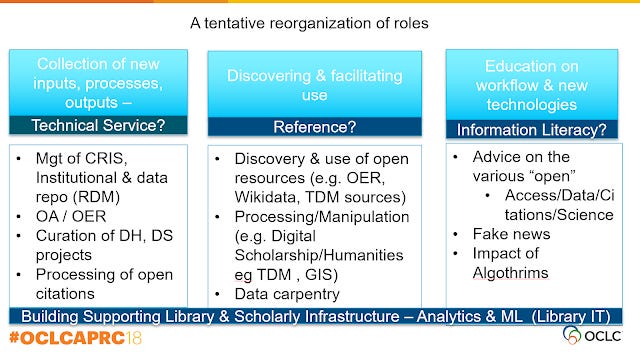

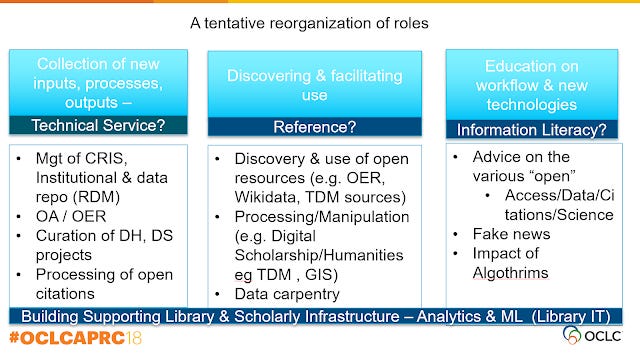

The next slide provides my very speculative view on how the activities of academic librarians will change as a result.

Notably I expect a lot of academic librarians jobs will shift from outside-in to more inside-out activities.

I elaborate on both slides further below.

What we are collecting and how we are collecting things are changing

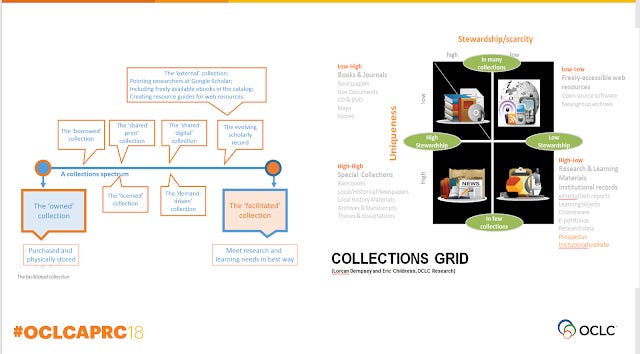

I'm sure most readers of this blog are familar with concepts like the collection spectrum and collection grid popularised by OCLC research.

Basically, there is a shifting focus away from just collecting items of low uniqueness (e.g books , journal articles) towards focusing on collection of items of high uniqeuness (eg special collections, thesis of University, data outputs etc). We might even be starting to collect items we haven't traditionally collected like open education resources.

Even for things we traditionally collect like books or journals, we are collecting in a different way, we are owning less and less of the collection but leasing or even faciliting access to shared collections.

Of course, the reason why we are moving towards collecting unique items and away from more common and traditional materials is the trend towards open access, which might possibly diminish the academic library role in providing access to journal articles as we no longer pay directly for access for our users though we may have other roles to play such as management of APC funds, negotiation of transition to OA world , managing of repositories etc.

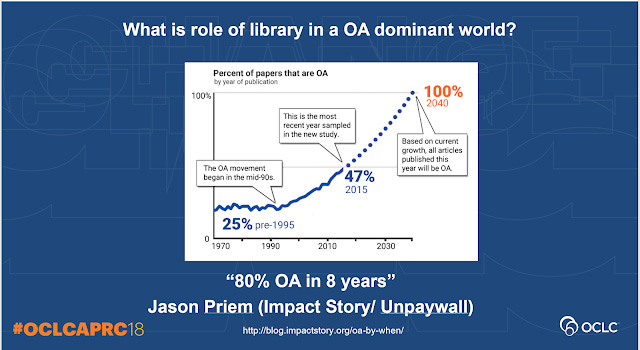

At this point, I would thought most people would expect the future to be open access. Projections by Impact Story people suggest 80% OA (I assume 80% of yearly output) would be achieved in 8 years.

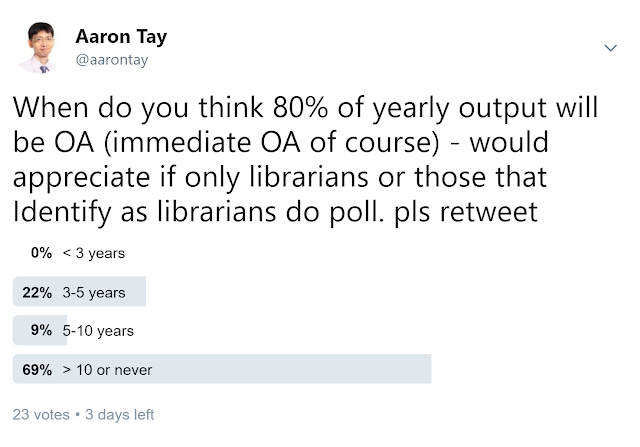

But is this projection too optimistic? Will the trend level off at say 60% say? It seems most librarians I polled are doubtful about this 80% in 8 years prediction.

I apologise for this informal Twitter poll, in particular I'm allowed only 4 options so I could not create a seperate 5th category for "never".

As you can see, merely 31% of those polled though OA levels of 80% will be reached in less than 10 years and this matches the hand poll, I did during the talk (actually the hand poll was even less optimistic)

Given that librarians on Twitter are likely to be more well informed on open access trends than average, this isn't due to lack of knowledge.

My sense is academic librarians have been told OA would be coming for a decade or more already and past failed promises and broken dreams with IRs etc have made most of us jaded. For example someone felt that the publishers are very clever and will keep finding ways to block the movement.

While I always marvel at how savvy and strategic minded Elsevier etc is, I think it is not always true that Publishers would oppose a OA world. Indeed a OA world could come - as long as it is on the terms of the publishers. Why wouldn't publishers be happy with a OA world where they recaptured as much if not much than what they get now via APCs?

Perhaps we are focusing too much on the 80% in 8 years figure. The greater question is at what level of OA would the academic library start to reconfigure their services drastically. Would it be a gentle transition or a sudden shift? I asked this question back in 2013 in How academic libraries may change when Open Access becomes the norm and I still have no idea how to answer this. More about this later.

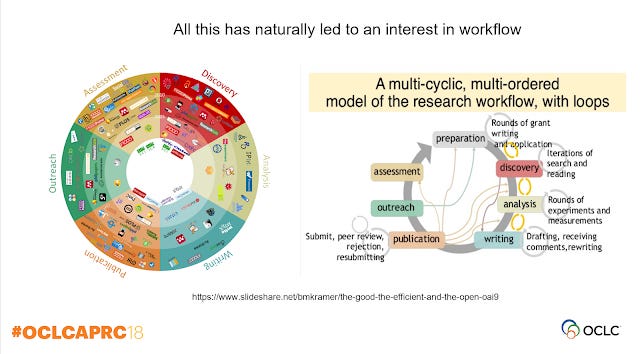

Increased focus on the Workflow

I think it's fair to say that in the past academic libraries focused on mostly collecting or more accurately providing access to published final outputs like journals and books and mostly ignored many phases of the researcher workflow beyond some what superficial support of discovery and perhaps the citing portions in the writing stage.

Over the years we have slowly started to gain expertise and experience in areas like citation metrics (assessment), managing of institutional repositories, ORCID (outreach) ,parts of analysis and publishing parts of the research workflow (RDM, Digital Scholarship/Humantities, data carpentry) etc.

Chi: Librarians today are so ready to be a part of the research workflow tools. "Ten years ago we had to go around the librarians. That was a stated goal." #ithakatnw18

— Roger C. Schonfeld (@rschon) November 29, 2018

This is in line with both the greater focus on more than the published output as well as some hedging to find new roles to replace the ones likely to be lost as open access gains a foothold.

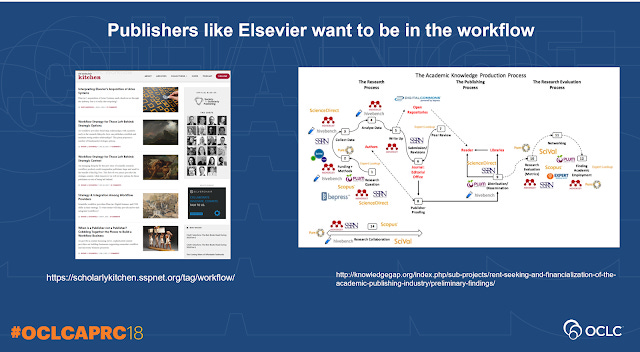

Of course publishers have the very same idea.....

If you read Scholarly Kitchen Blog , it's hard not to notice all the publisher talk on "workflow".

Part of it of course is a hedge against the traditional publishing business becoming less profitable. Coupled with the trends towards looking at the whole ecosystem of research rather than just the outputs, it is on hindsight and obvious thing to do for those looking for new markets.

Upstreaming: The Migration of Economic Value in Scholarly Publishing suggests there are three way to monetize this upstream move.

Firstly and most obviously is to build and sell the tool directly. Secondly, in place or on top of it to sell analytics around use of the service. Mendeley Institutional edition besides providing additional storage space, also provides analytics for the institution is an example.

Lastly, the third strategy is to offer tools bundled with content.

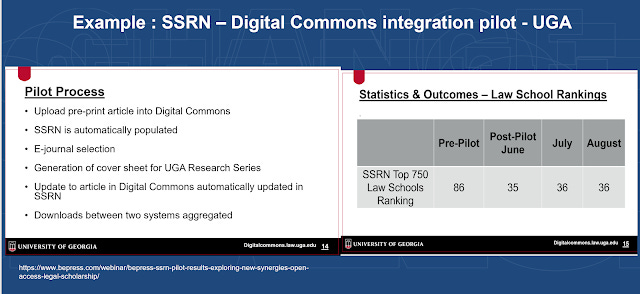

SSRN and Digital Commons - an example of lock-in workflow

With workflow plays companies like Elsevier are beginning to gain strong lockins in the workflow. Readers are of course aware of how Elsever pretty much has a foothold throughout any stage of the workflow.

Some plays are obvious like combining multiple logins to one login or allowing more seamless hand-offs but here's a recent play that shows how a clever company can go beyond it.

As everyone knows Elsevier has acquired both SSRN and Bepress (Digital Commons).

Many institutions like mine use SSRN heavily, and have working paper series in Law, Accounting, Finance etc as well as use Digital Commons for our Institutional repository.

A recent pilot enabled intergration between the two where you can upload preprints into Digital Commons and it gets populated in SSRN. The clever part of it is that not only does this makes thing seamless, the system also aggregates downloads from both downloads from the Digital Commons Institutional repository and SSRN!

If you don't get the significance of this. Consider this. One of the reasons reseachers often cite for not depositing their preprints to our Digital Commons systems is that they don't want to "dilute" downloads attributed to their SSRN papers. I understand in some disciplines, rankings on SSRN at indivdual or institutional levels are taken fairly seriously and try as we might to show that there is some evidence that IRs and SSRNs are drawing different audiences so this dilution effect doesnt exist, what this tieup is offering turns this issue into a strength.

As seen in the slide above the University doing such a tieup shows a significant rise in ranking from 86th to 35th in the Law school rankings after the pilot.

This is a scary example of lockin, knowing this how many libraries will go ahead with "operation beprexit"?

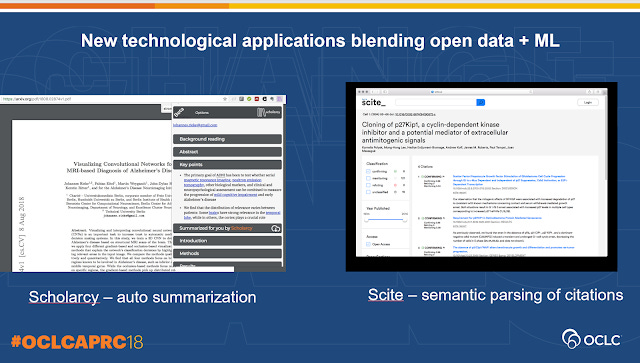

More open data + Machine Learning = New applications

My blog began ten years ago as a place to document new interesting tools in academia that exploded around the rise of social media and I maintain this interest to showcasing new tools. Recently I've been noticing the same thing is happening for tools that apply Machine learning, NLP and linked data.

Of course we are all aware of the rise in Machine Learning but machine learning is nothing without data to work with and the past decade has been accompanied by a rise in the amount of open data that we can work with.

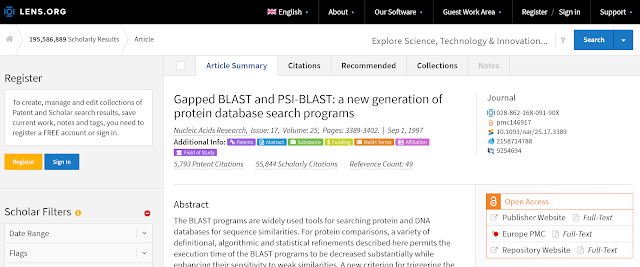

The rise of open data on and about the Scholarly Communication system

Looking back at 2018, I think this was the year that not only open data on and about the Scholarly communication system hit a tipping point, but products and tools started to appear based on them,

Whether be it open access papers (for Text data mining), open data, open citations there is so much more now. There is an open question right now if this development favours the more open tools as opposed to more closed commercial entities

There are many examples of tools that have started to appear that combine and make use of this data, but perhaps the best example of a tool that uses the open data deluge is Lens.org . (Dimensions is a commerical example) I've reviewed Lens recently but here's a short-recap of the open data sources and types it uses.

It blends together data from various open data sources - including

Unpaywall (information about availability of free sources)

CORE (for full text snippets matches)

Patents sources

A Lens record consisting of a composite of multiple open data sources

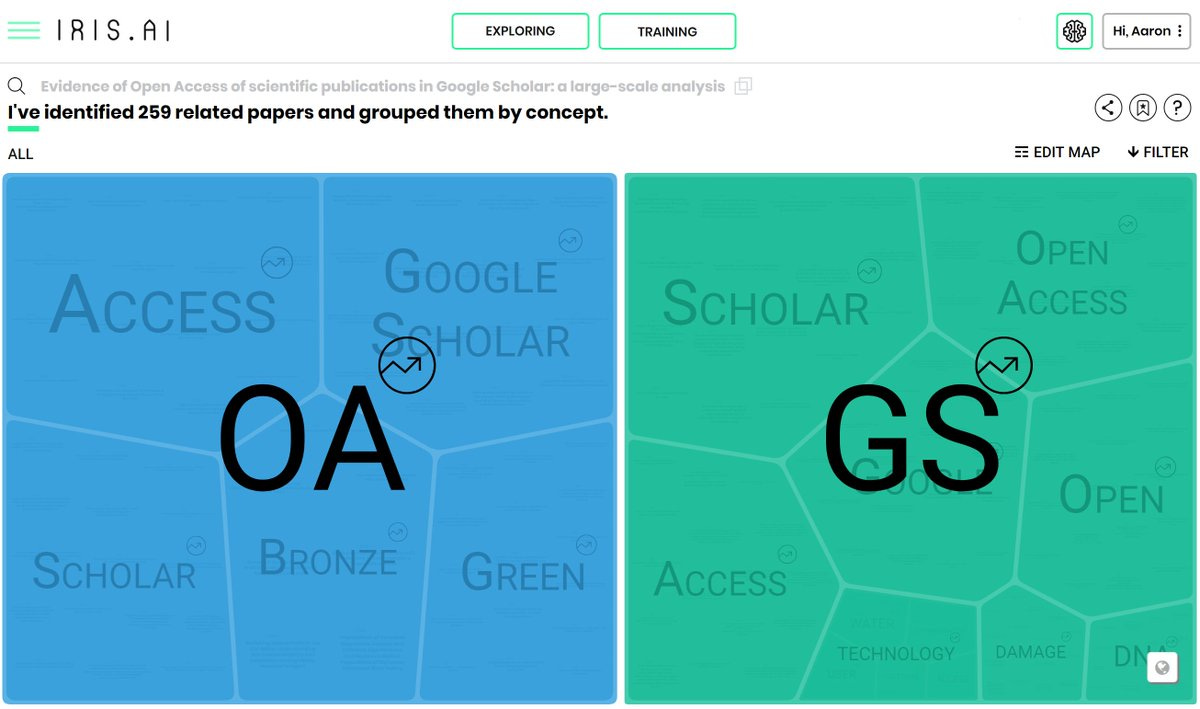

AI and Machine learning in Academic libraries

7 Ways AI Will Change University Libraries has a pretty good overview of how such technologies will be used in University Libraries, let me try to use that as a rough framework to illustrate some of the ways AI and Machine learning is starting to be applied with concrete examples.

The author of this piece is CEO of Iris.ai which uses AI and Blockchain..... I won't comment on the blockchain aspect since it is outside my area of knowledge.

AI in Indexing of Content and Document matching

This suggests that "New AI tools will allow automatic indexing of content that way surpasses human-made categories and fields, that allows for discovery and navigation across disciplines. " as well as "AI-assisted document matching."

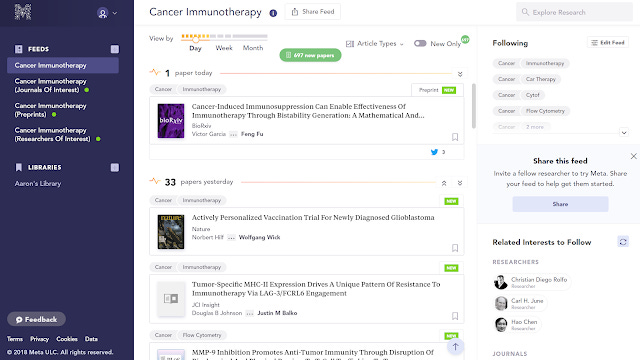

My assessment is that this is mostly already here, and I have a suspicion while efforts like Yewno, Semantic Scholar, Meta (in closed beta at time of writing) and Iris.ai itself will try to improve the state of art of document matching, this isn't an area where big improvements will be easy given past decades of effort in this area.

AI in Content Summarization

The idea here is that software will auto-summarise from full text of articles, book chapters and other items which will provide value to you by either

saving time by quickly highlighting or extracting key points or findings

help ingsimplify jargon so you can better understand the paper

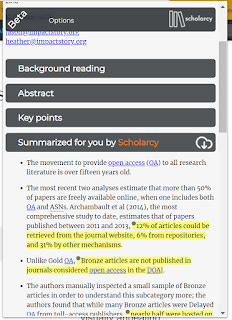

One of the players in this space is Scholarcy which I have blogged about . Another new player in the same space is Paper Digest.

Scholarcy Chrome extension summary

The main thing to note is these tools only work if they have access to the full text, which means you are restricted to doing this on Open Access mostly (Scholarcy has an API that can run on pdfs).

Of course we are in the beginning stages of seeing how this type of technology can be used in academia. My current preliminary thoughts are that summarization of journal articles will need to show significant value add (time saved) over just skimming the paper.

For instance something like the sadly departed Knowtro that allowed you to browse by findings would be amazing.

Another way to add value for such systems is to help readers who are unfamilar with the area better understand what they are reading or provide context.

Scholarcy background reading links to Wikipedia Articles

Scholarcy does some of this with linking to Wikipedia articles that Scholarcy detects as articles but this is somewhat basic.

More ambitious is the following undertaking by Impact Story - Get the Research

The idea is to use the 20 million open articles already harvested by Unpaywall and build "AI-powered Explanation Engine." to " finally cash the cheques written by the Open Access movement."

They will work on "concept maps, automated plain-language translations (think automatic Simple Wikipedia), structured abstracts, topic guides, and more." to add context to academic works.

This is where I suspect AI has the biggest potential to change the game and is rightly described by Impact Story has "blue ocean" strategy.

AI and the Citation System

This is another big area where the combination of open citations (both from the efforts of Initative for Open Citations to get publishers to release references and the large scale parsing of full text for references), coupled with Machine learning has great potential.

Past blog posts have talked about tools like Citation Gecko, VosViewer and how they use open citations to help find relavant articles. I have a blog post earlier this year that speculated on various ways discovery might improve and one of the ideas was rather obvious - could one do semantic parsing of citations such that you could not only find out that one article cited another but also the semantic meaning of the cite?

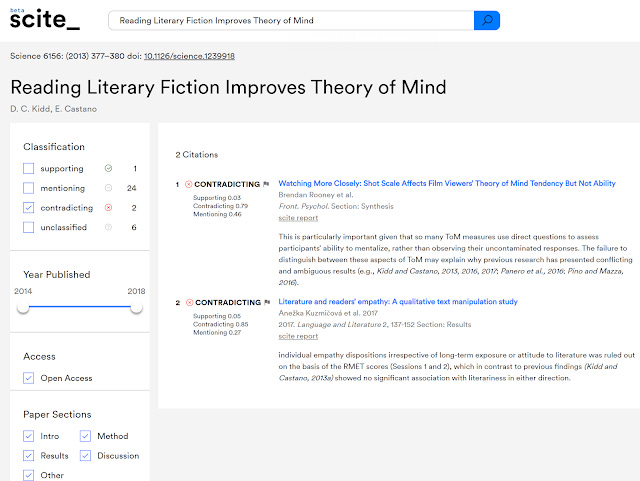

Scite (currently in closed beta) does this. It uses machine learning (supervised learning from manually annotated citations) to determine if a cite is "Supporting", "Mentioning" or "Contradicting".

I will probably be reviewing this in the future , but you should be able to immediately see the huge potential of this. In many ways, this is similar to the idea of CiTO, the Citation Typing Ontology which is meant to "enable characterization of the nature or type of citations, both factually and rhetorically, and to permit these descriptions to be published on the Web.", though perhaps this envisions researchers typing the citations manually.

AI in Quality of Service and Speech to Text to Speech

This refers to deployment of chat bots and smart assistants (Alexa) in academic libraries. I won't talk much about this because this isn't currently in my area of interest.

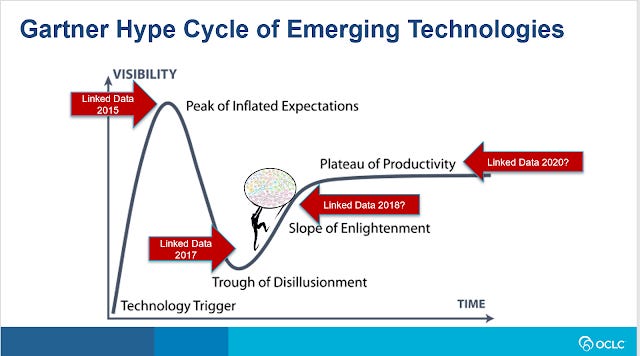

Linked data - moving up the slope of enlightenment

Linked data - moving up the slope of enlightenment?

Linked data, something we have been talking for it seems forever, may have perhaps turned a corner, in particular Wikidata/Wikicite seems to have big implications in the Scholarly world.

As I have just written a long blog post on Librarian efforts on Wikidata ,I will just say that given that libraries are now moving towards inside-out activitites there is a natural focus on enhancing discovery which linked data is meant to help facilitate. This is particularly true as academic libraries are now trying to collect and curate more than the traditional outputs of book + proving access to articles and the way to do it is unclear. Could linked data be the solution for enhancing discovery?

This is just the beginning. What fertile ideas can be unleashed on peer reviews (if made open), datasets, code, protocol, patents and more?

Some wild speculative thoughts about the future of academic libraries

With all this in mind, what is the role of the library and librarians in the future? Above I provide a tenative and very speculative view on academic librarian activities.

First off, as described above technical services will move away from a outside in approach towards more of a inside out approach.

I will just briefly describe some of these inside-out activities , for more see my last blog post on 6 inside-out activities librarians are doing.

Most libraries today manage Institutional repositories and to a certain extent data repositories. There are various roles in OA and OER that libraries are also taking up.

Digitzing and Curation of Digital content like Digital Humantities projects, maps are also becoming common place where academic libraries working on preserving such projects and making them discoverable.

As mentioned above, an inside-out role also places a greater focus on discovery of contents curated by librarians. Skills in linked data (Wikidata, Bibframe, Schema.org) , search engine optimization will be needed.

Even cataloguing standards might become more open.

"I take it as a given that the rate of scholarly production & resources that libs will be interested to catalogue has outpaced capacility of current cataloging practices to describe....only way ahead is thru linked open data and fair data " https://t.co/fdfQMVviXY #wikicite

— Aaron Tay (@aarontay) December 8, 2018

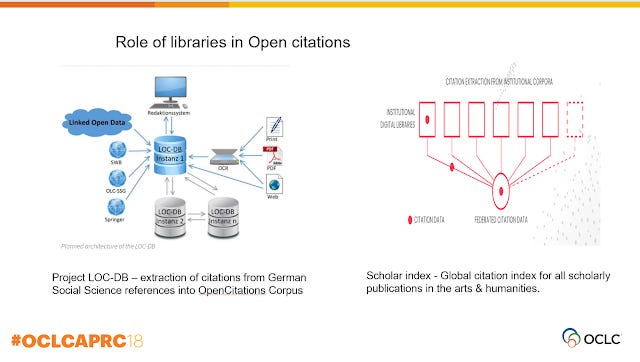

A somewhat newer and more speculative role academic libraries can play is in the role of provider of open citations.

I've blogged about Project LOC-DB before, a project by libraries in Germany to determine if it is possible to capture, process and release linked open citations data from Social Science Journal articles in German. Scholar Index is a similar idea but for arts and humanities .

Reference and User education

Another area which might undergo an even greater transformation would be in the area of reference.

In a open access dominant world, instead of spending time mostly teaching users how to access proprietary databases, the shift goes towards teaching users to discover and access open content and data.

In particular, academic librarians will have roles guiding users on sources for data work (text data mining, GIS etc).

Of course, there's also a lot of interest now in Digital Humantitites and Digital Scholarship , where the role of the librarian is not just to access information but also helping with methods to manipulate and process the data. Library carpentry which is useful in it's own right for library work, also overlaps highly with Digital Scholarship.

So awesome to see #WikiCite focused on how to expand the @wikidata community by helping @LibCarpentry flesh out our skills training modules for librarians! https://t.co/C0BZ83jPgx

— Library Carpentry (@LibCarpentry) November 30, 2018

Lastly, the future Scholarly ecosystem is likely to be a lot more complex and academic librarians can play a role guiding users past the complexities of copyright, open access rights and the traps and pitfalls of complicated work flows.

Areas like Open Science and it's focus on helping reproducibility and replicability provide yet more areas where academic librarians can add value.

AI impact on information literacy

Finally with AI rearing it's head there are new potential roles for academic librarians in education.

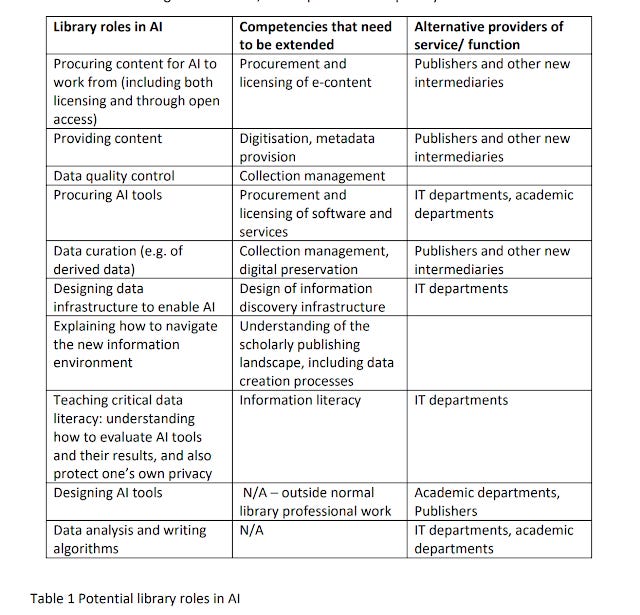

An interesting recent paper on AI and librarians list the following potential roles and skills needed

In particular, the impact of AI on information literacy is very salient on my mind and I'm looking on with interest the IMLS Grant RE-72-17-0103-17 granted to Montana State University Library - "will conduct an environmental scan of the field's knowledge of algorithms, develop a proof of concept search application employing common algorithms, and create an Open Educational Resource (OER) curriculum and pilot class that will be taught to librarians to improve digital literacy based on the algorithms that define online experiences and shape technology. "

Conclusion

Obviously nobody can see the future with clarity and this is my best guess of what is coming in the next decade or most probably two. A lot of this may not pan out, but it will definitely be an interesting ride.