Model Context Protocol (MCP) Servers - Wiley AI Gateway & PubMed - How Claude can now pilot test search strategies using PubMed

AI search tools like Elicit, Consensus, and Scite.ai have spent years racing to build centralised indexes of academic content— first by indexing the open content that is available and then trying to get publisher partnerships. But unlike their predecessors of the 2010s - the Web Scale Discovery systems (now called “Discovery layers” or “Discovery Services”) like Summon, Ebsco Discovery Service, Primo, publishers are much more wary of handing over content for indexing amid intense concerns about AI training on copyrighted material. The Model Context Protocol(MCP) offers an alternative path. MCP allows AI models to query publisher content directly through standardised servers, keeping full text on publisher infrastructure while enabling real-time retrieval.

Interestingly, this isn’t just an architectural workaround; it changes what’s possible. Using MCP, Claude can now pilot-test Boolean searches against PubMed, check MeSH headings, assess recall, and iteratively refine strategies—capabilities that were impossible when LLMs generated search strings blindly. For evidence synthesis and library discovery, this may be the most consequential development since federated search gave way to discovery layers.

Caveat: My understanding of MCP is still developing, so treat the technical details with appropriate caution.

Summary

The Model Context Protocol may fundamentally change how AI tools access academic content. Rather than building massive centralised indexes (the approach taken by Elicit, Consensus, and others), MCP allows AI models to connect directly to publisher content through standardised “servers.”

I’ve been testing two MCP servers: the Wiley AI Gateway and a PubMed MCP server .

My key findings:

MCP makes AI-to-content connections are more transparent: You can see exactly how your natural language query gets translated and what content (metadata, text chunks or even full text) is retrieved

Wiley’s approach is impressively open: They’ve shared their evaluation metrics with me and plan public transparency about search quality—a welcome departure from the opacity of traditional discovery vendors

LLMs can now pilot-test Boolean search strategies: This is huge for evidence synthesis. Rather than generating search strings blindly, Claude can actually run searches against PubMed, check MeSH headings, and iteratively refine strategies

History may not repeat: If you’ve been in libraries long enough, the architecture that MCP represents might sound familiar. We tried something like this before—federated search in the 2000s—and it failed. But the technology and incentives have changed in ways that matter.

Read on for detailed walkthroughs, JSON response examples, and my thoughts on what this means for libraries, publishers, and academic AI search vendors.

What is MCP?

MCP—Model Context Protocol—was created by Anthropic and released as an open-source standard in late 2024. I initially ignored it, but by 2025 both OpenAI and Google announced support, making it the de facto standard.

The USB-C Analogy

The easiest way to understand MCP is as a “USB-C port” for Artificial Intelligence.

Currently, most AI models are “walled gardens.” They have immense internal knowledge from pretraining but cannot easily access newer information or content they’ve never seen—such as your library’s subscription databases, catalogues, or repositories.

While most LLMs now have built-in web search tools to browse the web (kinda like a human), this method only accesses open content and tends to work slowly compared to direct API access to specific sources. However, this meants developers had to build custom integrations for every database they wanted the AI to access.

Defailt Web search in Claude, similar functionality exist in ChatGPT and Gemini

MCP solves this by creating a universal standard—an open protocol that lets any AI model plug into any data source instantly, without complex custom coding.

MCP servers can be used for taking actions beyond just search of course, MCP servers can write documents, send emails etc. Edit: Rod Page has shared with me how another use case is using Large Language Models and MCP servers to provide a user-friendly way to query knowledge graphs/linked data without requring the user to know SPARQL.

In short, the MCP servers you setup are like a menu that let the LLM/AI “know” what tools and functionality are available - which it can use when necessary.

The “N × M” Problem

Before MCP, the AI industry faced a logistical challenge. There are dozens of AI models (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Llama, etc.) and millions of data sources (PubMed, Wiley, JSTOR, Google Drive, Slack). Connecting PubMed to ChatGPT required custom code. Connecting PubMed to Claude? Different custom code. Every new AI model meant rebuilding integrations from scratch.

MCP acts like a universal power outlet. Instead of building a “PubMed-to-ChatGPT” connector, developers build a single “PubMed-to-MCP” server. Once built, any MCP-compliant AI can instantly plug in.

This explains why platforms like the Wiley AI Gateway exist. Wiley didn’t have to build separate integrations for every AI company—they built one MCP-compatible gateway. The same logic applies to libraries with open repositories. Previously, you’d have to decide: build a ChatGPT plugin? A Gemini “Gem”? Now you just offer an MCP server.

How MCP Relates to RAG

How does Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) relate to MCP?

RAG answers: “How do I find and use documents to ground the model’s answer?”

MCP answers: “How does the model call the search and document APIs that let it do that?”

Systems can use MCP as part of your RAG pipeline. We will discuss this distinction in future posts

MCP server - Tools, Resources, Prompts

MCP protocol consists of MCP host/client (e.g. Claude Desktop) and MCP Servers (e.g. Wiley AI Gateway).

I will ignore the distinction between MCP host and MCP Client for now

MCP servers can be on the cloud or it can be something run locally on your machine you connect to.

There are somewhat technial guides on how to do this to connect to academic sources. Most of these are to MCP Servers that connect to open content like Arxiv, Semantic Scholar, OpenAlex. Even though the default Web Search is likely to be able to access the same sources, a direct MCP connection is likely to be faster.

MCP servers consist of three main elements - Tools, Resources, Prompts

I won’t go in depth into the other two, but of these three elements, tools are probably the most important for us to understand because they are the “Verbs” or actions on what the MCP server allows the LLM to do.

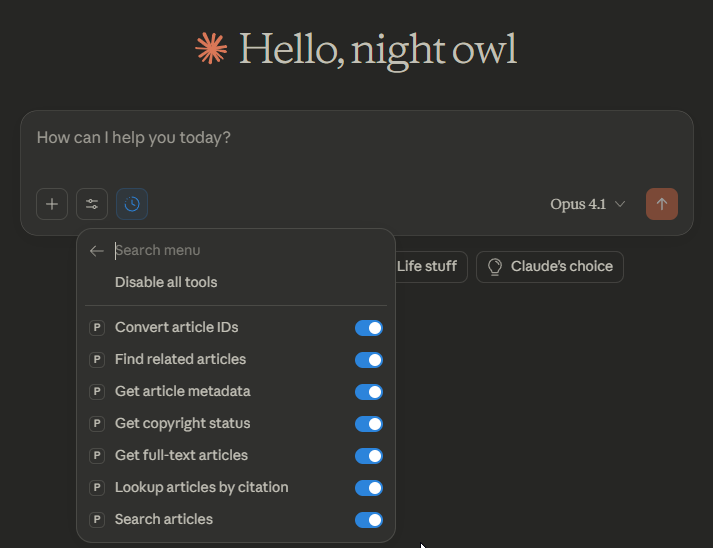

Here is an example of the “tools” available to the PubMed MCP server I connected to

This gives you an idea of what the PubMed MCP server allows the LLM to do and not do, which will be very important for understanding what you can ask for.

For example, from this list, you can probably guess asking the LLM to use this MCP server to find citations of a given paper probably won’t work (“Lookup articles by citations” refers to verifying citations and finding PubMed IDs from journal references).

It can “search articles”, “Get article metadata” and also retrieve 8 million full-text via PMC.

Learn more about the tools offered by PubMed connector.

My testing setup

For my blog series, I will be taking the easiest approach with no setup.

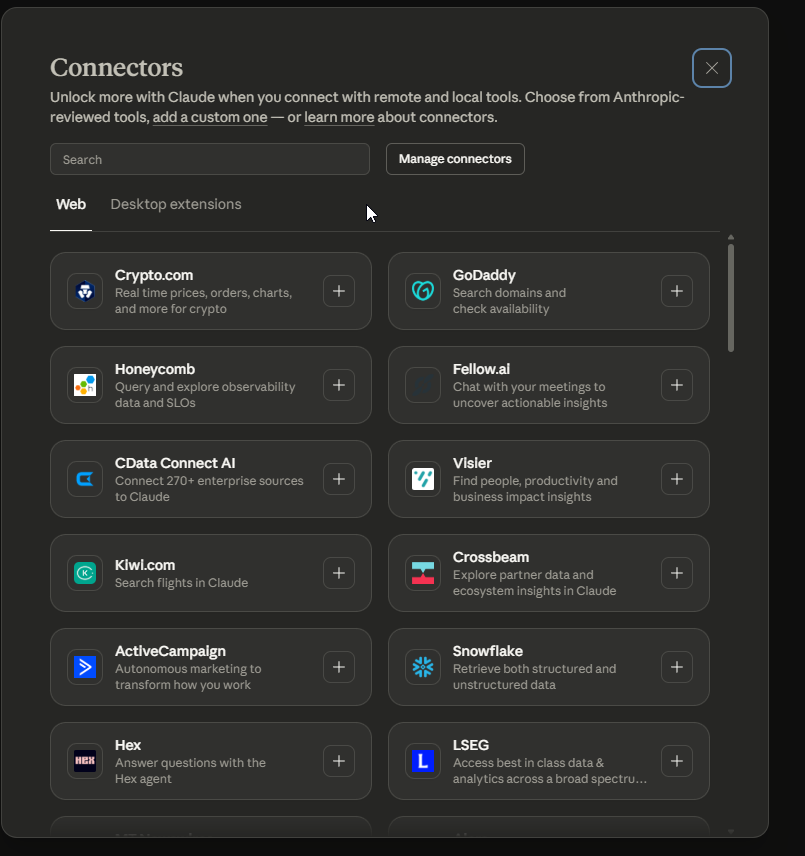

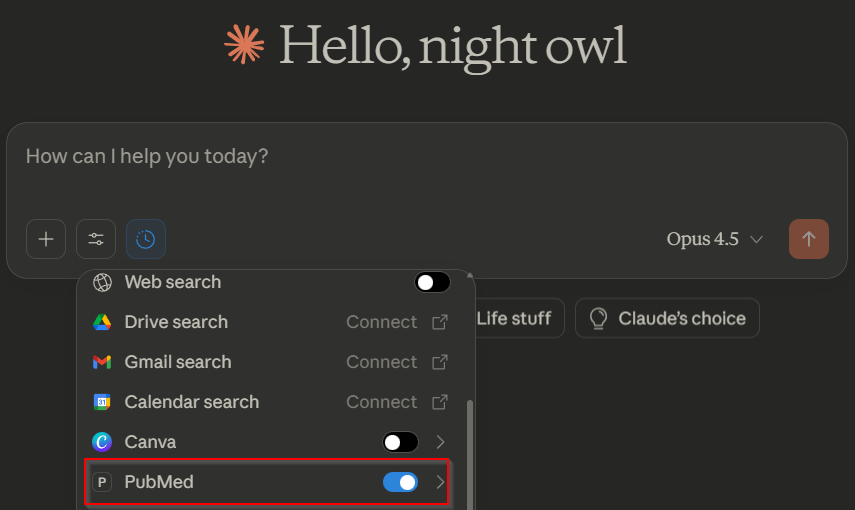

I will be using the Claude web interface (paid version needed) as the host/client and turn on connection to two specific connectors/MCP servers (connectors & MCP servers will be used interchangably) which are already available to be turned on without any additional setup.

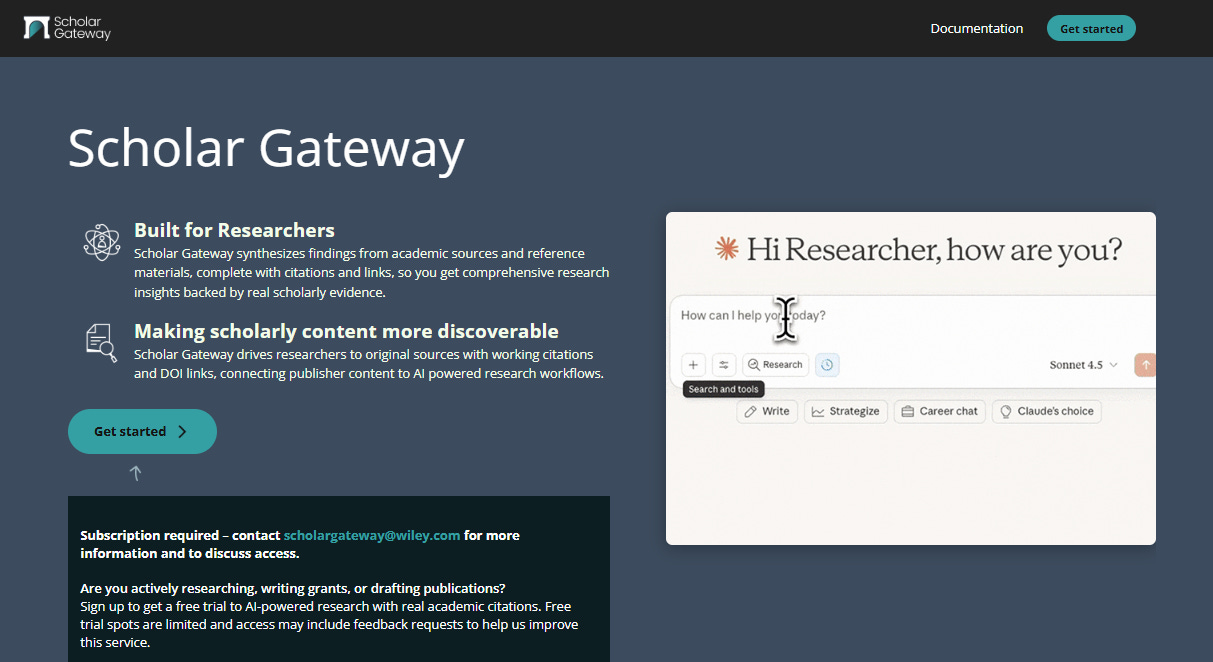

Wiley AI Gateway (listed as “Scholar Gateway” in the interface)

You can of course add a lot more connectors/MCP servers both default or custom ones.

I think with some setup you can possibly also connect Claude to other academic sources like OpenAlex, Semantic Scholar, Arxiv or use ChatGPT plus to connect to custom MCP servers.

Testing the Wiley AI Gateway

Wiley appears to be one of the first major scholarly publishers to offer an official MCP server, launching in October 2025. (Another early adopter is Statista.) Based on their press release, they support platforms like Anthropic’s Claude, AWS Marketplace, Mistral AI’s Le Chat, and Perplexity.

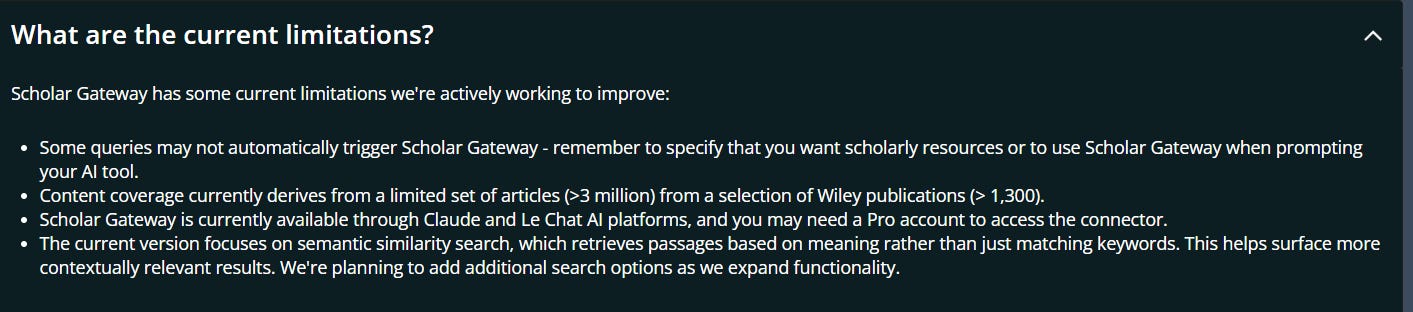

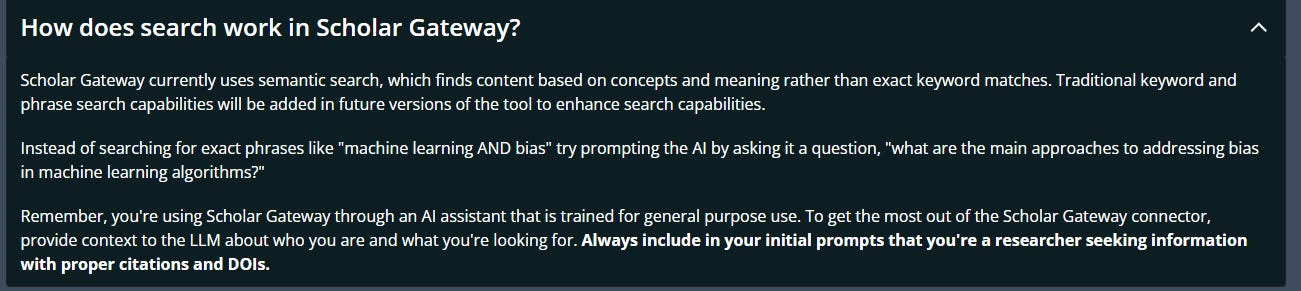

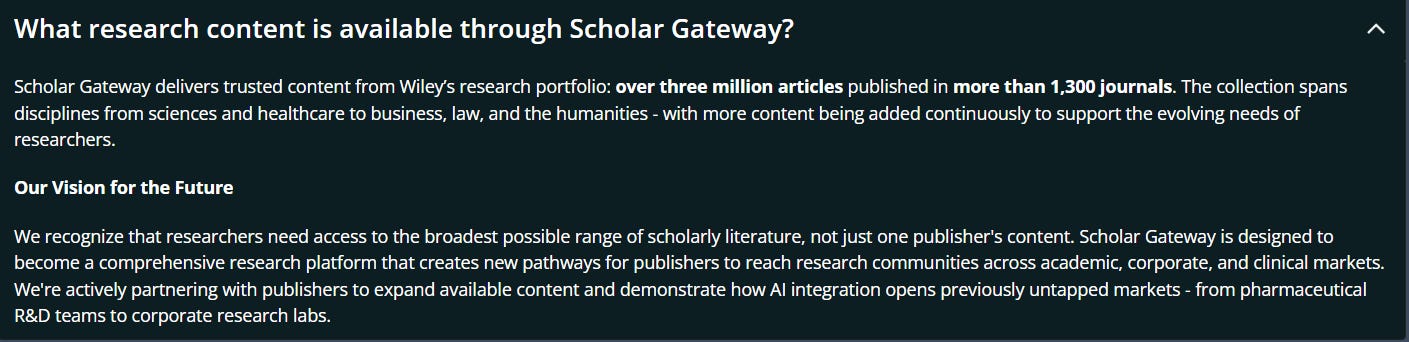

When you first add the Wiley AI Gateway to Claude, you will see this support page.

It provides a ton of information

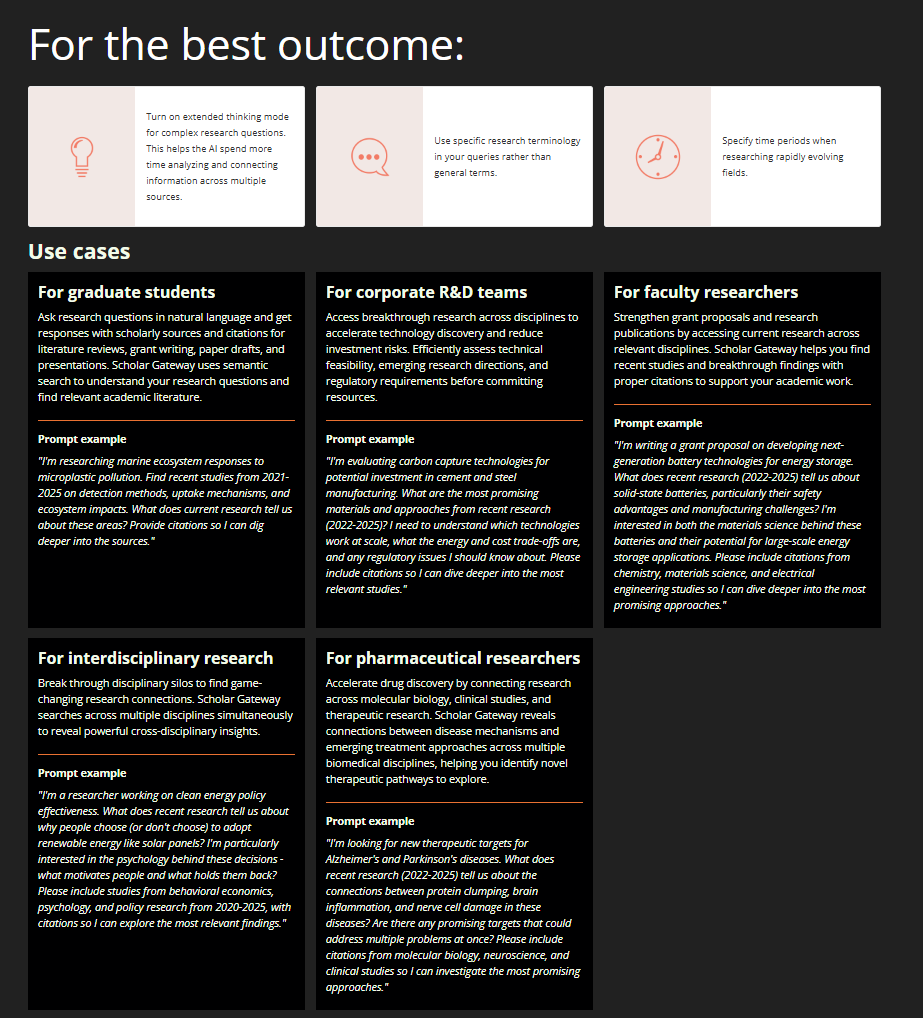

Even advice on how to prompt

and a list of FAQs, but there seems to be no easy way to go back to this page except by disconnecting and connecting again.

I was given beta access and I (or more accurately Claude) can theoretically access the entire collection of 3 million Wiley articles through the Wiley AI Gateway MCP server. In my tests below, I used either Sonnet 4.5 or Opus 4.5, generally without “research” mode enabled. I turned off web search and only enabled the Wiley AI Gateway connector.

As you will see later, both the Wiley AI Gateway and PubMed connector will fail for certain queries due to their limitations, but if you have the Web search functionlity turned on as well, it may be able to compensate for these issues

Transparency in Action

While the FAQ suggests I need to state that I am looking for schoarly resources or to use Scholar Gateway, I found it always used it correctly when needed, perhaps because I turned off the other connectors like default web search.

One thing I didn’t appreciate until testing was how transparent everything is when using the Wiley AI Gateway through Claude’s interface. You can see all queries and responses in JSON.

Here’s a simple prompt or query I sent to Claude with only the Wiley AI Gateway enabled:

You can see my prompt and Claude “thinking” and “deciding” to search for papers by calling the Scholar Gateway Search with what Claude calls a “semantic search”.

Even with minimum JSON familarity, you should be able to make out how my natural language query was translated—correctly limiting results from 2020 to 2025. It also retrieves the top 20 ranked results.

Under the Hood: RAG with Chunks

The Wiley team explained that what happens in the background is standard RAG: full text is chunked, and “semantic search” (dense embedding/retrieval) matches chunks to queries with reranking of the top 30 chunks. I was told they plan to add hybrid search (possibly BM25?) and/or knowledge graphs in the future.

This is backed up by the FAQ

Coverage wise it currently covers 3 million or so articles from Wiley, but there are plans to include other publishers content who partner with Wiley

Impressive Transparency on Search Quality

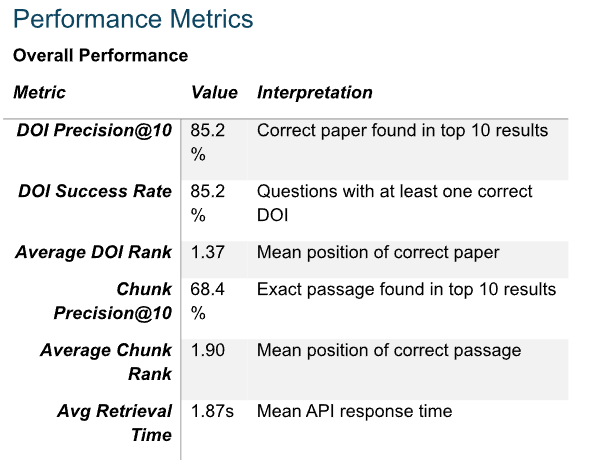

What really impressed me was Wiley’s willingness to share their evaluation metrics—and their permission for me to share some details publicly.

I am told they plan to be very transparent about how they measure quality, though they’re still finalising the exact format for disclosure. This is a bold and welcome step. We’ve always lacked this transparency from discovery vendors, and it raises the bar significantly. Given that Wiley AI Gateway is probably one of the first major academic MCP servers, hopefully it sets a standard for others.

Below is a small sniplets of what they shared with me.

Looking at their evaluations (based on 750 questions from their test set), the DOI precision@10 of 85.2% makes sense. This implies that if you search for a paper by DOI, there’s a roughly 15% chance the correct paper doesn’t appear in the top 10. In fact, one of my first tests failed to retrieve a paper by DOI, initially making me think the tool couldn’t handle DOI retrieval at all.

Chunk Precision@10 of 68.4% looks bad, but in the report they shared, they benchmarked against a leading dense embedding model (BGE-M3) which was only 8% better, so while there is some improvement to go, it is not terrible,

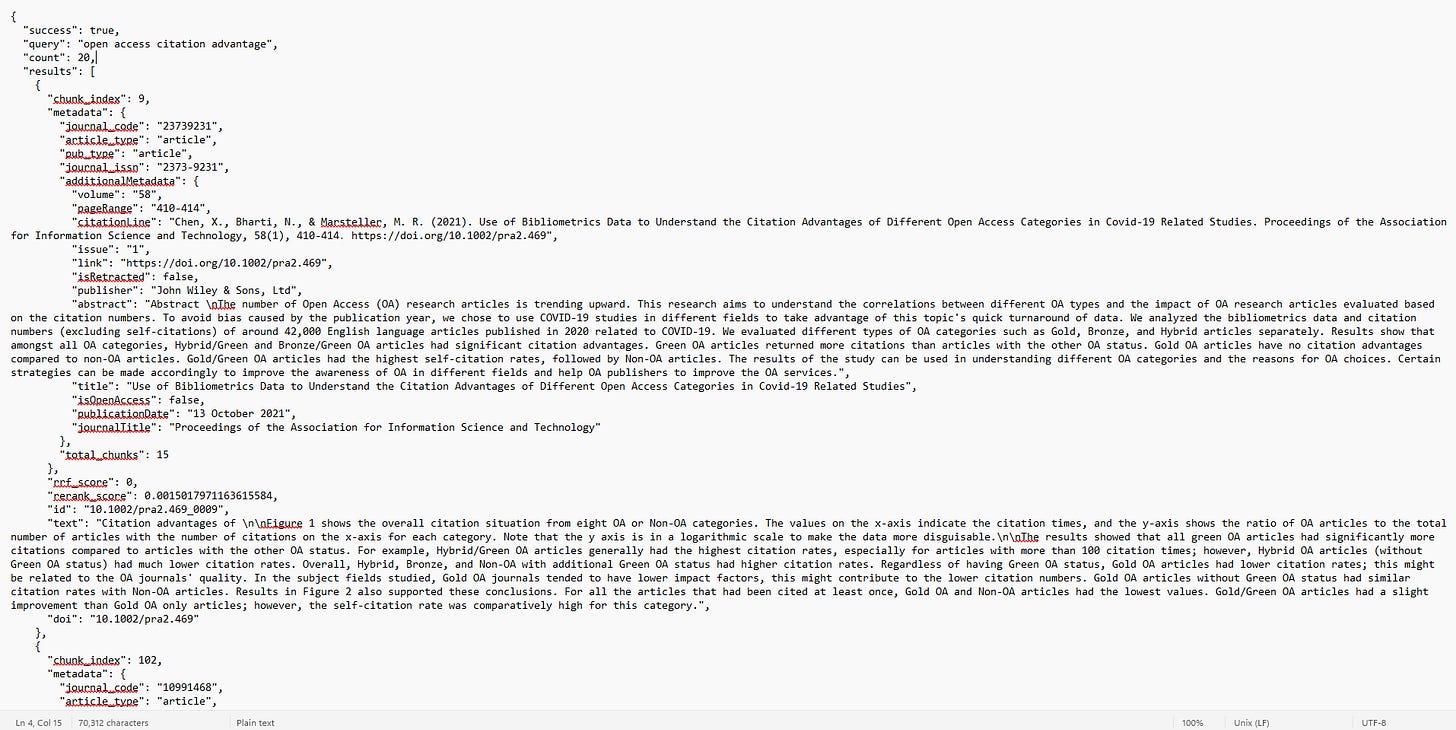

The Response Format

Responses come in JSON and are relatively easy to interpret. For a typical query, it retrieves 20 results. For each result, you can see:

Chunk number retrieved and the total number of chunks in the article

Metadata: article title, journal title, volume, issue, page, publication type, ISSN, publisher, abstract etc

Retraction status (important since LLMs often cite retracted works that are retrieved & one can filter retracted papers off - or perhaps the LLM given this information can use it in the generated answer), Open Access status

The actual text of the chunk

Relevance scores (rerank_score, rrf_score)

For the first result, you can see that it says it retrieved chunk 9 and various metadata of the article.

You can even see this article has 15 chunks in total and the text that makes up chunk 9.

The “id” field, is actually a combination of the article doi followed by _<chunknumber> which allows the LLM to combine chunks across the same article when needed.

Finally you can even see the final relevance score after reranking for each chunk “rerank_score”.

“rrf_score” probably stands for Reciprocal Rank Fusion, which is a way to calculate a combined rank based on multiple ranking scores. For example, a system which give a seperate score/ranking using BM25 and Dense embedding can use RRF to combine the two to get a “fused”/combined rank.

The “rrf_score” currently shows zero all the time because the system is just doing “Semantic search”, though hybrid search might be coming.

From there Claude will use the 20 retrieved chunks to try to answer my question which much like how RAG or retrieval augmented generation works.

Preliminary Observations of the Wiley AI Gateway

I spent considerable time exploring how inputs get translated into search queries. You’ll quickly discover that there are queries it can’t handle—either because the LLM translates it strangely or because the MCP server lacks certain capabilities.

For example, I asked it to look up a paper and show references from a certain year, but it reported it couldn’t access references via the MCP server. Another example: inspired by recent research, I found it generally struggled to find “the last sentence of a paper”. You would think since the metadata actually states the number of chunks in the article so in theory the last chunk (which usually excludes references) should be identifiable. That said, I suspect this MCP server has no way to request by chunk number. Opus 4.5 sometimes figures it out anyway but a lexical search instead of just a semantic search should easily nail this.

Requesting figures or tables generally works well.

This highlights an emerging challenge for natural language search interfaces: we lack affordances showing what’s possible (e.g. filters available). With agentic search, the range of possible tasks has expanded so dramatically that users don’t know what’s achievable and what isn’t. E.g. Can Claude use Wiley Connector to look up a paper, find related papers that are related and could have been cited but are not cited? Answer : With the Wiley Connector no because it can’t easily access the references to check.

Often, turning on the free web search connector solves issues—if an Open Access copy exists. For example, for the issue of finding the last sentence, or finding references of a certain range, the web search connector might be able to download a open access version of the paper and extract the answer from the whole paper’s full text overcoming the limitation of chunk based retrieval only.

Lots more testing needed!

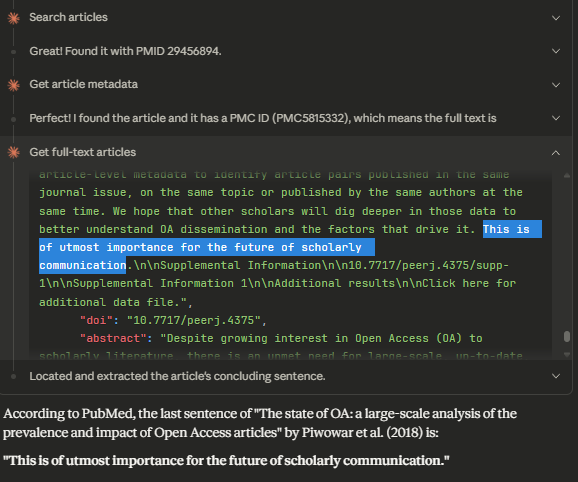

Testing the PubMed MCP Server

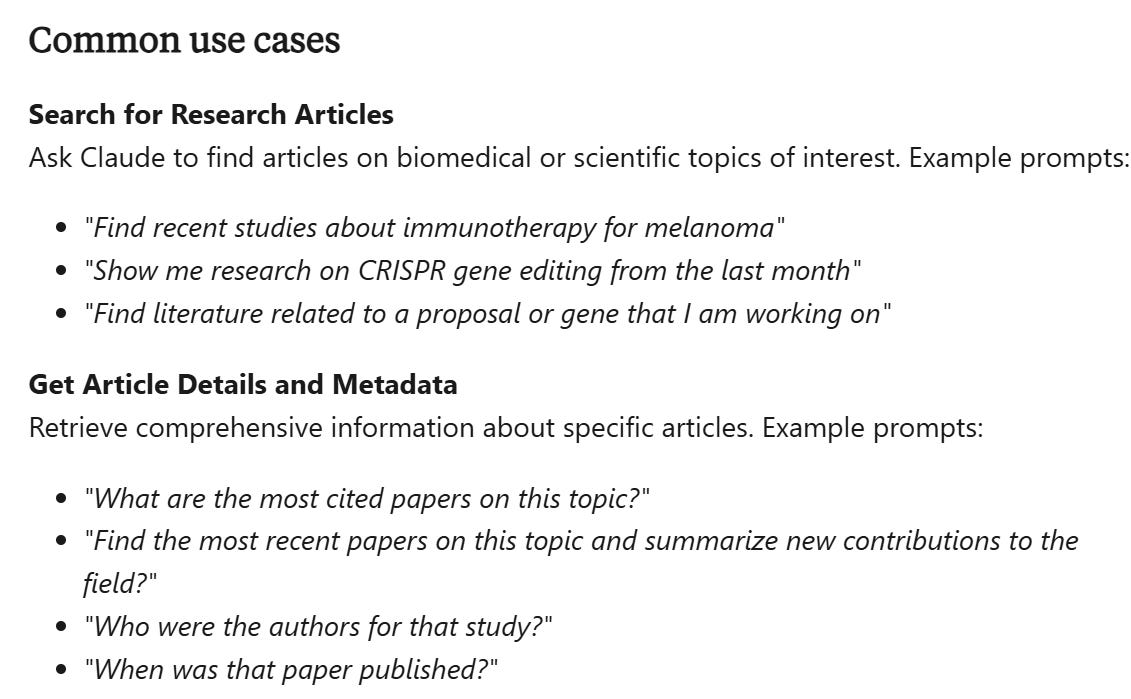

While exploring the Wiley AI Gateway, I discovered you could also enable a PubMed MCP server. It’s appears to be one offered by Anthropic, but unclear if NLM is involved.

There is of course some risks using MCP servers (either locally or remotely) by third parties since this involves running code in the background. But given this one seems officially offered by Anthropic it should be fine.

I used similar settings: extended thinking on, research mode off, web search off, only the PubMed connector enabled.

The PubMed MCP server works quite differently from Wiley’s.

One key difference: it displays the available tools, giving you a clearer idea of capabilities.

Secondly as you will see later, it actually uses the default PubMed search to retrieve results after which it can retrieve the complete full-text (not chunks) via PMC.

The document suggests the PubMed connector is quite capable of searching for “most cited papers” - though when I tested, Claude claimed “PubMed doesn’t directly provide citation counts in its search results”.

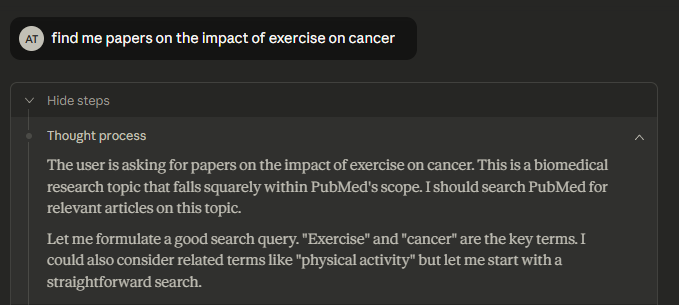

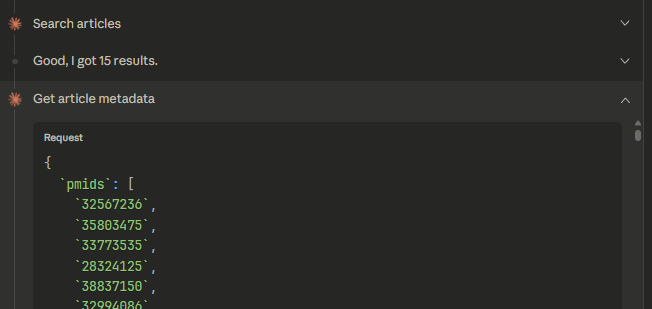

Lots of testing needed to see what this connector is capable of but for my first test searching for papers on impact of exercise on cancer, Claude was somewhat lazy—it went with the simplest possible query:

As you can see from the Json request below, it literally did the equalvant of entering in Pubmed

exercise cancer

and retrieved the top 15 results by PMID

This is the response.

It retrieved the top 15 results by PMID (see screencap below),

plus the total number of hits and query translation (presumably via Auto Term Mapping).

I confirmed this was working as expected by running the same query through PubMed’s web interface: I got 35,718 hits (one more than the MCP server for some odd reason). The top 15 PMIDs matched what I got sorting by “Best match” in this case, though I have seen it query with “most recent” sorting in some cases as well.

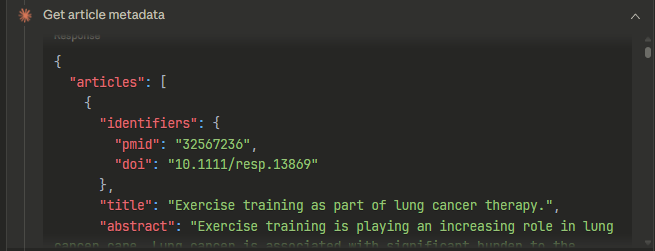

Claude then used those 15 PMIDs to request article metadata (title, abstract, etc.) and generated an answer from there.

This part of the response

So from there it uses the metadata including title and abstract to generate an answer.

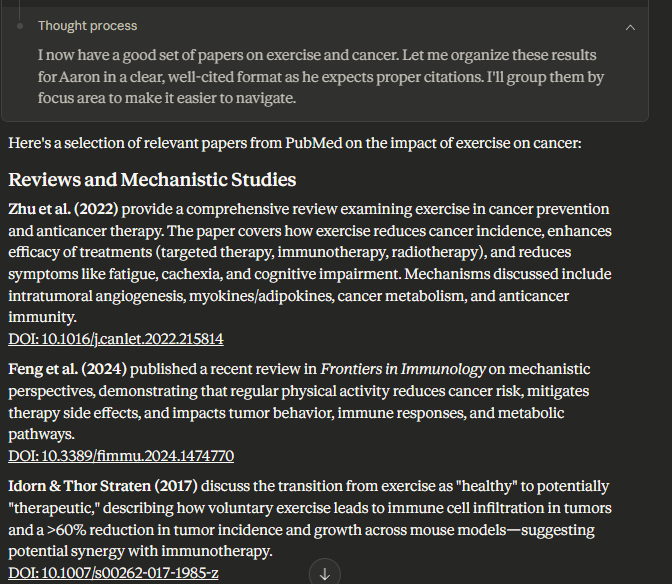

Retrieving full text vs text chunks

As you can see from the tool list, this Pubmed MCP server can also ask for full-text. But this is done only by feeding it PMIDs. Unlike the Wiley AI Gateway server (where you can get only chunks of text) you get the whole paper’s full-text (if available in PMC) in the response and not just chunks.

This is why it can more easily answer questions like “find me the last sentence of The state of OA: a large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles”

However, like Wiley, the full text here doesn’t include references, and the metadata lacks them entirely. Questions like “find me papers referenced by X from 2016–2017” remain tricky—though since you can get full text via PMC, the LLM can potentially download and use inline references to attempt an answer.

In comparison, Wiley AI Gateway only gives you chunks.

A Game-Changer: LLMs Can Now Pilot-Test Boolean Search Strategies

Since ChatGPT launched, evidence synthesis researchers have explored two main applications: using LLMs as screeners (promising but uneven results) and using them to generate Boolean search strings (largely unsuccessful).

Studies pitting librarians against ChatGPT on generating Boolean search queries such as this one, consistently showed humans generating strategies with far better recall, while LLMs tended toward higher precision but lower recall. More recent studies tried different prompting strategies and even fine-tuning—with no greater success.

I always felt these comparisons were unfair. Human searchers can look things up, check the MeSH browser, and pilot-test different strategies. LLMs could not.

Until now—via the PubMed MCP server

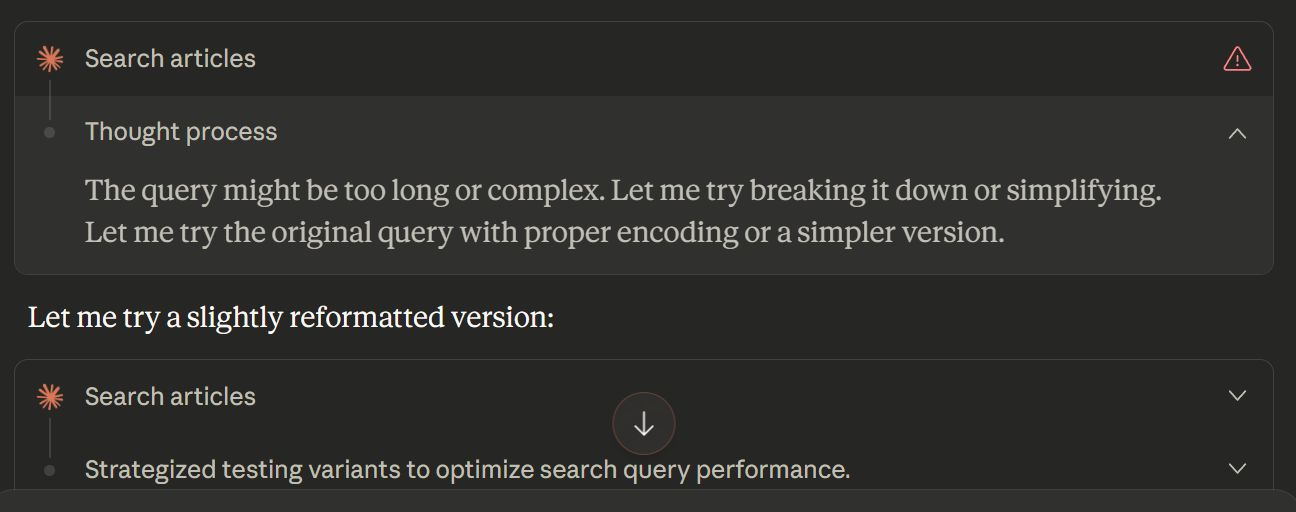

Note: The PubMed MCP server seems to have a bug that breaks with queries that are too long, forcing the LLM to test simpler versions. I’ll ignore this issue for now.

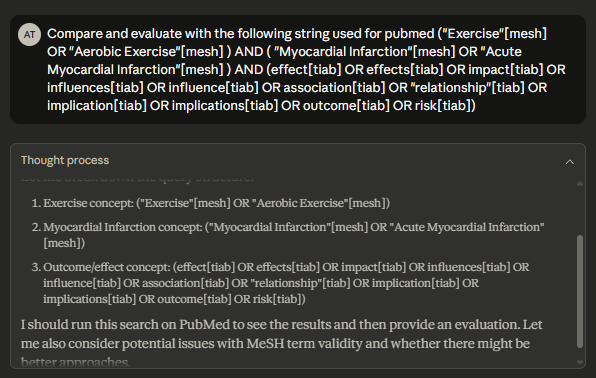

Example: Evaluating a Boolean Search Strategy

When I asked Claude to evaluate a Boolean search strategy, it:

Identified the main concept blocks

Ran the search to grab top-ranked 5 items by PMID and retrieve their metadata

Then it “notices” something

It decided to check whether MeSH headings existed and “wondered” whether to drop the outcome block (conventional wisdom in many cases)

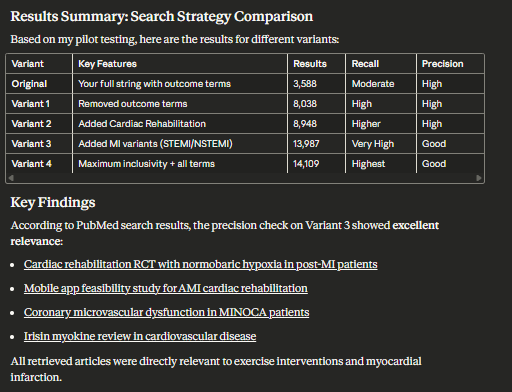

I won’t screencap every step, but here’s what it conclused.

Evidence synthesis experts might critique the specific choices of what to test and judgments made while thinking, but that misses the point: it is now capable of testing search strategies in PubMed!

In another run, it assessed precision by trying to find landmark papers and checking if the search retrieved them. For this, I will not screencap the JSON output and just show some highlights.

After testing it gives this

I am not sure the way it assesses precision is the right way to do it but in any case, I do see it test proposed search queries against known “landmark paper” to see if search finds it method.

I expect librarians who are good at piloting searches can do a much better evaluation of what it did than me so I won’t try to do it.

In the long run, I wonder if experts could “teach” it via example in prompts or even thedo finetuning to pilot test better?

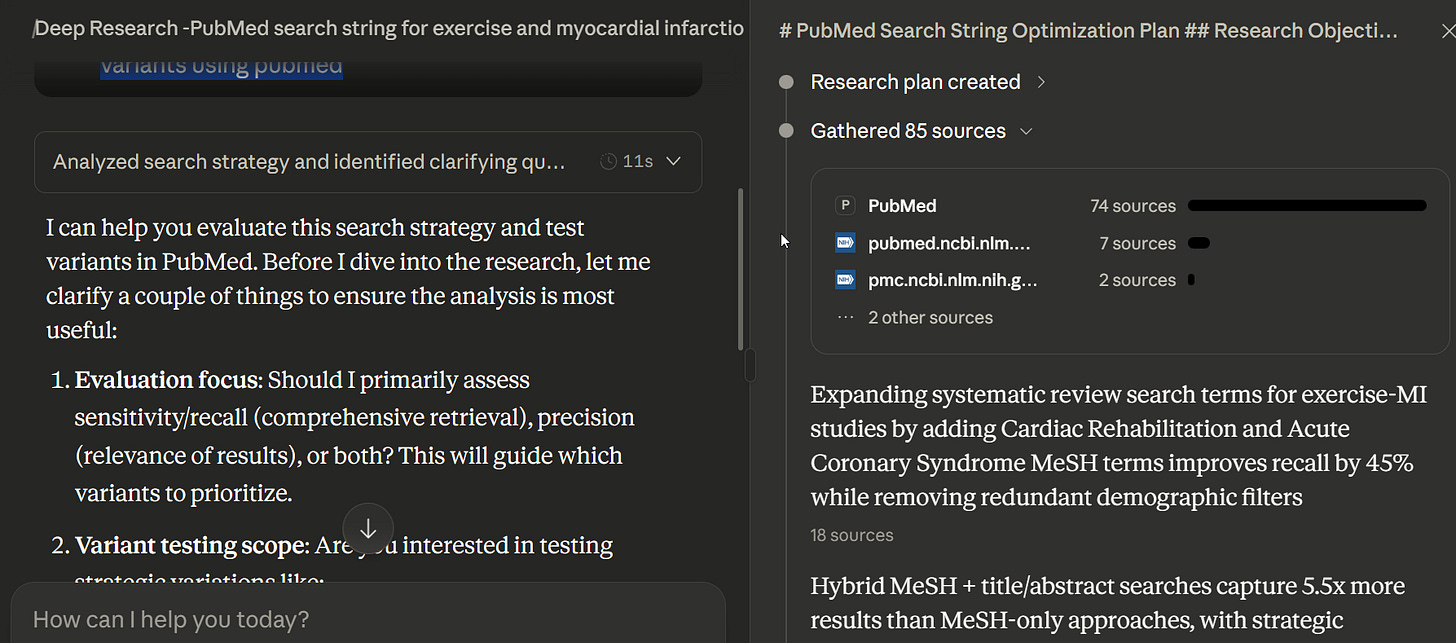

Using Deep research mode

With extended thinking enabled, results improve before it thinks longer. Turning on Deep Research mode (”research” in Claude) likely produces even more thorough testing—in one case involving deep research, it made 85 tool calls of “search article.”

That said in some runs it will decide that doing so is “overkill” and refuse to do it

The 2010s Parallel: We’ve Been Here Before

If the MCP architecture sounds familiar, that’s because it resembles something libraries tried two decades ago: federated search and eventually abandoned.

The Rise and Fall of Federation

Before Web Scale Discovery or Discovery layers in libraries, in the mid to late 2000s, if you wanted to search across multiple databases simultaneously, you used meta-search or federated search. A meta-search system would let you select a few database connectors, enter your query, and the system would translate it to appropriate syntax and send it to each database in real time. Responses would return to your federated search tool, which would combine and display results.

In practice, this led to slow responses, frequent errors when connectors broke, and terrible ranking. The ranking problem was particularly acute: metadata wasn’t uniform across sources, and reranking results arriving at different times from multiple sources proved nearly impossible. The technology was slow and unreliable and though many libraries employed it, it was never popular and libraries hungered for a “one-search” that worked better.

Web Scale Discovery Takes Over

In the early-to-mid 2010s, a new approach emerged: Web Scale Discovery. Products like ProQuest’s Summon, EBSCO Discovery Service, Ex Libris Primo (now under the same owner as ProQuest), and OCLC’s WorldCat Discovery raced to build large centralised indexes of academic content.

This was libraries’ attempt to match Google Scholar—providing a single search box over all academic content. Back then, people wondered: would publishers provide content to these discovery vendors?

Evidence mounted that opting out meant plummeting usage while competitors who opted in gained ground. Eventually, most content owners capitulated.

Still, the debate at the time in the early to mid 2010s was whether to “index when you can, federate when you must” (Ebsco Discovery Service) or just rely on centralized index alone (Summon service)—and centralised indexing as the only method won decisively.

By the mid 2010s even Ebsco Discovery Service stopped offering federated search because most journal publishers (even Elsevier) opted in to being indexed. As such the added value of federating the remaining content (e.g. newspapers, law databases) was too low to be worth the complexity to setup and maintain and most users didn’t want to wait anyway.

The story was actually had further nuances, especially the rivalry between ProQuest and EBSCO—both discovery vendors (Summon and EDS) AND content aggregators. This led to issues like reluctance to exchange metadata properly and problems linking to aggregator content when using a competitor’s discovery system.

The AI Search Index Problem

Today’s AI search tools face a similar challenge. Startups like Elicit, Consensus, and Undermind.ai rely on the Semantic Scholar Corpus and OpenAlex. Others like SciSpace and Scite have mostly scraped the open web. This limits full-text access to Open Access content and whatever publisher partnerships vendors can negotiate.

Generic deep research tools like OpenAI and Gemini Deep Research spin up virtual browsers to browse like humans, but they face the same limitations and cannot access paywalled content unless there is some mechanism to stop and allow users to sign in . While you can do this with OpenAI’s agent, I don’t see content owners being happy with allowing this

Some progress has been made—Scite, Consensus and even Semantic Scholar themselves have announced publisher partnerships. But they’re far from covering even the majority of publishers. Even Elsevier, despite having full-text access to their own content, holds only a minority of all academic full-text.

The only player sitting on a substantial crawled full-text corpus was Google Scholar—and until recently, they hadn’t used it for “AI”. The launch of Scholar Labs was a step forward, but focuses on finding papers rather than generating synthesised answers.

Another player I am curious are the winners of the last “Academic content war”, Ebsco and Clarivate (now owner of both Summon and Primo). Clarivate’s CDI (Central Discovery Index estimated at 5 billion records) is probably the only single source of academic content that can rival Google Scholar’s. I am unsure how much of it is full-text (CDI stores first 65k characters of text when available) but you can already see some publishers like Elsevier opt out from products like Primo/Summon Research Assistant

This month, I also heard about Elsevier’s LeapSpace, reportedly covering 15+ million peer-reviewed full-text articles not just from Elsevier’s ScienceDirect and Scopus products but also from other publishers. There was a previous product called ScienceDirect AI, but it seems all existing customers of that product will be transfered to LeapSpace, which suggests Elsevier hopes to go beyond just their own content.

Will anyone succeed in building comprehensive indexes? Will publishers cooperate as they did for Web Scale Discovery?

Implications of MCP Servers for Academic Content

I’ve been testing these MCP servers for a month and am still absorbing the implications - which probably can be a subject of many future posts. But here are my initial thoughts.

Will This Model Catch On?

MCP servers represent the federated approach: real-time queries to distributed content sources rather than centralised indexing. Last time, federation lost. But three things have changed:

Content owners are newly cautious. With intense concerns about AI training on copyrighted content, publishers are far less willing to hand over full text or even title abstracts for centralised indexing. MCP servers let them maintain control—content stays on their infrastructure.

The technology has matured. The problems that plagued old-school federation—slow responses, broken connectors, terrible ranking—are more tractable today. LLMs are remarkably capable of synthesising results from multiple sources with different metadata schemas. They can handle the “messy” reranking problem that defeated 2000s-era federated search.

User expectations have shifted. Federated search was unacceptably slow in 2010. But today’s users have been trained to wait longer by Deep Search/Deep Research tools that openly take minutes. A few extra seconds for MCP server calls is no longer a dealbreaker.

Still, for efficiency, systems will want to minimise MCP server calls. We might see content owners organising around large aggregate MCP servers—by publisher? By field?

Business Models

How will content owners price MCP access? Will it be tied to institutional subscriptions? Or decoupled entirely?

One model I’ve heard discussed mimics Spotify: searching incurs a nominal fee (per-search or per-chunk/token), with content owners paid based on usage. Full-text access would be charged separately. This could appeal to those who want to pay only for what they use rather than subscribing to bundles.

I can already hear librarians grumbling about publishers finding yet another way to monetise the same content. But imagine a model where you no longer subscribe to big bundles of journals and only pay for what your users use.

See more discussion on business models here.

Impact on discovery vendors

If MCP-based content access catches on, this could be both a opportunity and threat to early AI discovery vendors like Elicit and Consensus.

They could use MCP servers to supplement their existing indexes (unclear about the buiness model), but once it becomes common for major LLM platforms (ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, DeepSeek, etc or even open weight models) to allow direct academic content access via MCP, the reason to use specialised academic tools diminishes. Many users will prefer sticking with tools they already know.

In terms of effectiveness, if MCP servers are the major way in which content is retrieved, this makes Discovery products and agents more reliant on the sophistication of the retrieval step built-in by the MCP server.

As we have seen, the Wiley AI Gateway server has a couple of quirks and a discovery vendor like Elicit or Undermind or Scite.ai using it would be subject to the limitations of what the Wiley AI Gatewat can retrieve as opposed to designing their own retrieval mechanism for content that is indexed centrally.

For Librarians

Understanding information retrieval at a technical level becomes even more important as we evaluate these tools. The transparency Wiley has committed to is encouraging—I hope it sets a standard.

The most exciting development is the new capability for Boolean search strategy testing. For the last 3 years, we’ve found that LLMs couldn’t match human expert searchers at generating systematic review searches. Now the comparison changes. The question isn’t whether Claude can generate a perfect search string from scratch—it’s whether Claude can help refine, test, and improve strategies that human experts develop.

Conclusion

MCP represents a potential paradigm shift in how AI accesses academic content. Rather than the centralised index model that dominated Web Scale Discovery, we may be entering an era of AI-native federated search—with better technology, greater transparency, and new business models.

The parallels to the 2000s are instructive but not determinative. The incentives have shifted, the technology has improved, and user patience has grown. Whether MCP-based access becomes the dominant model or supplements centralised indexes remains to be seen.

I’ll continue testing and will share more findings in future posts. Have you experimented with MCP servers for academic search? I’d love to hear your experiences.