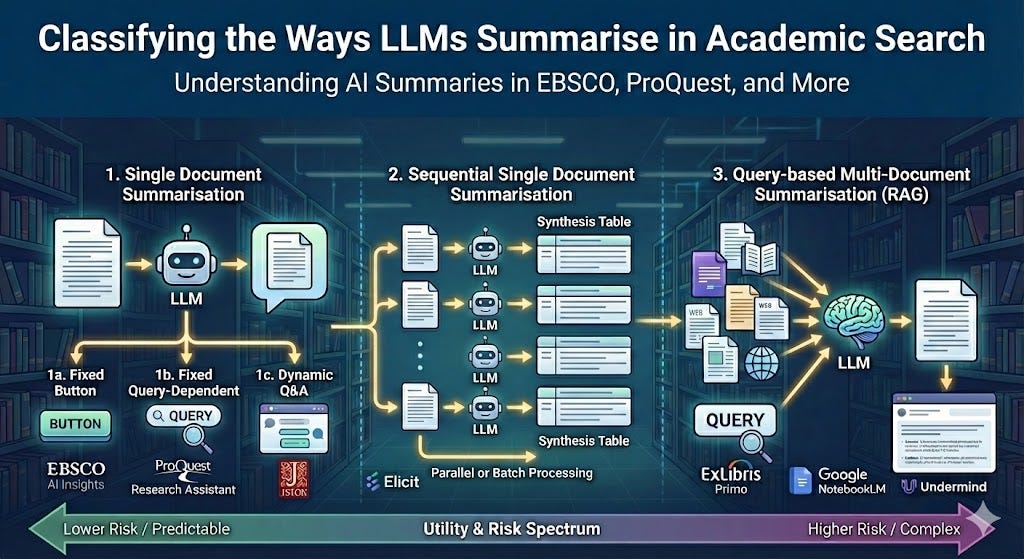

Classifying the Ways LLMs Summarise in Academic Search

Understanding AI Summaries in EBSCO, ProQuest, and More

I’ve focused mainly on understanding retrieval for the past few months, e.g., classifying Academic search into the “4 Quadrants of Search” and distinguishing between truly “agentic” systems and more predefined workflows.

But retrieval is just one part of the equation. LLMs and GenAI are also impacting search through their ability to extract and summarise text1.

Regular readers are familiar with how “naive” Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) works: it uses retrieval to find relevant content and then uses the generative capabilities of LLMs to summarise it2. But there’s considerably more nuance to how summarisation is deployed across academic search products.

In this post, I’ll distinguish between the different ways LLMs summarise in academic search and what the implications are for evaluation and trust.

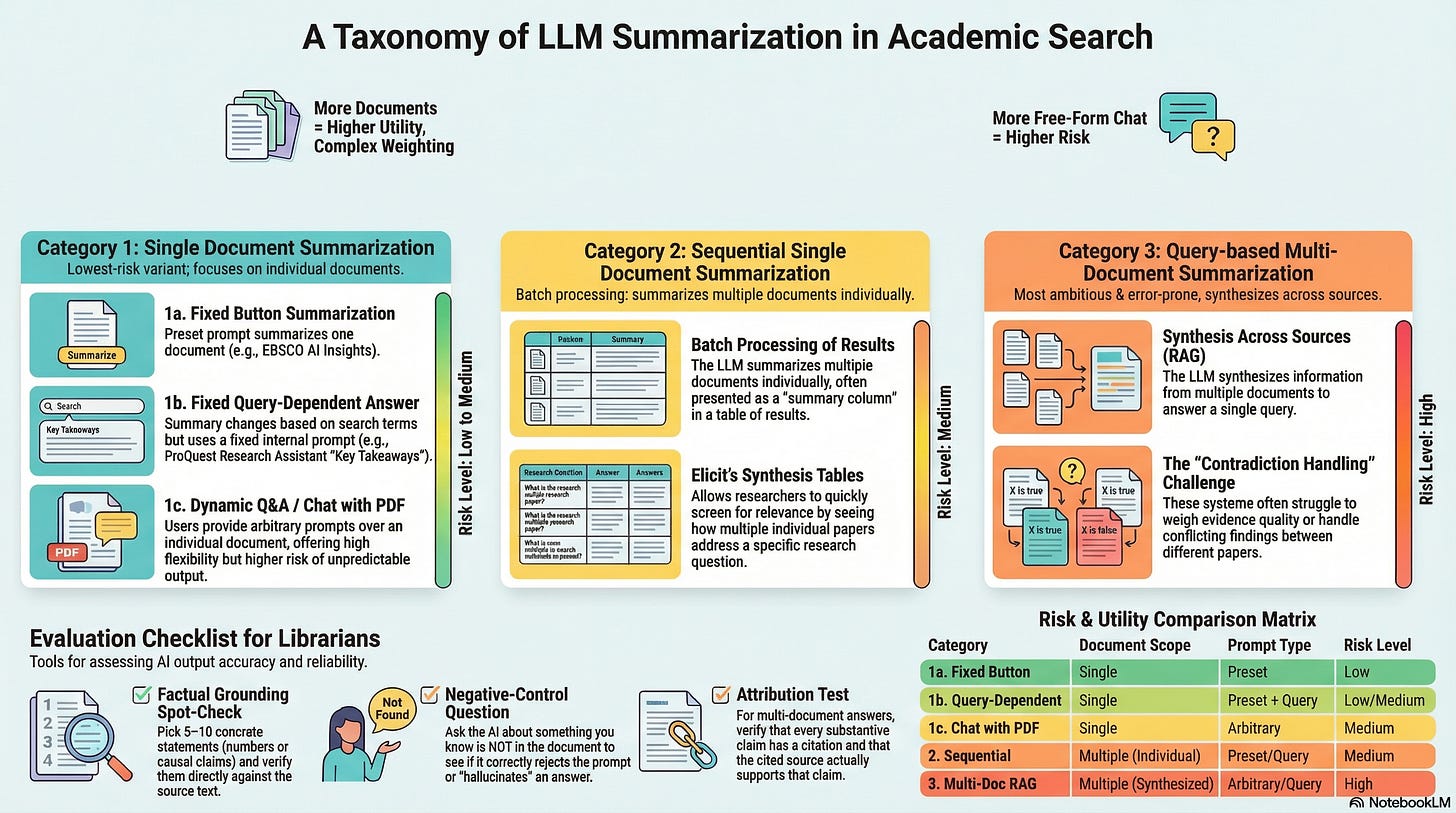

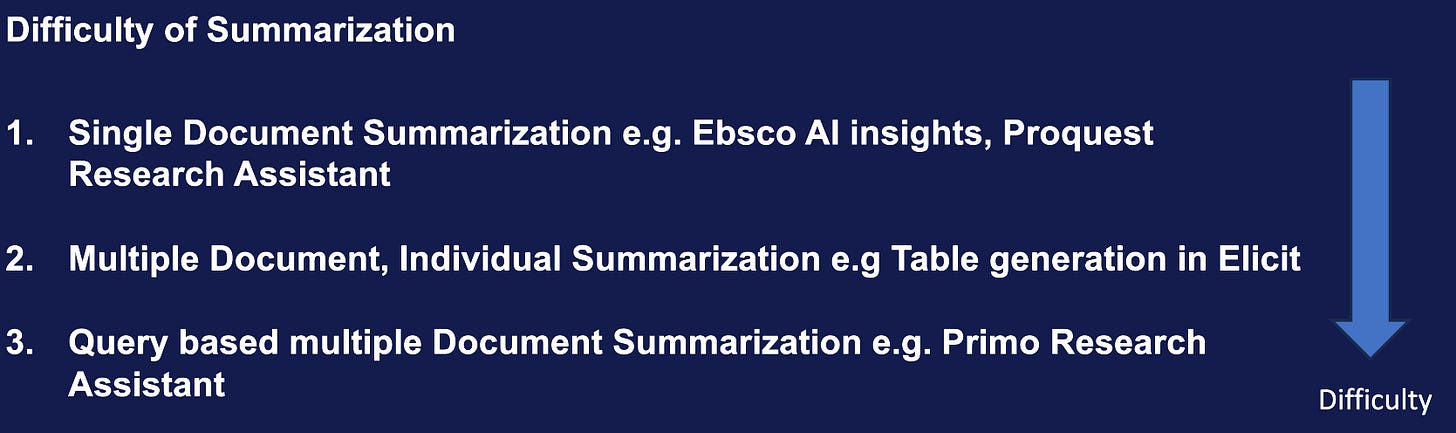

A Taxonomy of LLM Summarisation in Academic Search

After examining various academic search products, here is how I categorise them3:

Single Document Summarisation — LLM summarises one document at a time

Sequential Single Document Summarisation — LLM summarises multiple documents individually (e.g., synthesis tables)

Query-based Multi-Document Summarisation — LLM synthesises across multiple documents to answer a query (e.g., RAG)

I’m classifying by (1) how many documents the model is allowed to use at once, and (2) how much the user/query can change the prompt. Those two knobs largely determine utility, risk, and how testable the feature is.

Utility tends to increase as the model is allowed to use more documents and answer more specific questions. Risk increases when you combine broader scope with more prompt freedom and harder reasoning (especially evidence weighting and contradiction handling).

1. Single document generation (fixed → query-conditioned → free-form)

Single Document Summarisation is straightforward: you use an LLM to summarise an individual document. However, there are three distinct variants worth distinguishing:

1a. Fixed Button Summarisation — A preset prompt summarises the document

1b. Fixed Query-Dependent Answer4 — A preset prompt incorporates your search query into the document

1c. Dynamic Q&A / Chat with PDF — You provide arbitrary prompts over the individual document

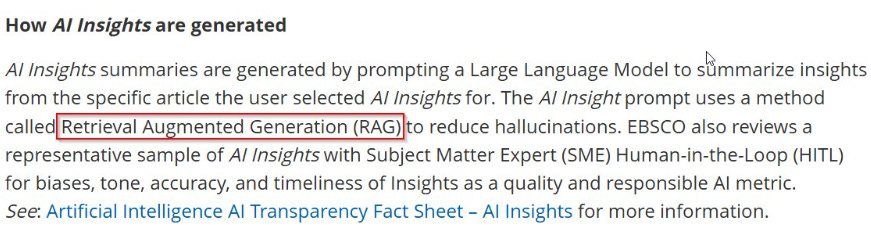

While you might expect these systems to feed entire documents to an LLM, most academic implementations—including EBSCO AI Insights and ProQuest Research Assistant—use RAG internally.

How Proquest Research Assistant generates key takeaways and concepts

If you see supporting snippets shown alongside generated statements, the system is a signal it is using RAG rather than processing the full document directly.

1a. Fixed Button Summarisation

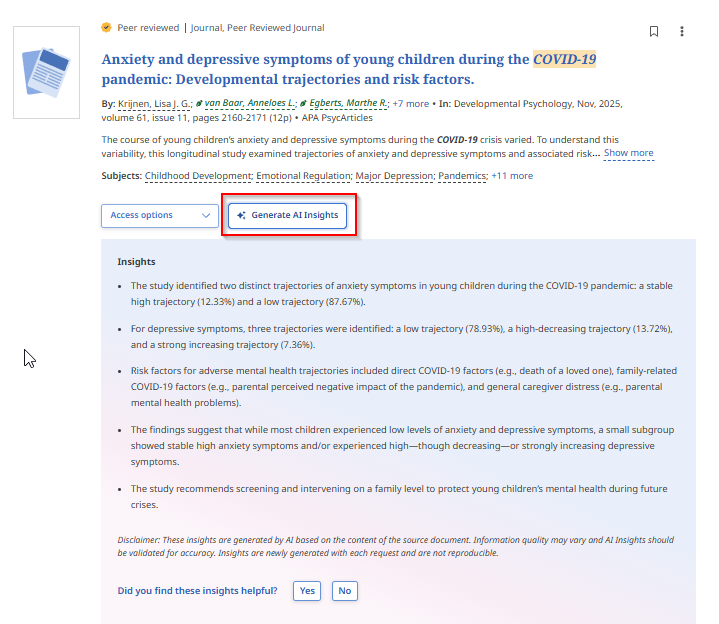

The simplest form: you click a button, a fixed prompt is sent, and a summary appears. EBSCO’s AI Insights exemplifies this approach.

EBSCO AI Insights explains it this way:

When the AI Insight button is clicked, a prompt is sent to a Large Language Model (LLM) prompting the AI to summarize the full text article into 2-5 relevant insights into the article. We ground the AI response on the full text (with publisher permission) to reduce hallucinations. No AI training is done on the full text article. The user query is not used in AI Insights.

This is probably the lowest-risk summarisation feature because everything is predictable with the least variables: the prompt is fixed, the document is known, and the vendor can test quality systematically before deployment. Ex Libris’s Document Insights in Primo uses a similar approach.

Questions to ask vendors:

Is full text used, or just the abstract? For ebooks, is it summarising a chapter or the entire book?

Is the system text-only, or can it process images and figures?

How do you test the accuracy of these summarisations and do you have benchmarks publicly available?

How deterministic is the output? Given a fixed prompt over a fixed document, why not pre-generate and cache summaries?

On that last point: pre-generation would save compute and ensure consistency, but I suspect most vendors avoid this for IP reasons. That said, the FAQ for Ebook Central Research Assistant notes it will “generate the same response for each chapter, regardless of who the user is or when they submit the prompt.”

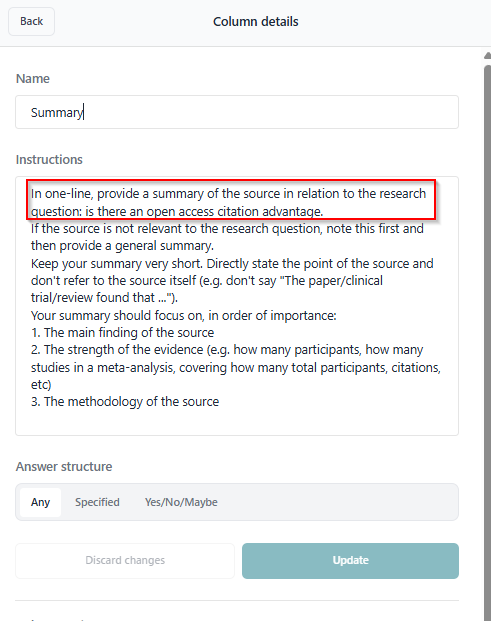

1b. Fixed Query-Dependent Answer

This variant is also “fixed” in that you cannot type arbitrary input—but the preset prompt incorporates your search query.

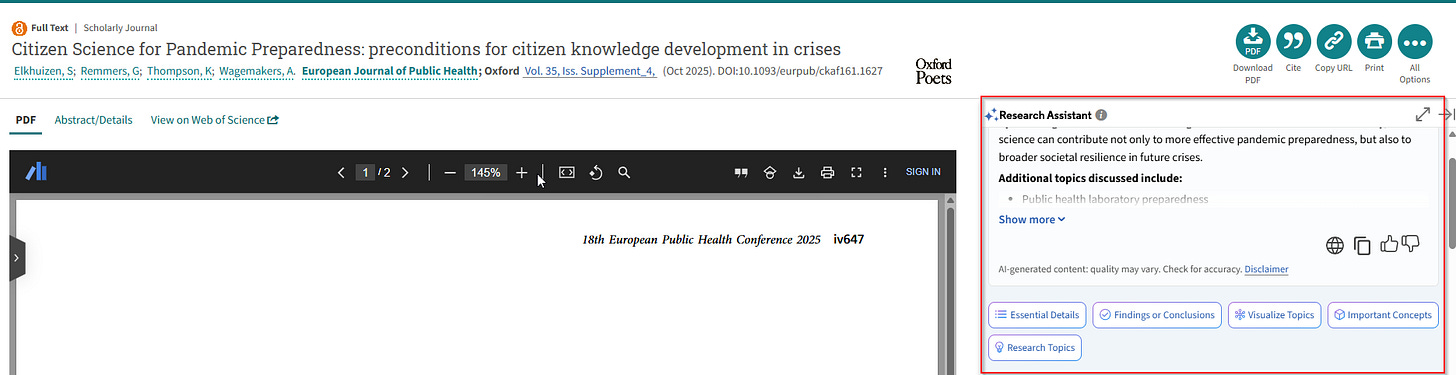

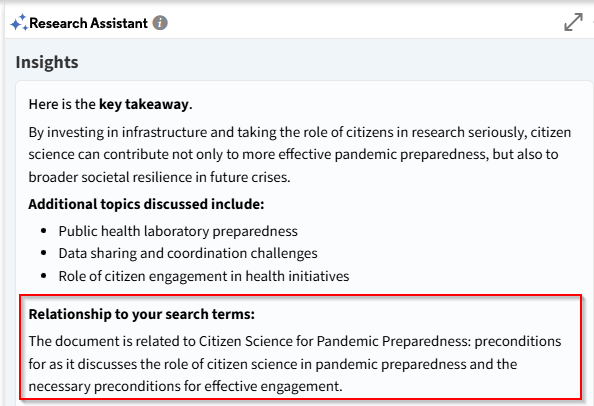

ProQuest Research Assistant demonstrates this well. When you click on an article, a sidebar automatically generates “Key Takeaways” along with options for Essential Details, Findings or Conclusions, Important Concepts, and more.

Most of these features match 1a, except for one crucial difference: the “Relationship to your search terms” section in the auto-generated “Key Takeaways”. This means even with deterministic generation, results vary depending on the query used to find the paper.

I first encountered query-dependent answers in an older beta of JSTOR’s Research Tool, which automatically generated text explaining

How is <query> related to this text

In my view, this feature deserves wider adoption, particularly when paired with “Semantic/Embedding Search”. It directly addresses the “semantic search always gives you something” problem—warning users that even if the system retrieved top-K documents, they might not actually be relevant to the specific question.

Compared to fixed single document summarisation, being query dependent makes the result a bit more unpredictable, but it is likely it is still much easier to test and tune for compared to the next method.

Questions to ask vendors:

Same questions as in 1a

How is query incorporated? What prompts are used?

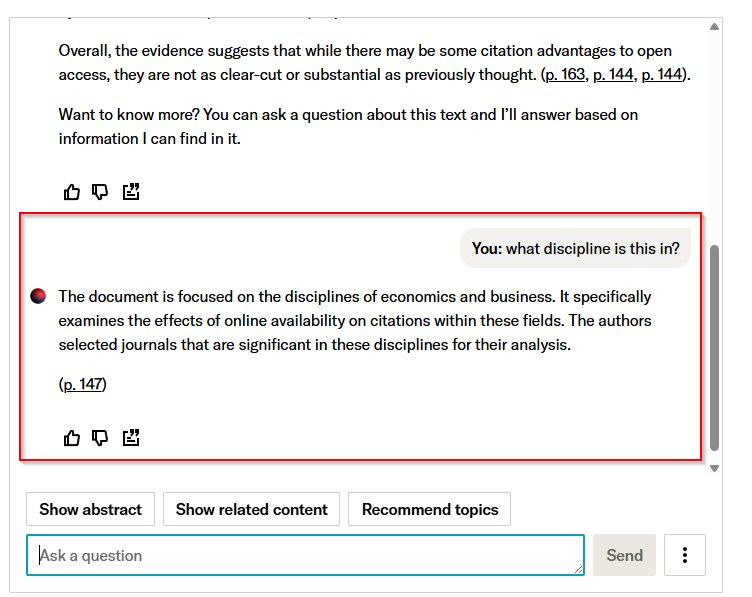

1c. Dynamic Q&A / Chat with PDF

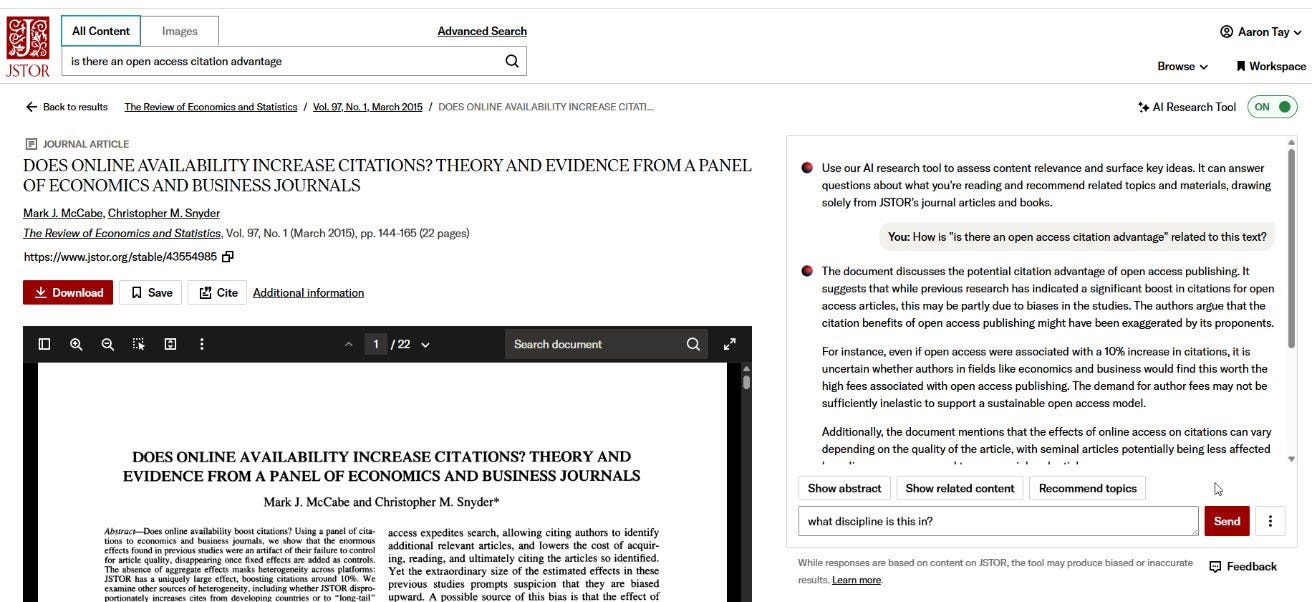

Unlike the fixed button-based approaches, here users type arbitrary queries into a chatbot-style interface. This “Chat with PDF” pattern has spawned numerous startups, though the value proposition as a standalone product remains unclear given that major platforms are integrating similar functionality directly.

In academic search, this feature appears in most AI-powered systems, particularly those from startups. JSTOR Research Tool (beta) includes this capability.

The risk profile is notably higher than fixed approaches: vendors cannot predict user input, making output quality inherently less predictable and harder to test comprehensively.

Questions to ask vendors:

Same questions as in 1a

What types of prompts/queries are expected to work and NOT work?

2. Sequential Single Document Summarisation

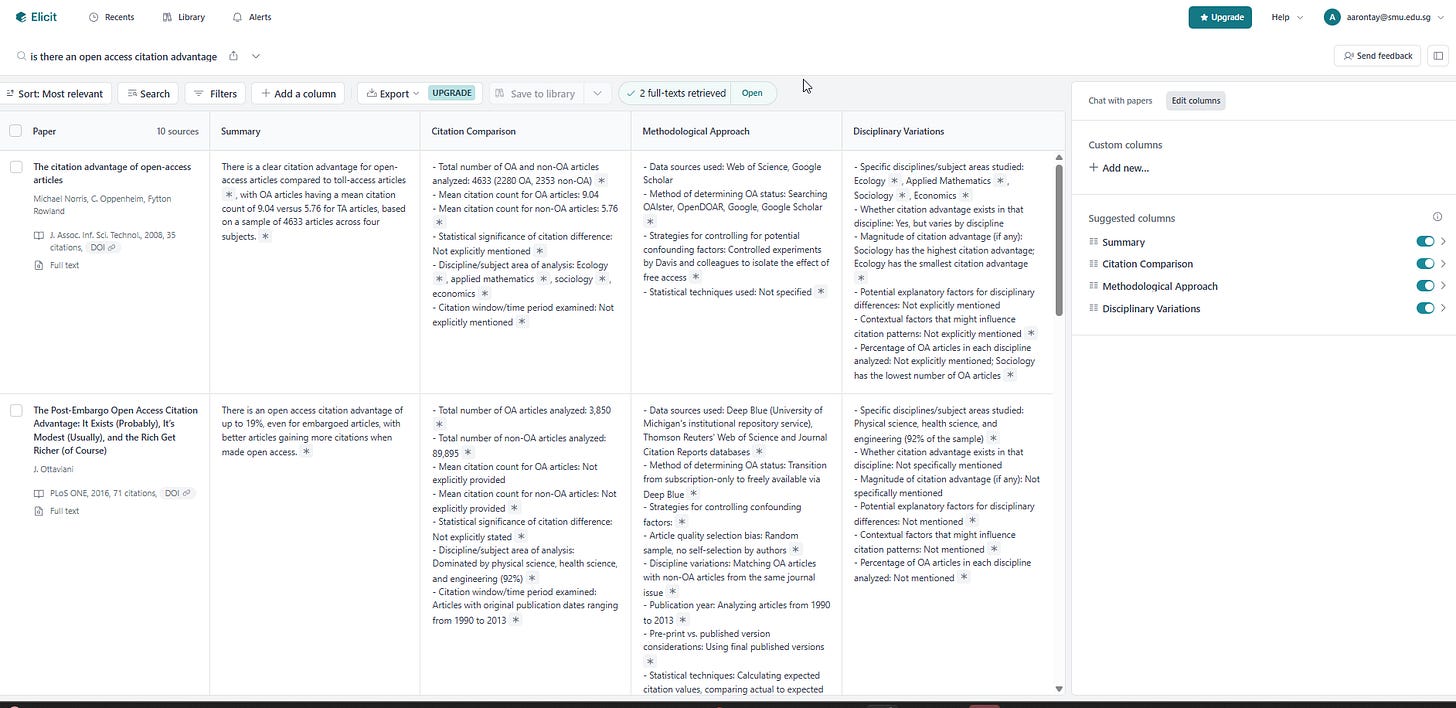

This method still summarises document-by-document but processes multiple documents in sequence or batch. Elicit.com pioneered this approach in commercial academic search.

The workflow: Elicit finds relevant papers and auto-generates a “summary” column for each. Users can add custom columns, and the LLM extracts or summarises from each paper individually to populate them.

The auto-generated summary column serves a useful secondary purpose—it acts as a relevance indicator. Because the summary instruction is query-dependent (e.g., “In one line, provide a summary of the source in relation to the research question: is there an open access citation advantage”), irrelevant retrievals become obvious when the summary cannot address the query.

This is essentially ProQuest Research Assistant’s “Relationship to your search terms” applied systematically across all retrieved results.

Variants Within This Category

Sequential summarisation has its own meaningful distinctions:

Parallel vs. sequential processing — Are documents processed simultaneously or one after another? This affects both speed and potential for cross-contamination of context.

Batch size considerations — How many documents can be processed together? Elicit and similar tools typically work with the top-K retrieved results.

Extraction vs. summarisation — Some columns extract specific data points (study design, sample size) while others summarise. Extraction is generally more reliable.

This category holds particular promise for evidence synthesis workflows. For extracting well-defined variables from structured research papers, LLM-assisted extraction can significantly accelerate systematic reviews—though human verification remains essential for anything beyond preliminary screening.

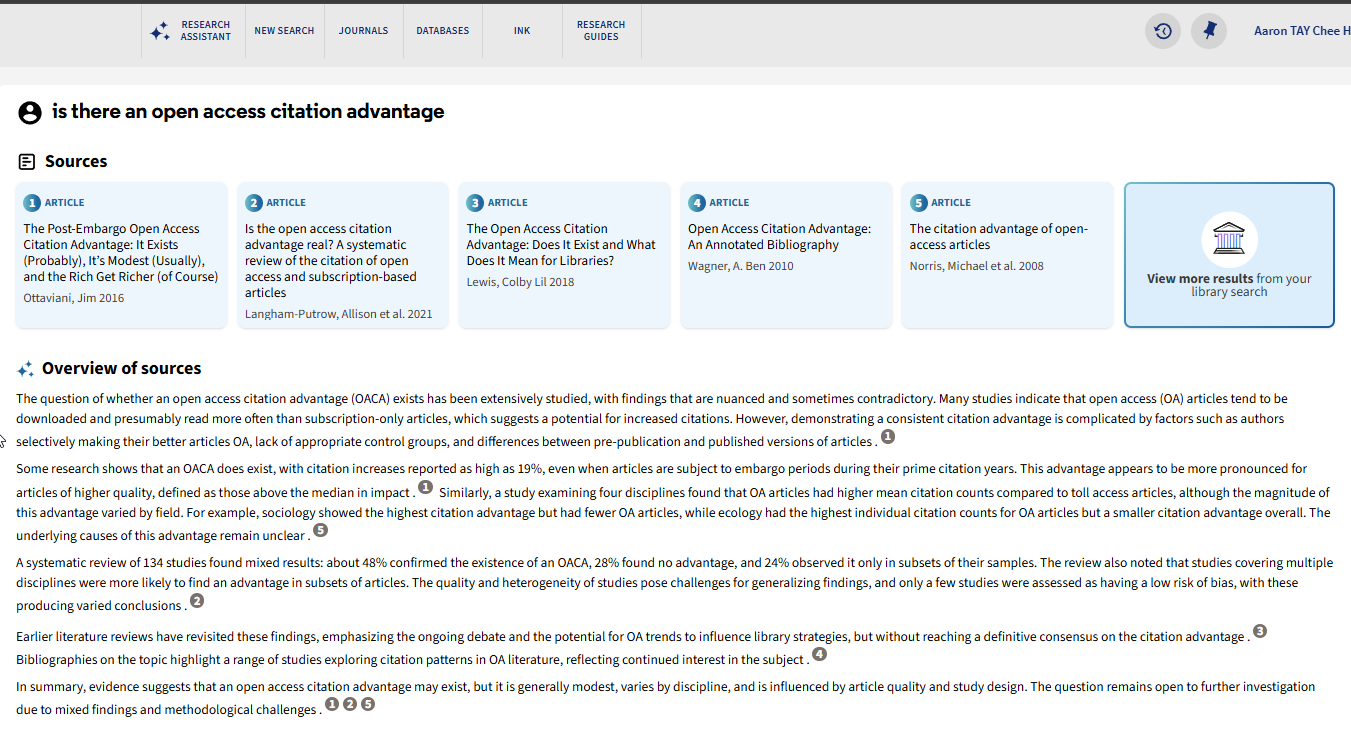

3. Query-based Multi-Document Summarisation

This is the most ambitious and most error-prone category: the LLM takes multiple documents and synthesises them to answer a single query. This is technically known as Query-based Multi-Document Summarisation, with RAG being the most common implementation.

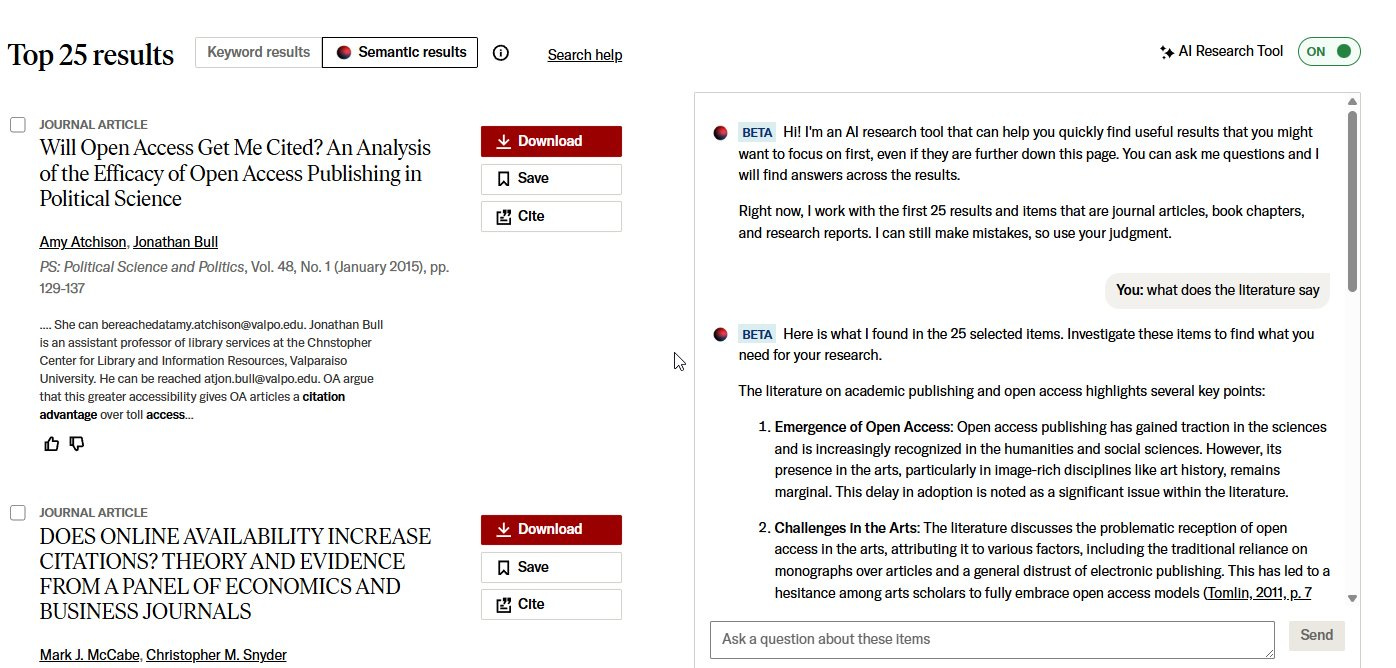

Ex Libris’s Primo Research Assistant exemplifies this approach, as do many other current products.

Variants and Hybrid Approaches

You’re not limited to documents from search results. Query-based multi-document summarisation can operate over:

Search results only — The standard RAG pattern

User-provided documents only — e.g., Google NotebookLM

Hybrid: search results plus uploads — e.g., Elicit Systematic Review, NotebookLM with search enabled

Another variant involves using your initial query to retrieve a fixed set of results, then allowing follow-up questions over that same corpus.

JSTOR Research Tool (beta) retrieves the top 25 results for your query, which then serve as the knowledge base for subsequent questions.

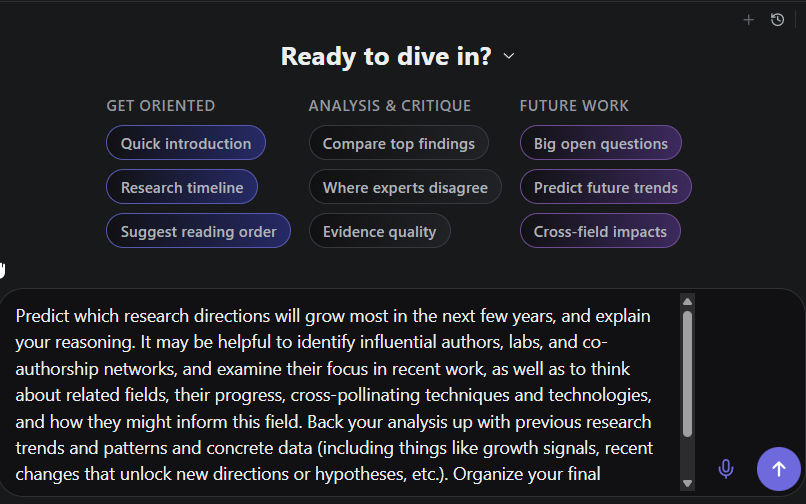

Undermind.ai’s “Ask Expert” feature takes a different approach: after its iterative Deep Research process identifies relevant papers, you can ask follow-up questions.

Notably, for questions like “Predict future trends,” the system can search the general web in addition to the papers already found in the academic corpus (Semantic Scholar)—a sensible design choice since trend prediction often requires non-academic sources.

Why Multi-Document Summarisation Is Hard

This category is difficult for at least three compounding reasons:

Retrieval quality — You need the right, relevant documents. Without them, nothing downstream works.

Accurate contextual summarisation — Each document must be summarised correctly in relation to the query. Errors here propagate into the synthesis.

Evidence assessment and contradiction handling — This is arguably the hardest problem. How do you correctly assess the quality and strength of evidence across documents, particularly when they contradict each other? LLMs tend to be credulous—they treat retrieved content as equally authoritative regardless of study design, sample size, or methodological rigour. This is improving with stronger models, but remains a fundamental limitation.

There has been worry about RAG-enabled LLMs happily citing retracted work. To be fair, humans do this too. The solution requires ensuring LLMs have access to updated indexes with retraction information (or perform real-time checks) and that models understand what retraction status means.

Evaluating Summarisation Quality

A taxonomy is only useful if it helps us assess tools. Here’s the uncomfortable truth: robust evaluation of LLM summarisation remains an unsolved problem, and the difficulty scales with each category.

Five practical checks Librarians can try

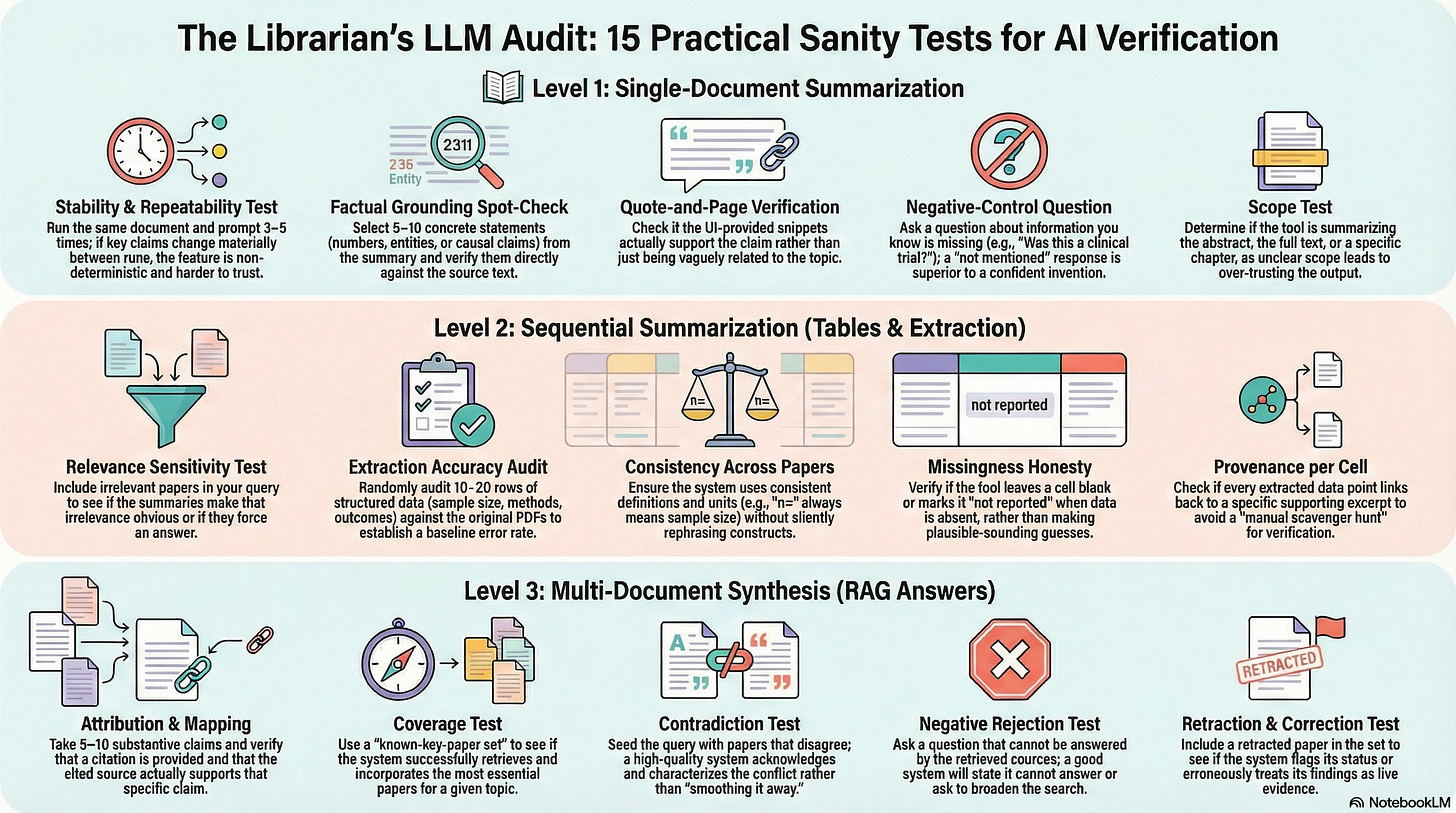

Robust evaluation of LLM summarisation is still an active research area5. But librarians don’t need perfect metrics to run useful, repeatable checks. Here are five practical “sanity tests” for each category—lightweight enough to do routinely, but strong enough to surface the common failure modes.

Tip 1: Because these systems are often non-deterministic you should consider running each test 3-5 times each!

Category 1: Single-document summarisation (1a / 1b / 1c)

Stability / repeatability test

Run the same document + same button/prompt 3–5 times. If key claims change materially between runs, treat the feature as inherently non-deterministic and harder to trust.Factual grounding spot-check

Pick 5–10 concrete statements from the output (numbers, causal claims, named entities, “the study found…”). Verify each directly against the source text.Quote-and-page verification

For each key claim, ask: can a user find the supporting passage quickly? If the UI provides snippets, check whether they actually support the claim (not just vaguely relate).Negative-control question (especially for 1c)

Ask something you know is not in the document (“Does this paper report a randomized controlled trial?” when it doesn’t). The best behaviour is “not mentioned / not in the source,” not confident invention.Scope test

Check what’s being summarised: abstract-only vs full text; for ebooks, chapter vs entire book. If scope is unclear, outputs are hard to interpret and easy to over-trust.

Category 2: Sequential single-document summarisation (synthesis tables / extraction columns)

Relevance sensitivity test

Use a query where only some retrieved papers are truly relevant. See whether the per-paper summaries make irrelevance obvious (e.g., summaries that can’t answer the question should look “off”).Extraction accuracy audit (sample-based)

For any structured column (sample size, method, population, outcome), randomly audit 10–20 rows against the PDFs. Report an error rate; this becomes your baseline.Consistency across papers

Check whether the system uses consistent definitions and units across rows (e.g., “n=” always means sample size; outcomes aren’t silently rephrased into different constructs).Missingness honesty

When information is absent or unclear in a paper, does the tool leave it blank / mark “not reported,” or does it fill with plausible-sounding guesses?Provenance per cell

For each extracted/summarised cell, can the system show the supporting excerpt? If not, every table becomes a manual scavenger hunt (and a trust sink).

Category 3: Query-based multi-document summarisation (RAG answers / synthesis across papers)

Attribution test (claim → source mapping)

Take 5–10 substantive claims in the answer. For each, verify that (a) a citation is provided, and (b) the cited source actually supports the claim.Coverage test (known-key-paper set)

Use a question where you know the “must-cite” papers. Does the system retrieve and use them?Contradiction test

Deliberately use a topic with well-known conflicting results (or seed a small set of papers with disagreement). Check whether the answer acknowledges disagreement and characterises it accurately, rather than smoothing it away6.“Not in the sources” also known as negative rejection test

Ask a question that cannot be answered from the retrieved set. Good systems will say so, ask to broaden retrieval, or qualify strongly—not hallucinate7.Retraction / correction test

Seed a retracted paper (or a paper with an expression of concern) alongside later work. Check whether the system flags status appropriately and avoids treating retracted findings as live evidence8.

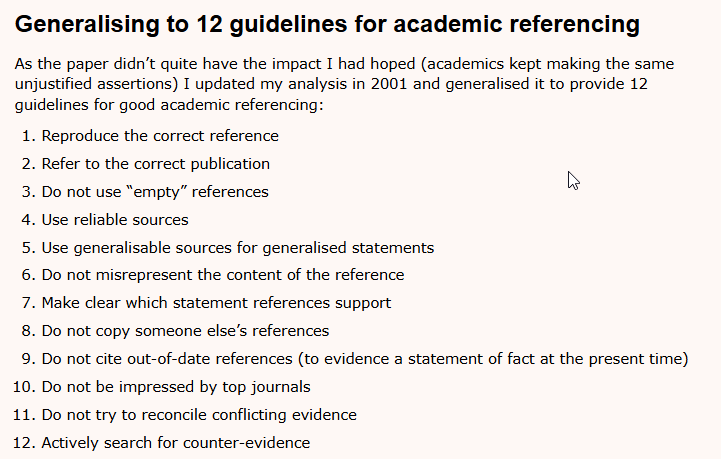

An alternative idea, I have been toying with is formally adapting Harzing’s 12 guidelines for academic referencing (last updated in 2001 which was designed purely for humans) as a standard to assess RAG output.

Tip 2 : Traditionally, LLMs have a strong bias to answer even when they shouldn’t, as such, if you have time for only one test, it is worth testing how they react to “null answers or results” to check for false positives/hallucations - basically 1.4, 2.1, 2.4, 3.4

Tip 3 : Take note of examples or scenarios where these tools fail. It is highly likely these are good scenarios to reuse.

Conclusion

Not all “summaries” are created equal. Treating AI summarisation as a monolithic capability is a mistake. There is a world of difference between a pre-canned summary of a single article (Fixed Button) and a dynamic synthesis of conflicting claims across twenty papers (Query-based Multi-Document Summarisation).

For librarians and researchers, understanding this taxonomy is crucial for information literacy instruction and tool evaluation. A fixed, single-document summary is relatively safe but limited—essentially a glorified abstract. As we move into dynamic, multi-document RAG, utility increases substantially, but so does complexity and error potential.

There is also a distinction between extractive summarisation (selecting and copying verbatim sentences from the source) and abstractive summarisation (generating novel text that paraphrases and synthesises). With LLMs, abstractive summarisation is now the dominant approach.

Not all features mentioned are generated directly with LLMs. For example, the generated mindmaps from “Visualise Topics” in ProQuest Research Assistant likely use the LLM to call traditional clustering tools rather than generating visualisations directly.

Deep Research mostly combines category 3 with iterative retrieval and self-checking—future post

This is an “answer” rather than “summarization” because this is generated in response to user’s search query

I have a series of blog posts in my draft on this complicated topic!

Should the generated answer “play favourites” and suggest certain papers are more prestigious and hence the claims should be taken more seriously? Or should they be even handed just addressing the claims in each paper equally?

This is traditionally the hardest test for RAG systems to pass. Worth trying!

This is often highly dependent on the the source - whether it has up-to-date information about retraction status and whether it is fed to the LLM.