Deep Research, Shallow Agency: What Academic Deep Research Can and Can't Do

The Agentic Illusion: Most Academic Deep Research run fixed workflows and stumble when given unfamilar literature review tasks that do not fit them.

Introduction

When AI academic search tools promise “research agents” and “AI assistants,” do we know exactly are they offering? What types of literature review tasks do these “agents” and “assistants” support? Are they able to reason flexibly, use the tools at their disposal to accomplish tasks like human research assistants?

I ran a simple test—asking tools to find papers that should have been cited by a given article but weren’t—and discovered something revealing: most fail completely.

Why do “agents” or “Research Assistants” fail such a simple task?

In short, we find that while today’s Academic Deep Re/search tools are impressive—they are mostly workflow-bound, not fully autonomous agents. They are closer to systems that execute pre-built scripts with AI decision points—not use human-level reasoning to flexibly achieve the goal.

So yes, these are agents in a technical sense. But calling them “research assistants” or “agentic” systems risks misrepresenting their limitations—especially for novel or off-template tasks not covered by the default workflows.

The Definition Problem

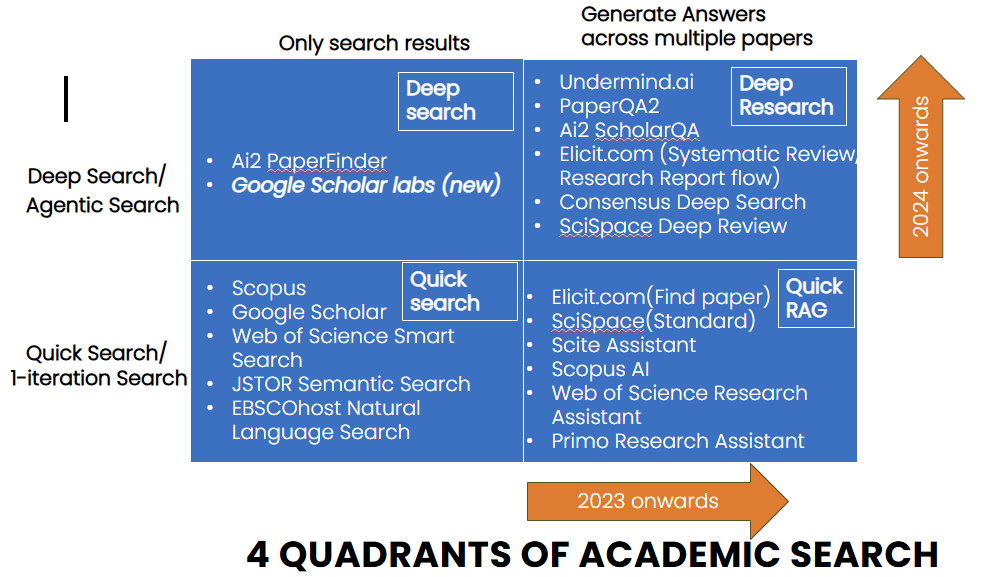

We now have four distinct quadrants of AI search tools:

Quick Search: Conventional single-shot search (lexical, semantic, or hybrid) showing ranked results. Examples: most traditional databases, Google Scholar.

Quick RAG: Single-shot retrieval plus short generated answer. Examples: early Elicit, Scite Assistant.

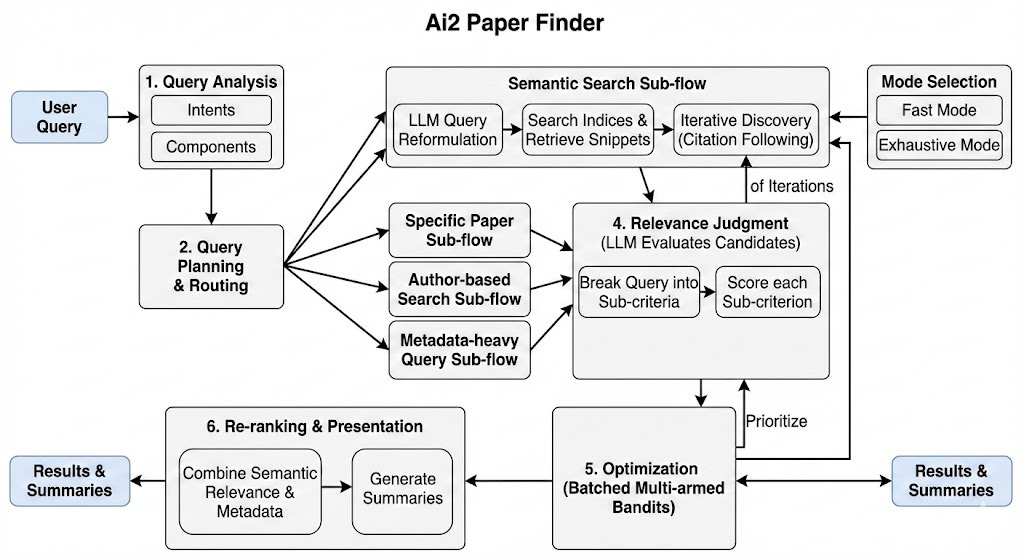

Deep Search: Iterative retrieval taking minutes, with LLM relevance ranking, returning ranked results. Examples: AI2 Paperfinder, Scholar Labs.

Deep Research: Deep Search plus report generation. Examples: Undermind, Elicit Reports, Consensus Deep Search.

But where does “agentic search” or agents that search fit? I’ve been implying that Deep (Re)search is synonymous with agentic search. Is this actually true?

While the definition of “agent” has been hotly debated in the AI industry. one technical definition gaining traction is simply to say

An LLM agent runs tools in a loop to achieve a goal.

or as defined by Anthropic - agents are

LLMs autonomously using tools in a loop

By the “LLM using tools in a loop” definition, virtually all Deep Search and Deep Research tools ARE agents—they use LLMs to make decisions, call tools (search APIs, citation networks), evaluate results, and iterate. AI2 Paperfinder, Elicit, Consensus Deep Search, Undermind—all qualify.

Case closed? Not quite.

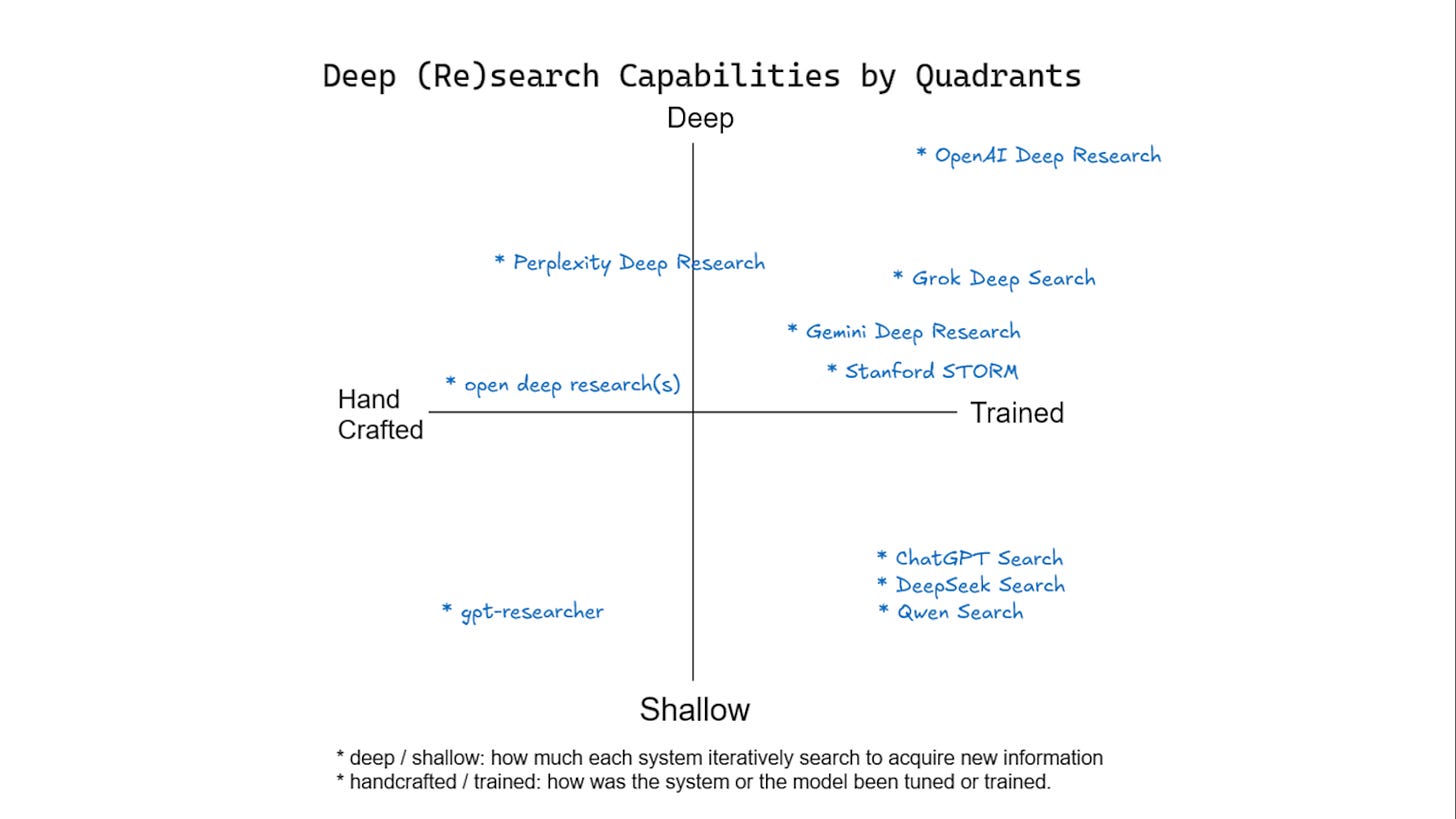

Autonomy or Agentic Behavior is a spectrum

Anthropic defines agents as LLMs autonomously using tools in a loop but there are different degrees of autonomy or agency that could be given to the LLMs.

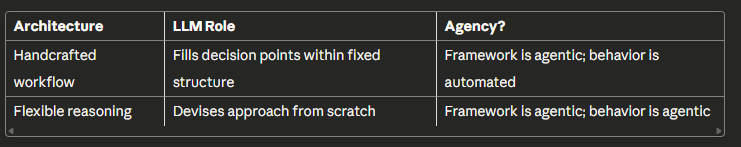

Imagine at one end of the spectrum we have

100% Handcrafted systems : These systems follow predetermined workflows. The LLM makes decisions at specific points, but the workflow structure is fixed by human designers. Think of it as a decision tree: sophisticated, yes, but anticipated in advance.

At the other end we have

100% Flexible systems: These systems reason from scratch about how to accomplish a task. Given a novel request, they devise an approach dynamically, combining available tools as needed to try to accomplish the goal.

Indeed one early analysis of Deep Research tools proposed this very distinction.

A clear example of a handcrafted system is Allen Institute for AI’s PaperFinder. They makes this explicit when describing their Paperfinder architecture as a “semi-rigid flow: a predefined structure that is influenced at key points by various LLM decisions.” They acknowledge: “Of course, it would be cool if the LLM component were more dynamic and allowed more autonomy in how it influences the flow.”

In comparison, tools like OpenAI Deep Research sit much closer to the trained / autonomous end of the spectrum than most academic “Deep Search” products.

Where a workflow-based tool like AI2 Paperfinder follows a predefined sequence (query analyser → router → sub-flow A/B/C, etc.), Deep Research behaves more like a general-purpose research agent:

It starts from a natural language prompt:

“Write a detailed literature review on X, highlighting key debates and gaps.”

It plans its own work: decomposes the task into subtasks (e.g., “define scope”, “gather sources”, “cluster perspectives”, “draft sections”).

It chooses tools dynamically: web search, citation lookups, summarisation, comparison, checking contradictions, etc.

It adjusts the plan on the fly if it hits coverage gaps, conflicting evidence, or poor sources.

Unlike LLMs that have fixed workflows, the same prompt can be handled very differently (e.g. might use different set of tools) due to the non-deterministic nature of LLMs

These types of systems tend to be trained with reinforcement learning

This spectrum of agency or autonomy captures something crucial. Most current academic Deep Search and Deep Research tools sit firmly on the handcrafted end: sophisticated workflows, yes, but workflows that human designers anticipated in advance. The LLM’s role is to make intelligent choices within the workflow—not to design the workflow itself.

Which means such tools will almost certainly fail when asked to do tasks that don’t fit neatly into those predetermined workflows. Worse, they may still return results—it may not even be obvious that the system has failed until you examine the output carefully.

Of course, one could argue The “LLM + tools in loop” definition is too permissive a defintion for agents or agentic behavior. Perhaps tools like AI2 Paperfinder are “agentic systems/frameworks” to automate certain tasks as opposed to being actual agents with agentic behavior. But there is no right definition!

Does the “agentic” or “research assistant” framing lead to misunderstandings?

Many of these AI literature review or AI powered tools have adopted marketing language, that may suggest advanced autonomous capabilities— by either talking about ”research agents” if not about “research assistants”.

I am not pointing fingers at particular players, pretty much all of them do similar marketing.

Consider these framings:

Scholar Agent is your personal research assistant in Consensus, built into Pro and Deep search modes. It goes beyond quick summaries by performing multi-step searches, applying rigorous academic filters, and surfacing deeper insights, trends, and key papers-fast.

Undermind.ai homepage is more restrained on their homepage but you see on their Y Combinator tagline they also invoke the “agent” idea

An AI agent for scientific research

Meanwhile, pretty much every tool even if it avoids the “Agentic” language - positions their tool as a “research assistant” (e.g. Elicit.com, Clarivate products).

This language—”research assistant,” “agent,” “multi-step reasoning”—implies flexibility. It suggests that given any literature review task, these systems can devise an approach, just as a human research assistant would.

But if the underlying architecture is handcrafted workflows, users will inevitably encounter tasks that fall outside those workflows—and be surprised when the system fails.

How autonomous or flexible is your agent?

Any AI search tool can find papers on a topic fitting some criteria. But can they handle this simple task?

Find me papers that could/should have been cited by Paper X but were not.

A human research assistant would immediately devise a plan:

Find papers on the same topic as X, filtered by publication year

Extract the references from Paper X

Report papers found in step 1 that don’t appear in step 2

This requires no specialized knowledge—just the ability to reason about task structure and combine tools appropriately (well within reach of the reasoning capabilities of modern LLMs). I also choose this task because many Academic Deep Research tools like Undermind.ai, Consensus Deep Search, all claim the ability to do citation searching.

It’s precisely the kind of task that reveals whether a system has flexible reasoning or merely executes handcrafted workflows.

We may expect that these LLM “agents” or “research assistants” when given a task to reason from scratch and “decide” what to do with the tools they have. Systems with fixed workflows will probably fail, unless the designers had anticipated such tasks and created a workflow in advance for this (unlikely).

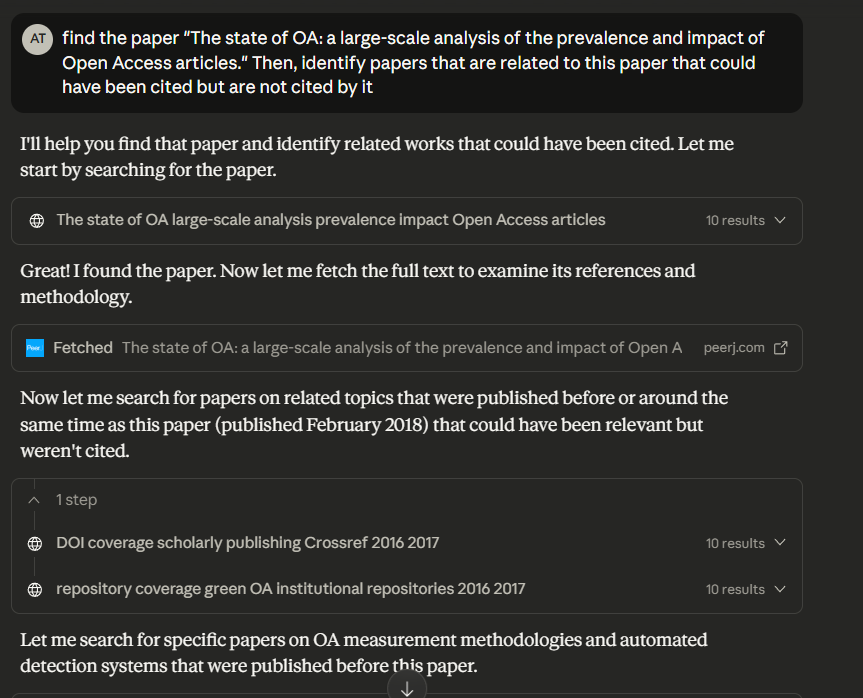

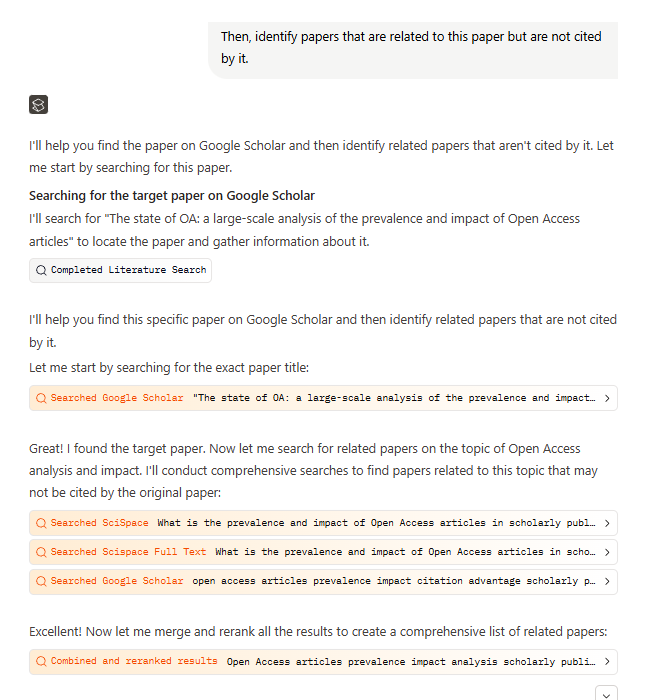

I tested this using an open access paper: “The state of OA: a large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles.” My prompt:

find the paper “The state of OA: a large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles.” Then, identify papers that are related to this paper that could have been cited but are not cited by it

The paper is open access, so failure wouldn’t result from access restrictions. It has a relatively comprehensive bibliography, so randomly suggesting papers wouldn’t work.

For the system to succeed, it needs to have the capability to access the paper, extract its references, find related papers, and compare and filter.

Most importantly, it needs either a predefined workflow for this specific task (unlikely) or the ability to reason flexibly about combining available tools.

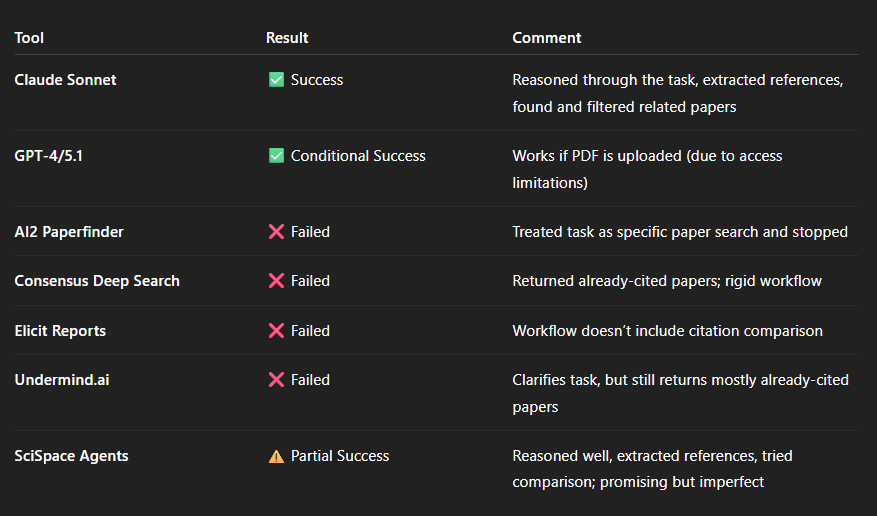

The Results

General-purpose LLMs succeeded. Claude Sonnet—even the free version with default web search—reasoned through the task structure, identified the paper, extracted references, found related work, and filtered appropriately.

Some suggestions were tangentially related (the obvious ones were already cited), but it clearly understood and executed the task logic. .

GPT models similarly succeeded when I tested them months ago.

Gemini and GPT-5.1 currently struggle, but primarily due to access issues (they claim to be blocked from full-text). Uploading the PDF directly works.

Notably, I used these LLMs in standard mode, not Deep Research mode. Deep Research modes should work as well unless they trigger predetermined workflows rather than flexible reasoning.

In conclusion, almost all top general-purpose LLMs sit on the trained/flexible end of the spectrum: they reason from scratch about each prompt and devise approaches dynamically.

Most Specialized Academic Deep Search/Research Tools Fail

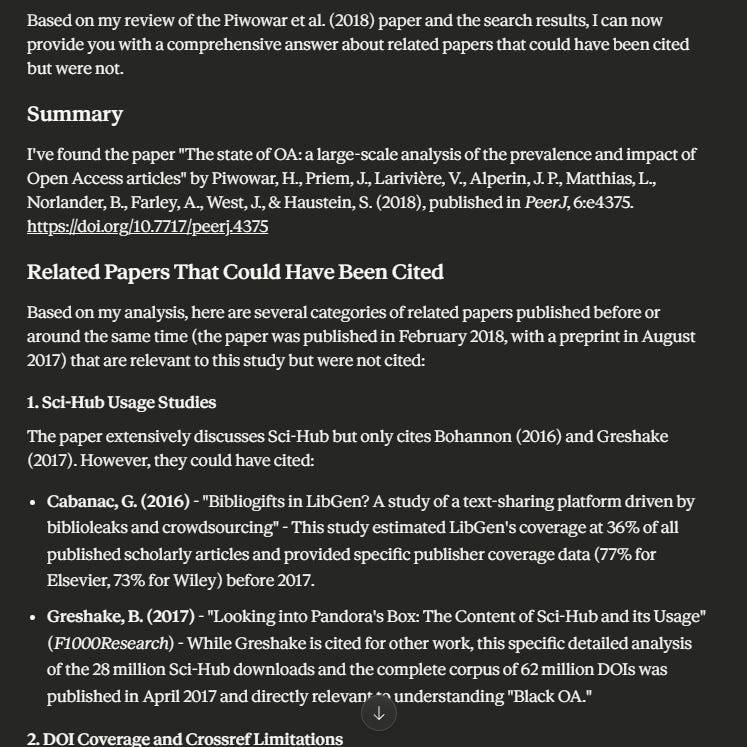

AI2 Paperfinder has a pretty transparent workflow in their blog post, so I asked Gemini 3 to extract the workflow and generate a flow diagram using Nano Banana Pro and this was the result.

While the diagram above may not be 100% correct, it gives you a big picture view of what is happening. Important to note is that AI2 Paperfinder tries to direct your input to one of several subflows including “specific paper search, semantic search with potential metadata constraints, pure-metadata queries, and queries that involve an author name.”

When given my query it naturally considered it as a simple specific paper lookup and stopped once it found the target article. It had no capability of going further.

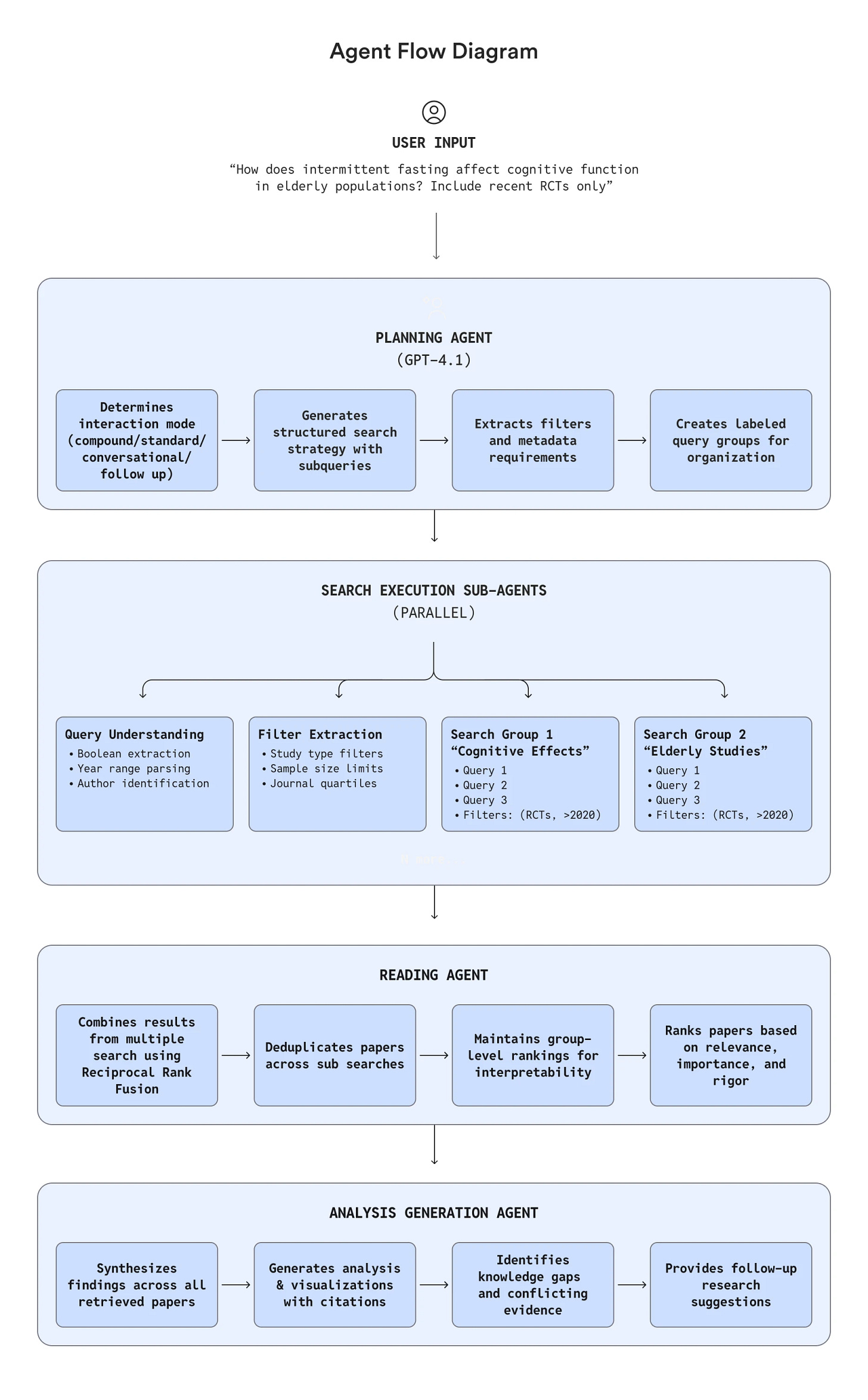

Consensus Deep Search also failed—despite using GPT5 to act as four different sub-agents (planning Agent, Search Agent, Reading Agent, Analysis Agent) and returned papers that were already cited.

In the end, it was designed for a fixed and specific workflow, as you can see from the user interface where it does the same steps no matter the query.

You get even more visibility of what is going on bu looking at the Agent Flow Diagram on OpenAI’s webpage! You can tell there is not much hope as it is using a pretty rigid structure.

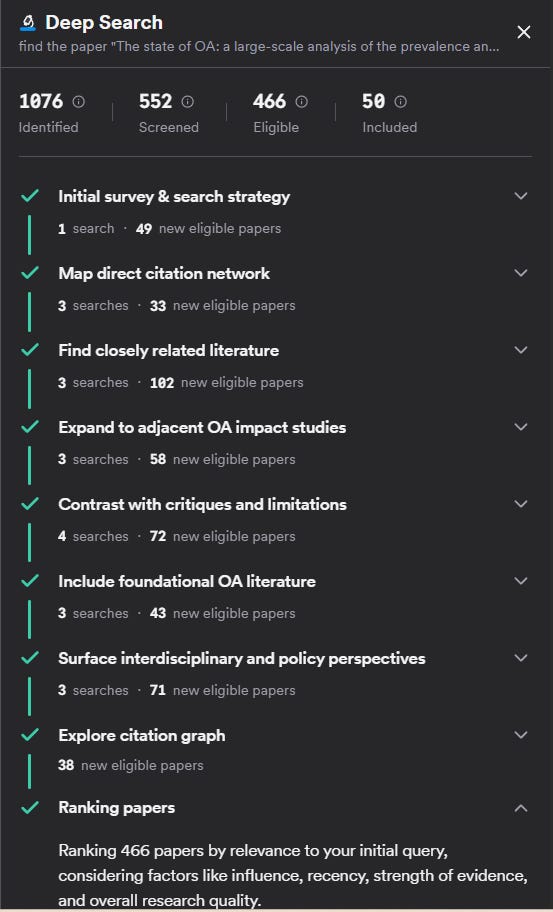

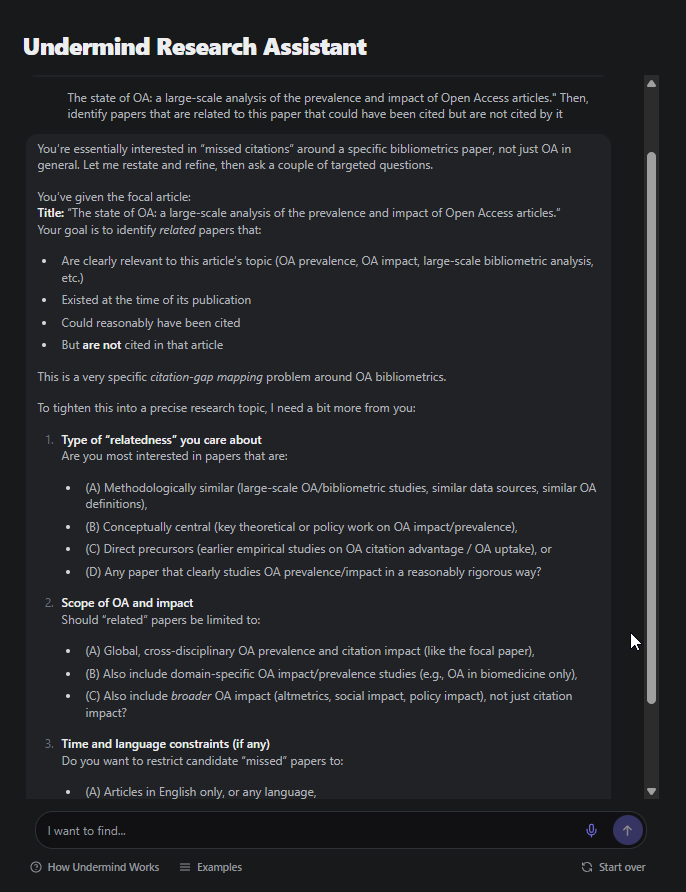

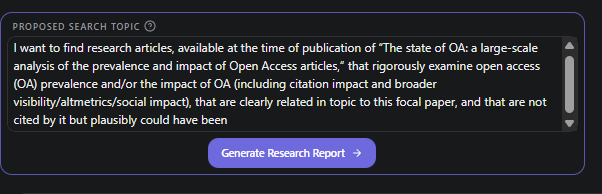

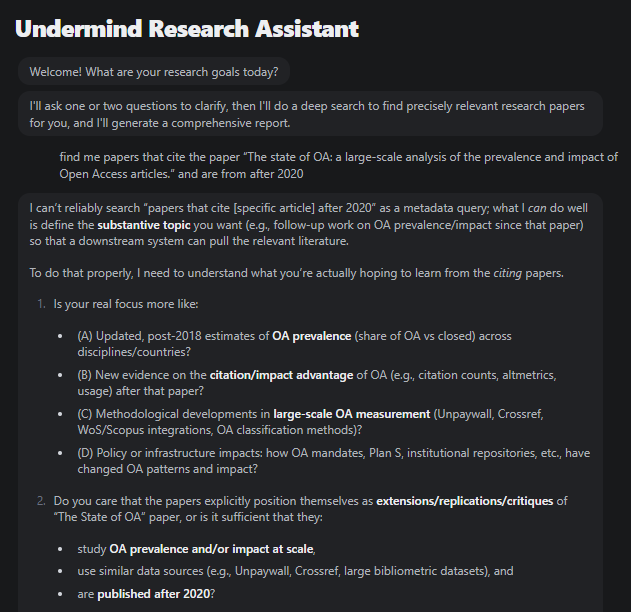

Undermind asked clarifying questions that seemed promising,

giving you the impression it could handle the request

It doesn’t work of course, it finds many related papers but most are cited already.

Because we have the least information about Undermind’s internals, I tried other tests e.g. Find me papers that cite or reference paper X but are before 2015, and here the LLM helps to clarify intent often warns you the system can not do the task you want!

Elicit Research Reports can’t succeed because its workflow is fixed: search → generate inclusion criteria → screen → extract. There’s no step for “check if paper is already cited in source document.”

In short, all of the Academic Deep Search and Deep Research failed because their “agents” are all working fixed defined flows and none of them had a flow predesigned for my task.

Why Handcrafted Workflows Aren’t Bad

While it seems like a more autonomous, more agentic system is clearly superior to one with handcrafted, pre-determined flows, it’s not as clear-cut as it looks.

Speed and efficiency: Fixed workflows are dramatically faster. Undermind and Consensus Deep Search complete comprehensive searches in 8-10 minutes. Flexible deep research tools like OpenAI’s Deep Research and Gemini Deep Research take 20-30 minutes for comparable tasks. When you know the workflow in advance, you can parallelize operations, pre-optimize queries, and avoid reasoning overhead.

Part of the reason why this difference is seen might also have to do with the different way these two classes of tools access data, with OpenAI/Gemini Deep Research tending to use slower more “real time” methods.

Reliability and consistency: Fixed workflows produce predictable outputs. Flexible reasoning introduces variance—sometimes brilliantly adaptive, sometimes nonsense attempts. For researchers needing dependable results, workflow constraints makes things more predictable.

Cost management: Open-ended agent loops are expensive. Each LLM call costs tokens; each API call costs money and time. Predefined workflows bound resource consumption predictably. A truly flexible agent might run dozens of exploratory attempts before settling on an approach.

Auditability: When Elicit or Consensus Deep Search follows a PRISMA-like workflow, researchers can evaluate methodology independently. Flexible reasoning is harder to audit—how do you assess whether an agent’s self-designed approach was appropriate?

For standard literature reviews, systematic reviews, and discovery searches, workflow-optimized tools are often the right choice. Why have an LLM reinvent the wheel for well-understood tasks?

My critique isn’t that predetermined fixed workflow are bad—it’s that marketing language suggesting flexible reasoning misrepresents or at least can mislead users to overestimate the capabilities of the system.

SciSpace Agents - does this break the mold

Are there specialised academic search tools that work like truly flexible agents the way Claude, ChatGPT and Gemini are and can handle and reason out arbitrary literature review tasks?

If there is anyone that might be able to do it, it would be the new SciSpace Agents.

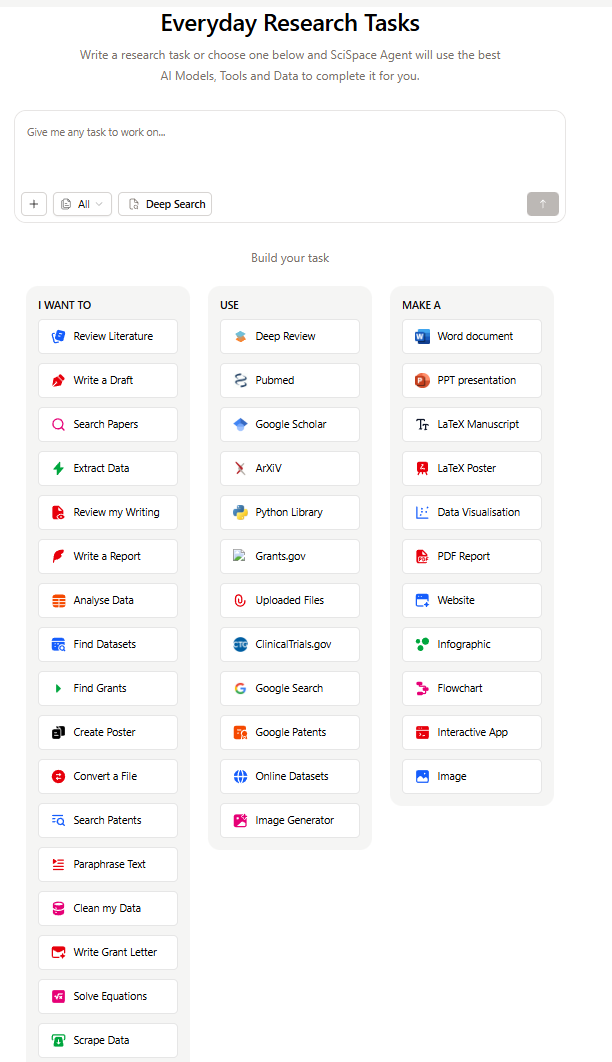

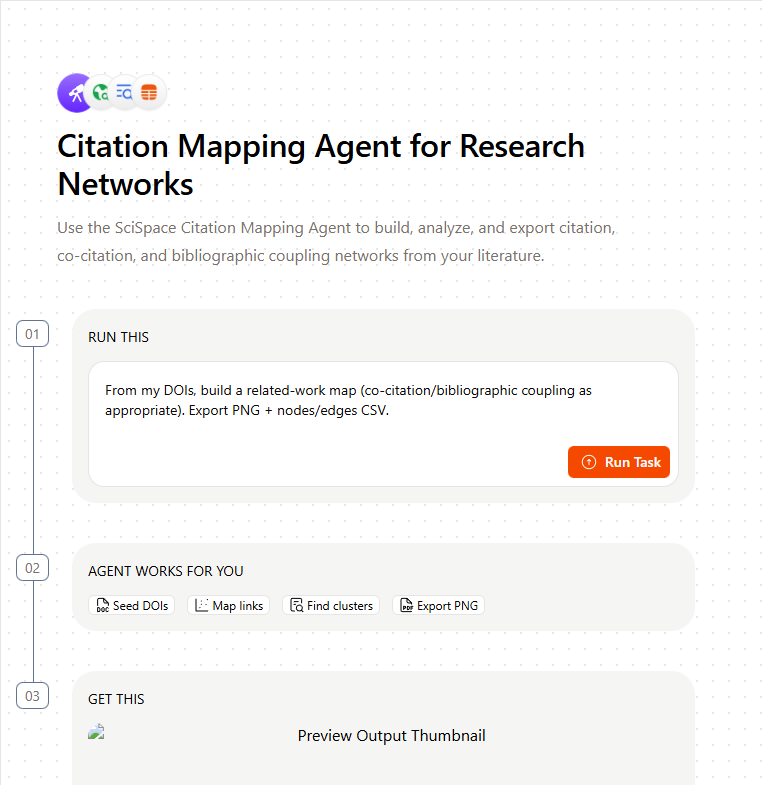

SciSpace Agents (distinct from SciSpace Deep Review) represents an interesting architectural alternative. Rather than encoding fixed workflows, it exposes a toolkit and lets the LLM reason about using different tool combination.

From what I can see SciSpace Agents exposes a bunch of tools that you can use to ask it to try to accomplish your tasks.

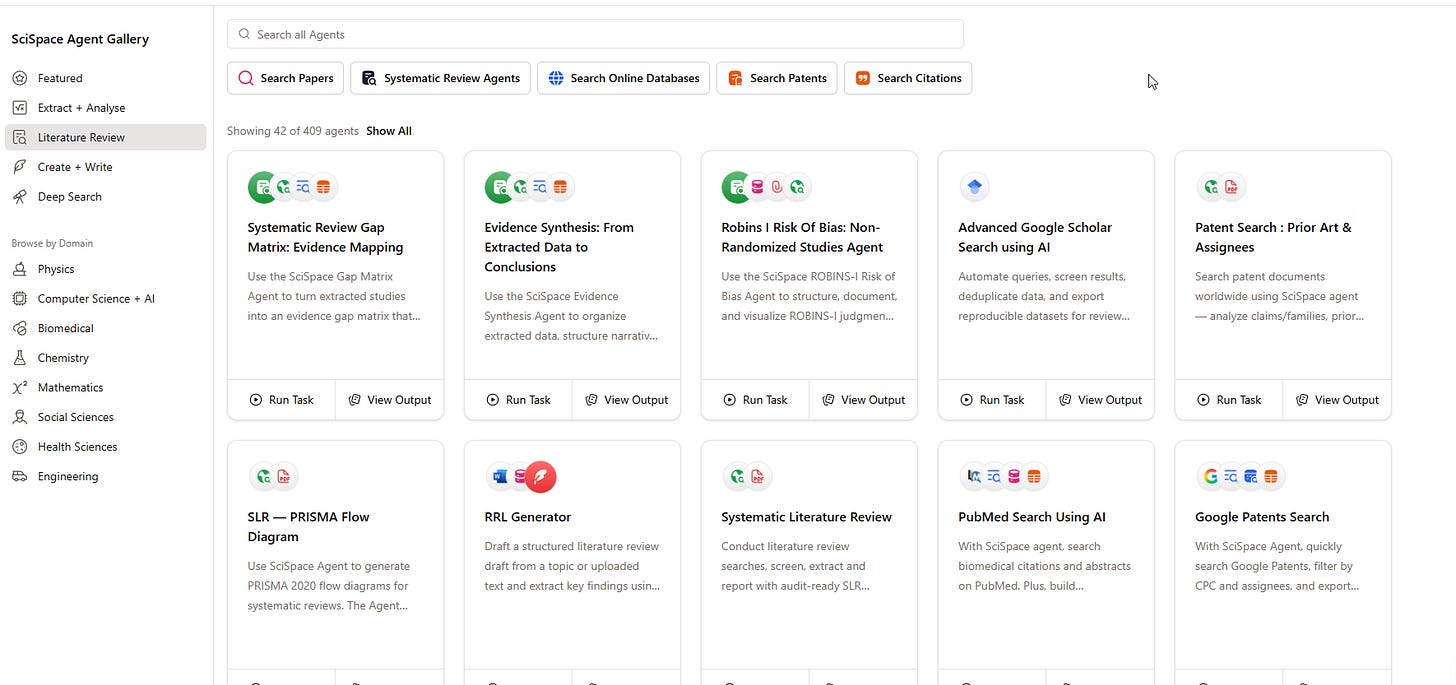

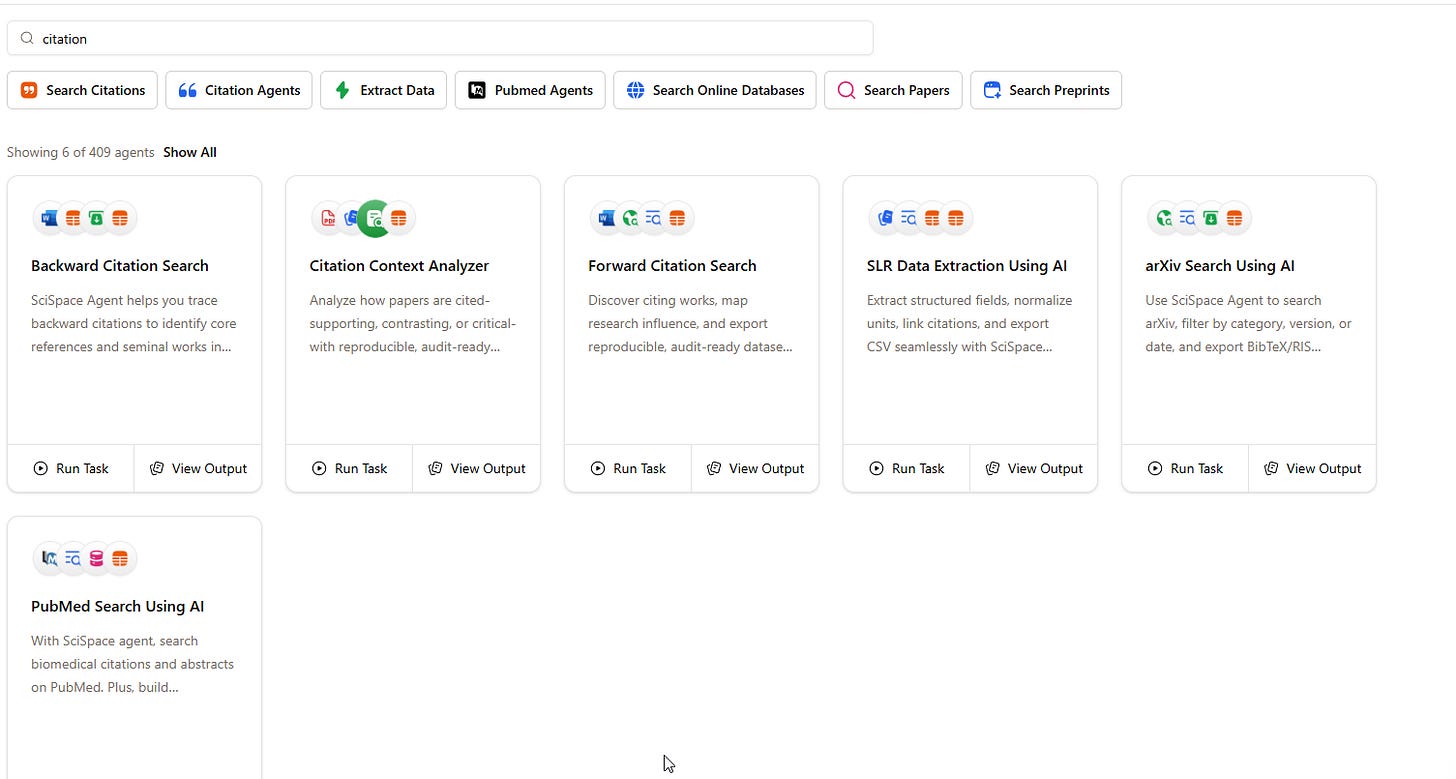

SciSpace Agents has an Agent Gallery that shows a wide variety of tasks that can be done with the tools with many relating to systematic review tasks, citation mapping, and various analytical workflows.

Users can inspect the exact flow for each agent.

SciSpace Agent is credit based (unlike SciSpace Deep Review), this gives you an idea of how expensive this process is.

So does it work? Sort of.

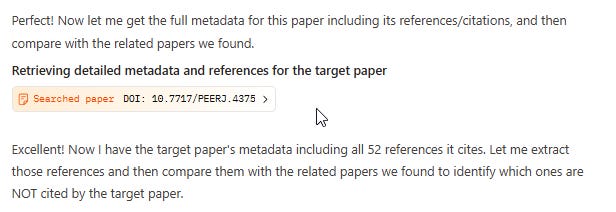

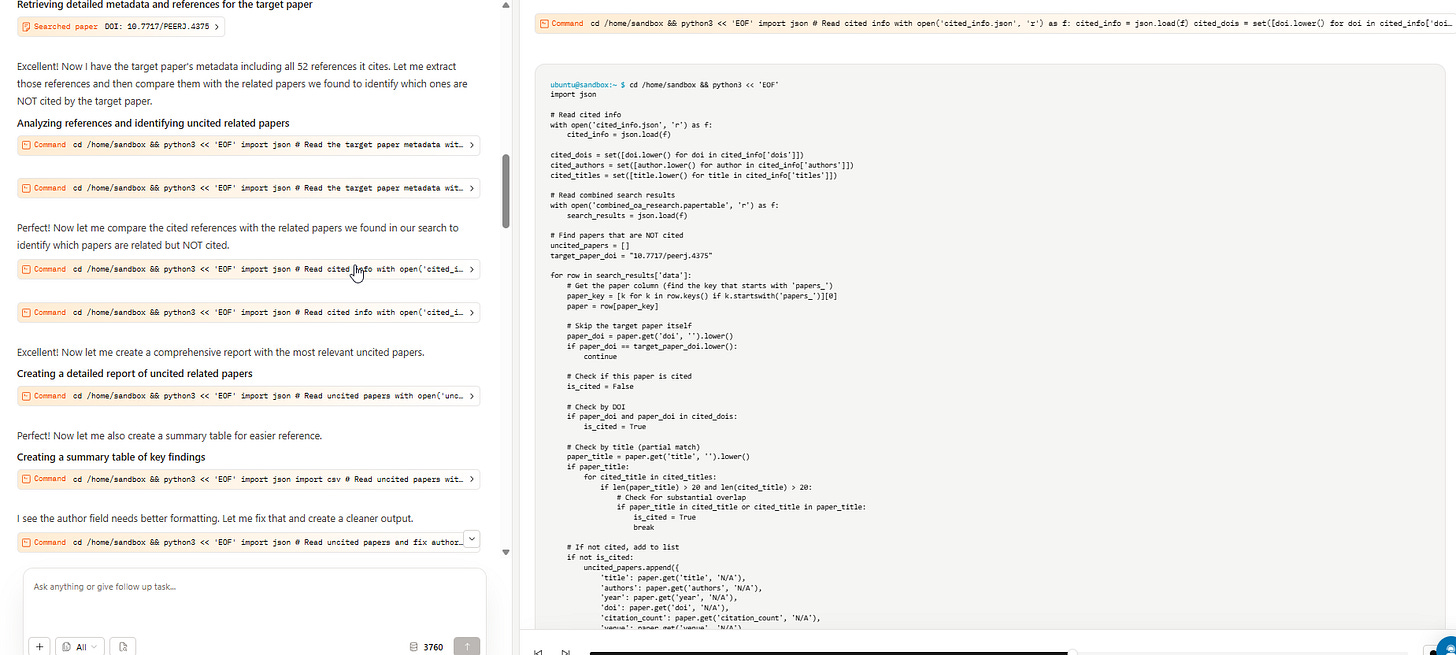

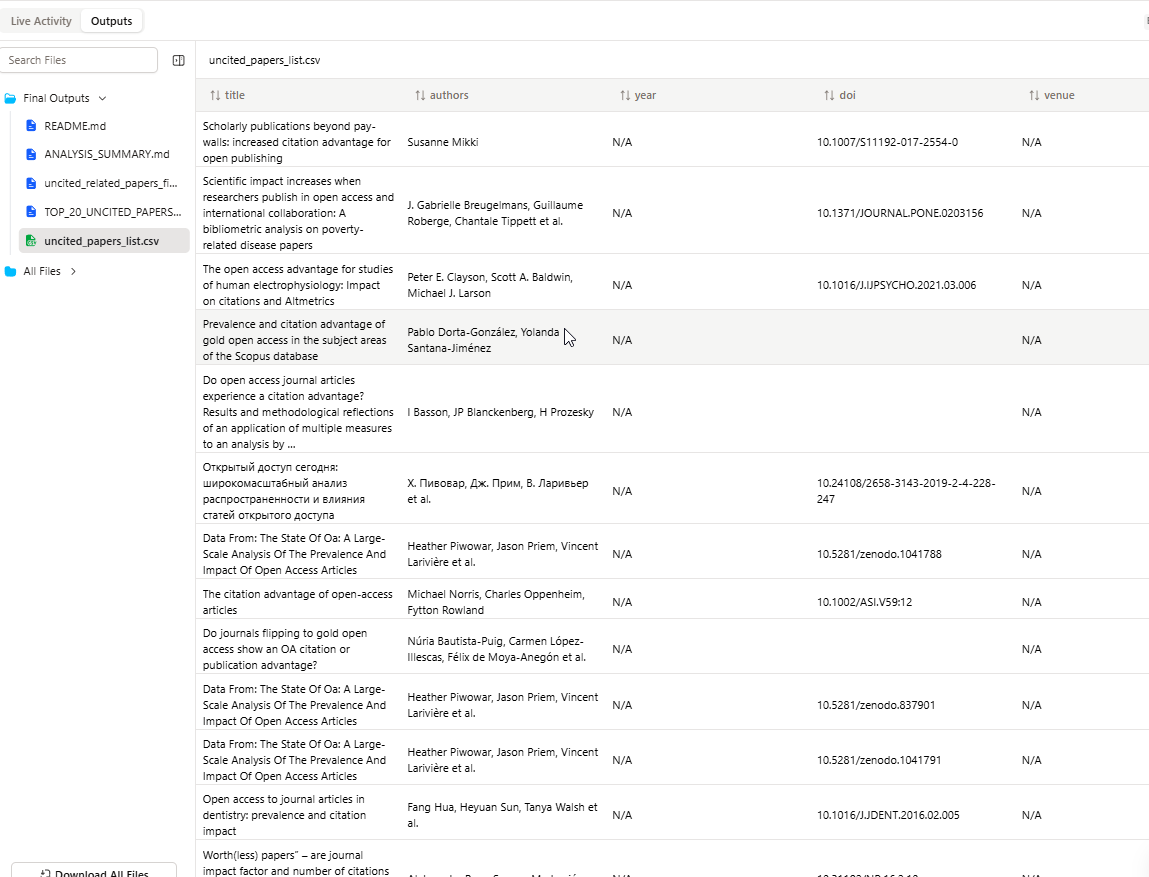

When I tried it, SciSpace Agents immediately behaved more like Claude/Gemini: it reasoned about what to do, identified the target paper, used various tools to find related work, extracted references into a JSON file with 52 entries, and attempted comparison, exactly as you would hope a agent or research assistant would do.

First, it identifies the target paper. Then it uses various tools such as Google Scholar, SciSpace Deep Review to find related papers, combines and dedupes

Here’s the critical part, it is able to use some tool to get the references of the paper in JSON.

I looked at the JSON it downloaded , it does indeed have the 52 references.

It then loads the JSON and tries to compare with the metadata of other papers found

I am not sure if it eventually succeeded but most of what it suggests are not cited (with a few exceptions where the matching failed due to incomplete metadata)

Conclusion

This simple citation gap test reveals that most current Academic Deep Search and Deep Research tools are workflow-based agents operating within predefined patterns—not flexible reasoning systems that analyze task structure and devise novel approaches.

This doesn’t diminish their value. Academic Deep Search’s iterative retrieval with LLM-based relevance judgment is a genuine breakthrough. Deep Research’s ability to generate well-cited reports fills real needs. These tools ARE agents in the technical sense, and within their designed scope, they work impressively.

But marketing language suggesting flexible reasoning, autonomous problem-solving, and human-like research assistance probably overstates current capabilities and can lead to misunderstanding by users who take the term “agent” or “research assistant” at face value.

Again Academic Deep Research tools are genuinely useful but you have to be careful with the type of literature review tasks you try to do. If your task fits the workflow, you’ll often get excellent results. If it doesn’t, you’ll may get a surprisingly fail.

The question that should be on our minds is - how do vendors of such products communicate to users the limits of their Deep Research product?

Brilliant dissection of the workflow vs reasoning divide. The citation gap test really exposes how these tools are pattern-matchers rather than flexible thinkers, something that matters alot when venturing outside predefined templates. The speed-reliability tradeoff is intresting too becuase for most standarized lit reviews, I'd probably take Undermind's 8-minute workflow over 30-minute open-ended reasoning anyway.